MULE CROSSING: Benefits of Postural Core Strength Training

By Meredith Hodges

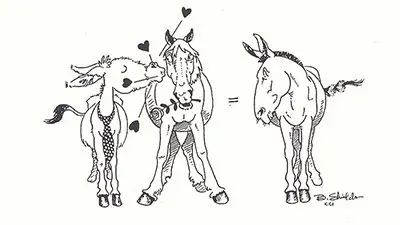

Most equines can be taught to carry a rider in a relatively short time. However, just because they are compliant doesn’t mean their body is adequately prepared for what they will be asked to do and that they are truly mentally engaged in your partnership. We can affect our equine’s manners and teach them to do certain movements and in most cases, we will get the response that we want…at least for the moment. Most of us grow up thinking that getting the animal to accept a rider is a reasonable goal and we are thrilled when they quickly comply. When I was first training equines, I even thought that to spare them the weight of the rider when they were younger and that it would be more beneficial to drive them first as this seemed less stressful for them. Of course, I was then unaware of the multitude of tiny details that were escaping my attention due to my limited education. I had a lot to learn.

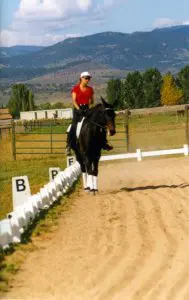

Because my equines reacted so well during training, I had no reason to believe that there was anything wrong with my approach until I began showing them. I started to experience resistant behaviors in my animals that I promptly attributed to simple disobedience. I had no reason to believe that I wasn’t being kind and patient until I met my dressage instructor, Melinda Weatherford. I soon learned that complaining about Sundowner’s negative response to his dressage lessons and blaming HIM was not going to yield any shortcuts to our success. The day she showed up with a big button on her lapel that said, “No Whining” was the end of my complaining and impatience, and the beginning of my becoming truly focused on the tasks at hand. I learned that riding through (and often repeating) mistakes did not pose any real solutions to our problems. I attended numerous clinics from all sorts of notable professionals and we improved slowly, but a lot of the problems were still present. Sundowner would still bolt and run when things got a bit awkward, but he eventually stopped bolting once I changed my attitude and approach, and when he was secure in his core strength in good equine posture.

Because my equines reacted so well during training, I had no reason to believe that there was anything wrong with my approach until I began showing them. I started to experience resistant behaviors in my animals that I promptly attributed to simple disobedience. I had no reason to believe that I wasn’t being kind and patient until I met my dressage instructor, Melinda Weatherford. I soon learned that complaining about Sundowner’s negative response to his dressage lessons and blaming HIM was not going to yield any shortcuts to our success. The day she showed up with a big button on her lapel that said, “No Whining” was the end of my complaining and impatience, and the beginning of my becoming truly focused on the tasks at hand. I learned that riding through (and often repeating) mistakes did not pose any real solutions to our problems. I attended numerous clinics from all sorts of notable professionals and we improved slowly, but a lot of the problems were still present. Sundowner would still bolt and run when things got a bit awkward, but he eventually stopped bolting once I changed my attitude and approach, and when he was secure in his core strength in good equine posture.

I thought about what my grandmother had told me years ago about being polite and considerate with everything I did. Good manners were everything to her and I thought I was using good manners. I soon found that good manners were not the only important element of communication. Empathy was another important consideration…to put oneself in the other “person’s” shoes, and that could be attributed to animals as well. So, I began to ask myself how it would feel to me if I was approached and treated the way I was treating my equines. My first epiphany was during grooming. It occurred to me that grooming tools, like a shedding blade, might not feel very  good unless I was careful about the way I used it. Body clipping was much more tolerable for them if I did the hard-to-get places first and saved the general body for last. Standing for long periods of time certainly did not yield a calm, compliant attitude when the more tedious places were left until last. After standing for an hour or more, the animal got antsy when I was trying to do more detailed work around the legs, head, flanks and ears after the body; so I changed the order. Generally speaking, I slowed my pace and eliminated any abrupt movements on my part to give the equine adequate time to assess what I would do next and approached each task very CAREFULLY. The results were amazing! I could now groom, clip bridle paths and fly spray everyone with no halters, even in their turnout areas as a herd. They were all beginning to really trust me.

good unless I was careful about the way I used it. Body clipping was much more tolerable for them if I did the hard-to-get places first and saved the general body for last. Standing for long periods of time certainly did not yield a calm, compliant attitude when the more tedious places were left until last. After standing for an hour or more, the animal got antsy when I was trying to do more detailed work around the legs, head, flanks and ears after the body; so I changed the order. Generally speaking, I slowed my pace and eliminated any abrupt movements on my part to give the equine adequate time to assess what I would do next and approached each task very CAREFULLY. The results were amazing! I could now groom, clip bridle paths and fly spray everyone with no halters, even in their turnout areas as a herd. They were all beginning to really trust me.

There was still one more thing my grandmother had said that echoed in my brain, “You are going to be a sorry old woman if you do not learn to stand up straight and move in good posture!” Good posture is not something that we are born with. It is something that must be learned and practiced repetitiously so that it becomes habitual for it to really contribute to your overall health. Good posture begins at the core, “the innermost, essential part of anything.” In a human being, it lies behind the belly button amongst the vital organs and surrounded by the skeletal frame. In a biped, upon signals from the brain, energy impulses run from the core and up from the waist, and simultaneously down through the lower body and  legs. The core of an equine is at the center of balance in the torso. Similar to bipeds, they need the energy to run freely along the hindquarters and down through the hind legs to create a solid foundation from which to allow the energy in front to rise into suspension to get the most efficient movement. When their weight is shifted too much onto the front end, their ability to carry a rider efficiently and correctly is compromised. To achieve correct energy flow and efficient movement, the animal’s internal supportive structures need to be conditioned in a symmetrical way around the skeletal frame. People can do this by learning to walk with a book on their head and with Pilates exercises, but how can we affect this same kind of conditioning in a quadruped?

legs. The core of an equine is at the center of balance in the torso. Similar to bipeds, they need the energy to run freely along the hindquarters and down through the hind legs to create a solid foundation from which to allow the energy in front to rise into suspension to get the most efficient movement. When their weight is shifted too much onto the front end, their ability to carry a rider efficiently and correctly is compromised. To achieve correct energy flow and efficient movement, the animal’s internal supportive structures need to be conditioned in a symmetrical way around the skeletal frame. People can do this by learning to walk with a book on their head and with Pilates exercises, but how can we affect this same kind of conditioning in a quadruped?

The first issue I noticed was with leading our animals. When we lead our animals with the lead rope in the right hand, we drop our shoulder and are no longer in good posture. When we walk, our hand moves ever so slightly from left to right as we walk; we inadvertently move the equine’s head back and forth. They balance with their head and neck. Thus, we are forcing them off balance with every step that we take. Since movement builds muscle, they are being asymmetrically conditioned internally and externally with every step we take together. In order to correct this, we must allow the animal to be totally in control of his own body as we walk together. We are cultivating proprioception or “body awareness.”

During the time you do the core strength leading exercises, you should NOT ride the animal as this will inhibit the success of these preliminary exercises. It will not result in the same symmetrical muscle conditioning, habitual behavior and new way of moving. For the best results, lessons need to be routine and done in good posture from the time you take your equine from the pen until the time you put him away. Hold the lead rope in your LEFT hand, keeping slack in the lead rope. Keep his head at your shoulder, match your steps with his front legs, point in the direction of travel with your right hand and look where you are going. Carry his reward of oats in a fanny pack around your waist; he’s not likely to bolt if he knows his reward is right there in the fanny pack.

Plan to move in straight lines and do gradual turns that encourage him to stay erect and bend through his rib cage, keeping an even distribution of weight through all four feet. Square him up with equal weight over all four feet EVERY TIME you stop and reward him with oats from your fanny pack. Then wait patiently for him to finish chewing. We are building NEW habits in the equine’s way of moving and the only way that can change is through routine, consistency in  the routine and correctness in the execution of the exercises. Since this requires that you be in good posture as well, you will also reap the benefits from this regimen. Along with feeding correctly (explained on my website at www.luckythreeranch.com), these exercises will help equines to drop fat rolls and begin to develop the top line and abdominal strength in good posture. The spine will then be adequately supported to easily accept a rider. He will be better able to stand still as you pull on the saddle horn to mount.

the routine and correctness in the execution of the exercises. Since this requires that you be in good posture as well, you will also reap the benefits from this regimen. Along with feeding correctly (explained on my website at www.luckythreeranch.com), these exercises will help equines to drop fat rolls and begin to develop the top line and abdominal strength in good posture. The spine will then be adequately supported to easily accept a rider. He will be better able to stand still as you pull on the saddle horn to mount.

When the body is in good posture, all internal organs can function properly and the skeletal frame will be supported correctly throughout his entire body. This will greatly minimize joint problems, arthritis and other anomalies that come from asymmetrical development and compromises in the body. Just as our children need routine, ongoing learning and the right kind of exercise while they are growing up, so do equines. They need boundaries for their behavior clearly outlined to minimize anxious behaviors and inappropriate behavior. The exercises that you do together need to build strength and coordination in good equine posture. The time spent together during leading training and going forward, slowly builds a good solid relationship with your equine and fosters his confidence and trust in you. He will know it is you who actually helps him to feel physically much better than he ever has.

Core muscle strength and balance must be done through correct leading exercises on flat ground. Coordination can be added to his overall carriage with the addition of negotiating obstacles on the lead rope done the same way. Once familiar with the obstacles, you will need to break them down into very small segments where the equine is asked to randomly halt squarely every couple of steps through the obstacle. You can tell when you have successfully achieved core strength in good balance, when your equine will perform accurately with the lead rope slung over his neck. He will stay at your shoulder, respond to hand signals and body language only and does what is expected perfectly. A carefully planned routine coupled with an appropriate feeding program is critical to your equine’s healthy development.

The task at the leading stage is not only to teach them to follow, but to have your equine follow with his head at your shoulder as you define straight lines and gradual arcs that will condition his body symmetrically on all sides of the skeletal frame. This planned course of action also begins to develop a secure bond between you. Mirror the steps of his front legs as you go through the all movements keeping your own body erect and in good posture. Always look in the direction of travel and ask him to square up with equal weight over all four feet every time he stops and reward him. This kind of leading training develops strength and balance in the equine body at the deepest level so strengthened muscles will hold the bones, tendons, ligaments and even cartilage in correct alignment. Equines that are not in correct equine posture will have issues involving organs, joints, hooves and soft tissue trauma. This is why it is so important to spend plenty of time perfecting your techniques every time you lead your equine.

The task at the leading stage is not only to teach them to follow, but to have your equine follow with his head at your shoulder as you define straight lines and gradual arcs that will condition his body symmetrically on all sides of the skeletal frame. This planned course of action also begins to develop a secure bond between you. Mirror the steps of his front legs as you go through the all movements keeping your own body erect and in good posture. Always look in the direction of travel and ask him to square up with equal weight over all four feet every time he stops and reward him. This kind of leading training develops strength and balance in the equine body at the deepest level so strengthened muscles will hold the bones, tendons, ligaments and even cartilage in correct alignment. Equines that are not in correct equine posture will have issues involving organs, joints, hooves and soft tissue trauma. This is why it is so important to spend plenty of time perfecting your techniques every time you lead your equine.

The equine then needs to build muscle so he can sustain his balance on the circle without the rider before he will be able to balance with a rider. An equine that has not had time in the round pen to establish strength, coordination and balance on the circle, with the help of our postural restraint called the “Elbow Pull,” will have difficulty as he will be pulled off balance with even the slightest pressure. He will most likely raise his head, hollow his back and lean like a motorcycle into the turns. When first introduced to the “Elbow Pull,” his first lesson in the round pen should only be done at the walk to teach him to give to its pressure, arch his back and stretch his spine while tightening his abs. If you ask for trot and he resists against the “Elbow Pull,” just go back to the walk until he can consistently sustain this good posture while the “Elbow Pull” stays loose. He can gain speed and difficulty as his proficiency increases.

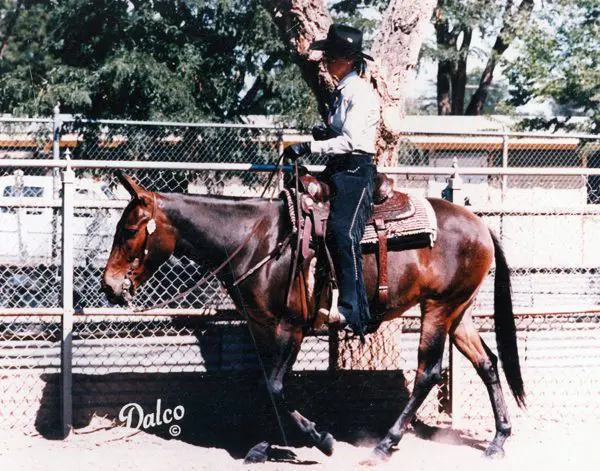

Loss of balance will cause stress, and even panic that can result in him pulling the lead rope, lunge line or reins under saddle right out of your hands and running off. This is not disobedience, just fear from a loss of balance and it should not be punished, just ignored and then calmly go back to work. The animal that has had core strength built through leading exercises, lunging on the circle and ground driving in the “Elbow Pull” before riding, will not exhibit these seemingly disobedient behaviors. Lunging will begin to develop hard muscle over the core muscles and internal supportive structures you have spent so many months strengthening during leading training exercises. It will further enhance your equine’s ability to perform and stay balanced in action, and play patterns in turnout will begin to change dramatically as this becomes his habitual way of going. Be sure to be consistent with verbal commands during all these beginning stages as they set the stage for better communication and exceptional performance later. Although you need to spend more time in his beginning training than you might want to, this will also add to your equine’s longevity and use-life by as much as 5-10 years. The equine athlete that has a foundation of core strength in good equine posture, whether used for pleasure or show, will be a much more capable and safe performer than one that has not, and he will always be grateful to YOU for his comfort.

Loss of balance will cause stress, and even panic that can result in him pulling the lead rope, lunge line or reins under saddle right out of your hands and running off. This is not disobedience, just fear from a loss of balance and it should not be punished, just ignored and then calmly go back to work. The animal that has had core strength built through leading exercises, lunging on the circle and ground driving in the “Elbow Pull” before riding, will not exhibit these seemingly disobedient behaviors. Lunging will begin to develop hard muscle over the core muscles and internal supportive structures you have spent so many months strengthening during leading training exercises. It will further enhance your equine’s ability to perform and stay balanced in action, and play patterns in turnout will begin to change dramatically as this becomes his habitual way of going. Be sure to be consistent with verbal commands during all these beginning stages as they set the stage for better communication and exceptional performance later. Although you need to spend more time in his beginning training than you might want to, this will also add to your equine’s longevity and use-life by as much as 5-10 years. The equine athlete that has a foundation of core strength in good equine posture, whether used for pleasure or show, will be a much more capable and safe performer than one that has not, and he will always be grateful to YOU for his comfort.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE and EQUUS REVISITED at www.luckythreeranchstore.com

© 2018, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

In my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the SPECIAL FEATURES of my EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), I talk about using a postural aid called the “Elbow Pull.” In the EQUUS REVISITED DVD, we teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. If you have our video series, in DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), we talk about using the “Elbow Pull.” We teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. The “Elbow Pull” puts your animal into your equine’s ideal posture. He will have full range of motion in every direction when it is adjusted correctly. He will just not be able to raise his head so high that he hollows his neck and back.

In my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the SPECIAL FEATURES of my EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), I talk about using a postural aid called the “Elbow Pull.” In the EQUUS REVISITED DVD, we teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. If you have our video series, in DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), we talk about using the “Elbow Pull.” We teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. The “Elbow Pull” puts your animal into your equine’s ideal posture. He will have full range of motion in every direction when it is adjusted correctly. He will just not be able to raise his head so high that he hollows his neck and back. underneath his body. The elevation (or suspension) in the shoulders allows him to increase the “reach” in his front legs. I use the “Elbow Pull” for Leading Training, Ground Driving and when he is ready, Lunging in the Round Pen. The Leading Training on flat ground through our HOURGLASS PATTERN positively affects his overall postural balance, and Leading through Obstacles adds coordination. You know that he is ready to go on to each stage of Leading Training on flat ground (and then through obstacles) when you can throw the lead rope over his neck and do the exercises with verbal commands, hand signals and body language alone. This is building a new habitual way of traveling is all in preparation for Lunging correctly…keeping his body erect and in a symmetrical balance while he bends to the arc of the circle through his torso without leaning like a motorcycle. It will prevent muscle compromises throughout his body that could cause soreness and compromise organ function.

underneath his body. The elevation (or suspension) in the shoulders allows him to increase the “reach” in his front legs. I use the “Elbow Pull” for Leading Training, Ground Driving and when he is ready, Lunging in the Round Pen. The Leading Training on flat ground through our HOURGLASS PATTERN positively affects his overall postural balance, and Leading through Obstacles adds coordination. You know that he is ready to go on to each stage of Leading Training on flat ground (and then through obstacles) when you can throw the lead rope over his neck and do the exercises with verbal commands, hand signals and body language alone. This is building a new habitual way of traveling is all in preparation for Lunging correctly…keeping his body erect and in a symmetrical balance while he bends to the arc of the circle through his torso without leaning like a motorcycle. It will prevent muscle compromises throughout his body that could cause soreness and compromise organ function. None of us were born in good posture. It is something that must be taught. If we are allowed to “slouch” in our posture, it WILL create soreness and physical problems over time, especially when we get much older. After Lunging in good posture for several months, the equine’s habitual way of going will be changed. He will begin to travel in good posture automatically.

None of us were born in good posture. It is something that must be taught. If we are allowed to “slouch” in our posture, it WILL create soreness and physical problems over time, especially when we get much older. After Lunging in good posture for several months, the equine’s habitual way of going will be changed. He will begin to travel in good posture automatically. their legs and not their backs. These kinds of exercises make sure that the animal travels symmetrically, allowing the joints to work as they were designed to do (according to the laws of physics) with no compromises, and promotes optimum function of their internal organs.

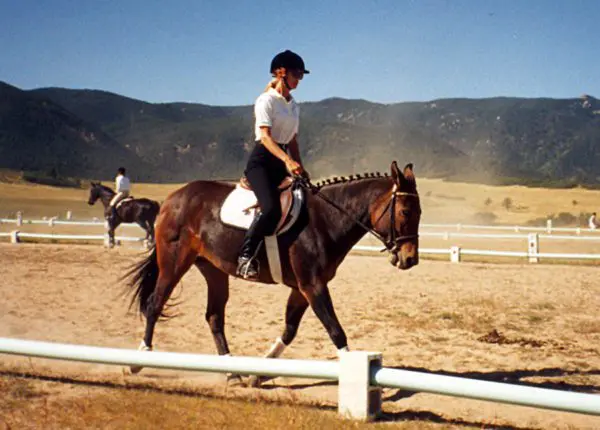

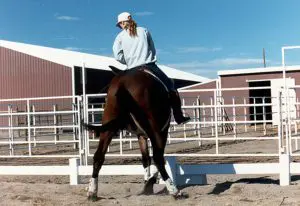

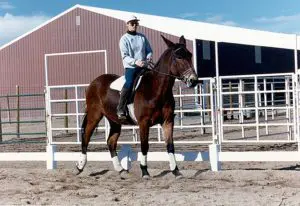

their legs and not their backs. These kinds of exercises make sure that the animal travels symmetrically, allowing the joints to work as they were designed to do (according to the laws of physics) with no compromises, and promotes optimum function of their internal organs. Lunge the equine in the Round Pen for several months until the animal habitually exhibits an erect posture with equal weight over all four feet and balanced self-body carriage. When you finally begin riding, you should use the “Elbow Pull” while you are riding our Hourglass Pattern under saddle as he adjusts to the added weight and new balance. When the “Elbow Pull” is adjusted correctly and the equine is in good posture, it will not put any pressure on the animal at all. When he is out of good posture, it puts pressure on the poll, the bit rings, behind the forearms and over the back. He will go back to his good posture as soon as he is able in order to release the pressure points.

Lunge the equine in the Round Pen for several months until the animal habitually exhibits an erect posture with equal weight over all four feet and balanced self-body carriage. When you finally begin riding, you should use the “Elbow Pull” while you are riding our Hourglass Pattern under saddle as he adjusts to the added weight and new balance. When the “Elbow Pull” is adjusted correctly and the equine is in good posture, it will not put any pressure on the animal at all. When he is out of good posture, it puts pressure on the poll, the bit rings, behind the forearms and over the back. He will go back to his good posture as soon as he is able in order to release the pressure points. Place the “Elbow Pull” over the poll, through the snaffle bit rings, between the animal’s front legs and over the back, then snap the two ends to a surcingle D-ring or D-rings, on the saddle you are using. It should be adjusted so he can only raise his head approximately 3-4 inches above the level of the withers (just before he hollows his neck and back). The “Elbow Pull” needs to be adjusted loosely enough so that he can relieve the pressure at the poll, bit rings, elbows and back without having to drop his head below the withers.

Place the “Elbow Pull” over the poll, through the snaffle bit rings, between the animal’s front legs and over the back, then snap the two ends to a surcingle D-ring or D-rings, on the saddle you are using. It should be adjusted so he can only raise his head approximately 3-4 inches above the level of the withers (just before he hollows his neck and back). The “Elbow Pull” needs to be adjusted loosely enough so that he can relieve the pressure at the poll, bit rings, elbows and back without having to drop his head below the withers. In the Round Pen, the “Elbow Pull” helps the animal learn to travel in good equine posture without the added weight of a rider first. In doing so, it increases his core strength and the ability for him to carry a more balanced posture of his own volition. The added weight of the rider under saddle will challenge the animal again to maintain this good posture. This will take further strengthening of the muscles. The “Elbow Pull” will keep the animal in the correct posture while carrying the rider, so he doesn’t ever build muscle out of balance and out of good equine posture. When you do this, you are changing old habitual movement into good equine posture and a balanced way of moving. This eventually (after two years) will become his habitual way of moving and playing, even during turnout.

In the Round Pen, the “Elbow Pull” helps the animal learn to travel in good equine posture without the added weight of a rider first. In doing so, it increases his core strength and the ability for him to carry a more balanced posture of his own volition. The added weight of the rider under saddle will challenge the animal again to maintain this good posture. This will take further strengthening of the muscles. The “Elbow Pull” will keep the animal in the correct posture while carrying the rider, so he doesn’t ever build muscle out of balance and out of good equine posture. When you do this, you are changing old habitual movement into good equine posture and a balanced way of moving. This eventually (after two years) will become his habitual way of moving and playing, even during turnout. If you are consistent during his lessons, being in good equine posture will become his normal way of going and will not disappear when you finally ride without it.

If you are consistent during his lessons, being in good equine posture will become his normal way of going and will not disappear when you finally ride without it. and to prevent the rider from injuring their spine (according to the laws of Physics). The “Elbow Pull” provides support much like a balance bar does for a beginning ballet dancer, and the principles of good posture are the same as with humans.

and to prevent the rider from injuring their spine (according to the laws of Physics). The “Elbow Pull” provides support much like a balance bar does for a beginning ballet dancer, and the principles of good posture are the same as with humans. you will need to cross the rope across their back, pull it taut into the correct tension and then secure the snaps, keeping plenty of slack in the rope. You want the rope semi-knot to slip if they brace against it, but you do not want loose snaps on the ends of the rope to swing free to hit the horse anywhere on his body. With horses, you would just twist the rope over the back as shown in the photo, so the snaps are a moot point until the horse learns to give to the Elbow Pull and can be hard tied.

you will need to cross the rope across their back, pull it taut into the correct tension and then secure the snaps, keeping plenty of slack in the rope. You want the rope semi-knot to slip if they brace against it, but you do not want loose snaps on the ends of the rope to swing free to hit the horse anywhere on his body. With horses, you would just twist the rope over the back as shown in the photo, so the snaps are a moot point until the horse learns to give to the Elbow Pull and can be hard tied. Although the “Elbow Pull” is a very simple and straight forward aid to help keep your equine in good posture, it is also a device that needs to be custom made to fit each individual equine. Equines that approximate the same size in the front quarters will probably be able to use the same one. First, you need to obtain a package of 3/8″ X 50′ nylon and polyester twisted rope. This is the way it is sold. Do not substitute any other kind of rope, or leather reins, etc. as this will have a different weight and slippage around the bridle and will not have the same effect.

Although the “Elbow Pull” is a very simple and straight forward aid to help keep your equine in good posture, it is also a device that needs to be custom made to fit each individual equine. Equines that approximate the same size in the front quarters will probably be able to use the same one. First, you need to obtain a package of 3/8″ X 50′ nylon and polyester twisted rope. This is the way it is sold. Do not substitute any other kind of rope, or leather reins, etc. as this will have a different weight and slippage around the bridle and will not have the same effect. You will also need two snaps that are narrow, yet fairly strong that can fit easily through the D-rings on your surcingle, or Western saddle. English saddle D-rings are generally too small and in this situation, we do not attach to them, but rather attach the “Elbow Pull” to itself over the top of the spine. If the rope tends to twist and the snaps slide off to the side, you can often just snap one snap to the D-ring and the other snap snapped to the first snap, or if the “Elbow Pull” is a bit shorter, you can just snap it to the small D-ring on each side. The reason for twisted rope is so you can actually go through the D-rings and snap it into the twisted rope itself for a more exact setting. You would just untwist the rope at the setting point and snap into the middle of the rope so it won’t slide.

You will also need two snaps that are narrow, yet fairly strong that can fit easily through the D-rings on your surcingle, or Western saddle. English saddle D-rings are generally too small and in this situation, we do not attach to them, but rather attach the “Elbow Pull” to itself over the top of the spine. If the rope tends to twist and the snaps slide off to the side, you can often just snap one snap to the D-ring and the other snap snapped to the first snap, or if the “Elbow Pull” is a bit shorter, you can just snap it to the small D-ring on each side. The reason for twisted rope is so you can actually go through the D-rings and snap it into the twisted rope itself for a more exact setting. You would just untwist the rope at the setting point and snap into the middle of the rope so it won’t slide. Have the equine stand at the hitch rail with the snaffle bridle on. To get a measurement for how long a piece of rope you will need for his “Elbow Pull,” take a length of rope from the coil. Feed the end of the rope from the inside to the outside of the snaffle bit ring, drape it over the poll of your equine and feed it from the outside of the snaffle bit ring to the inside on the opposite side of your equine. Then pull enough slack to go down through the front legs, behind the forearm, up and over the back such that it hangs one foot, or more (but not less) on the other side of the spine. Then, go back to the side on which you started and do the same on that side with the remainder of the 50″ foot length of rope and cut the rope at the 1-foot mark on the other side of the spine.

Have the equine stand at the hitch rail with the snaffle bridle on. To get a measurement for how long a piece of rope you will need for his “Elbow Pull,” take a length of rope from the coil. Feed the end of the rope from the inside to the outside of the snaffle bit ring, drape it over the poll of your equine and feed it from the outside of the snaffle bit ring to the inside on the opposite side of your equine. Then pull enough slack to go down through the front legs, behind the forearm, up and over the back such that it hangs one foot, or more (but not less) on the other side of the spine. Then, go back to the side on which you started and do the same on that side with the remainder of the 50″ foot length of rope and cut the rope at the 1-foot mark on the other side of the spine. Once you have the proper length of rope for your equine, you will need to unravel 3” – 4″ of one end of the rope and loop it through the ring on your first snap. Then you will braid the rope back into itself. First, pick the loose strand that is on top as you lay the rope across your hand, bend it around the end of the snap and feed it under a twist of the rope such that it creates a loop around the end of your snap and pull it snug. Then take the next loose strand (which would be the middle of the three strands) and feed it under the next twist down from the one you just did. Then do the same with the third loose strand under the third twist in the rope. Take all three strands in your hand, hold the rope so it doesn’t twist and pull all three strands snug. They should all line up.

Once you have the proper length of rope for your equine, you will need to unravel 3” – 4″ of one end of the rope and loop it through the ring on your first snap. Then you will braid the rope back into itself. First, pick the loose strand that is on top as you lay the rope across your hand, bend it around the end of the snap and feed it under a twist of the rope such that it creates a loop around the end of your snap and pull it snug. Then take the next loose strand (which would be the middle of the three strands) and feed it under the next twist down from the one you just did. Then do the same with the third loose strand under the third twist in the rope. Take all three strands in your hand, hold the rope so it doesn’t twist and pull all three strands snug. They should all line up. Next, turn the rope over so you can see where the angled lines of the twisted rope begins again and feed the first strand under the first twist, the second under the second twist and the third under the third twist. Pull all three strands snug at the same time, turn the rope over, locate the first twist in the line and repeat until you have all 3” – 4″ braided into the twisted rope.

Next, turn the rope over so you can see where the angled lines of the twisted rope begins again and feed the first strand under the first twist, the second under the second twist and the third under the third twist. Pull all three strands snug at the same time, turn the rope over, locate the first twist in the line and repeat until you have all 3” – 4″ braided into the twisted rope. You will have some loose ends sticking out and nylon rope can slip back out of the braid, so you now need to take a lighter and burn all these ends until they are melted together into the rope, so they will not slip. Be sure that you burn them so they are smooth and without bumps, or it will be difficult to feed the ends through the D-rings. Do the same with your second snap on the other end of the rope. Now you have your own custom made “Elbow Pull!”

You will have some loose ends sticking out and nylon rope can slip back out of the braid, so you now need to take a lighter and burn all these ends until they are melted together into the rope, so they will not slip. Be sure that you burn them so they are smooth and without bumps, or it will be difficult to feed the ends through the D-rings. Do the same with your second snap on the other end of the rope. Now you have your own custom made “Elbow Pull!”

underneath to attach to the lead rope) and our “Elbow Pull” self-correcting postural restraint. The bridle with the drop nose band will encourage your equine to take proper contact with the bit and not get in the habit of “waving” his tongue over the bit. Adjust it so it is taut enough to keep his head from going so high that he inverts his neck and back, and not so tight that it pulls his head too low. Stand in front of him once you have secured the “Elbow Pull” on the near side and rock his head from the poll to make sure the tension is correct.

underneath to attach to the lead rope) and our “Elbow Pull” self-correcting postural restraint. The bridle with the drop nose band will encourage your equine to take proper contact with the bit and not get in the habit of “waving” his tongue over the bit. Adjust it so it is taut enough to keep his head from going so high that he inverts his neck and back, and not so tight that it pulls his head too low. Stand in front of him once you have secured the “Elbow Pull” on the near side and rock his head from the poll to make sure the tension is correct. Begin the “Hourglass Pattern” without doing circles at the cones. Lead your animal with the lead rope in your left hand from the left side with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking left, and lead your animal with the lead rope in your right hand with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking right. Point your left hand (or right hand) in the direction of travel and look where you are going. Say the animal’s name and give the command to “Walk on.” Then look down to see what leg he is leading with and match your steps with his.

Begin the “Hourglass Pattern” without doing circles at the cones. Lead your animal with the lead rope in your left hand from the left side with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking left, and lead your animal with the lead rope in your right hand with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking right. Point your left hand (or right hand) in the direction of travel and look where you are going. Say the animal’s name and give the command to “Walk on.” Then look down to see what leg he is leading with and match your steps with his. You can set up your Hourglass Pattern as pictured above so you can do Leading Training, Obstacle Training, Lunging off and on the Lunge Line, Ground Driving Training and Riding Training without having to move things around. Putting ground rails between the two center cones will encourage your equine to use his hind quarters by stepping well underneath his center of gravity below his torso. This will elevate his front end and produce more action in his joints.

You can set up your Hourglass Pattern as pictured above so you can do Leading Training, Obstacle Training, Lunging off and on the Lunge Line, Ground Driving Training and Riding Training without having to move things around. Putting ground rails between the two center cones will encourage your equine to use his hind quarters by stepping well underneath his center of gravity below his torso. This will elevate his front end and produce more action in his joints. First he will get proficient on the lead rope in the Hourglass Pattern, and then obstacles will be added at the end of each lesson to facilitate coordination and further increase his postural core strength. During lunging training in good posture, he will be able to sustain equal weight over all four feet and won’t lean from one side to the other. His hind feet will fall into the footprints of the front feet. He will be able to stay in good balance with a consistent rhythm and cadence to all his gaits.

First he will get proficient on the lead rope in the Hourglass Pattern, and then obstacles will be added at the end of each lesson to facilitate coordination and further increase his postural core strength. During lunging training in good posture, he will be able to sustain equal weight over all four feet and won’t lean from one side to the other. His hind feet will fall into the footprints of the front feet. He will be able to stay in good balance with a consistent rhythm and cadence to all his gaits. Remember, when engaging in the Hourglass Pattern exercises, do not DRILL. You will only need to work your equine first one direction through the pattern with the designated halts between the cones, cross the diagonal and work in the other direction. Once around the pattern each way is enough to do the job. Work your equine a minimum of once a week and a maximum of once every other day. Be sure to leave a day of rest in between for the best results. Your equine will look forward to his time with you, so make the MOST of it!!

Remember, when engaging in the Hourglass Pattern exercises, do not DRILL. You will only need to work your equine first one direction through the pattern with the designated halts between the cones, cross the diagonal and work in the other direction. Once around the pattern each way is enough to do the job. Work your equine a minimum of once a week and a maximum of once every other day. Be sure to leave a day of rest in between for the best results. Your equine will look forward to his time with you, so make the MOST of it!! To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe and Twitter.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe and Twitter.

Horse trainers have kept us in awe of their unique and significant talents for centuries, and now that their techniques are more public, many equine professionals will pooh-pooh those who attempt a “kinder” approach to training. Scientists who study the equine in motion—its nutrition, biomechanics, care and maintenance—have their own perceptions to offer as to what we can learn about equines. Because many of these studies and tests are done in the laboratory, scientists rarely have the opportunity to follow their subjects throughout a lifetime of activity, as well as having the opportunity to experience what it really means for you as a rider, to be in balance with your equine when you work together, whether you are leading, lunging, riding or driving. If they did, their findings would probably yield quite different results. With all this progressive scientific thought, it seems to me that common sense can often get lost in the shuffle and respect for the living creature’s physical, mental and emotional needs may not be met.

Horse trainers have kept us in awe of their unique and significant talents for centuries, and now that their techniques are more public, many equine professionals will pooh-pooh those who attempt a “kinder” approach to training. Scientists who study the equine in motion—its nutrition, biomechanics, care and maintenance—have their own perceptions to offer as to what we can learn about equines. Because many of these studies and tests are done in the laboratory, scientists rarely have the opportunity to follow their subjects throughout a lifetime of activity, as well as having the opportunity to experience what it really means for you as a rider, to be in balance with your equine when you work together, whether you are leading, lunging, riding or driving. If they did, their findings would probably yield quite different results. With all this progressive scientific thought, it seems to me that common sense can often get lost in the shuffle and respect for the living creature’s physical, mental and emotional needs may not be met. degenerative breakdown. For instance, those who get in a hurry in Dressage and do not take a full year at each level in order to develop their equine’s body slowly and methodically may discover, several years later, that their animal has developed ringbone, side bones, arthritis or some other internal malady. These types of injuries and malformations are often not outwardly exhibited until it is too late to do anything about them.

degenerative breakdown. For instance, those who get in a hurry in Dressage and do not take a full year at each level in order to develop their equine’s body slowly and methodically may discover, several years later, that their animal has developed ringbone, side bones, arthritis or some other internal malady. These types of injuries and malformations are often not outwardly exhibited until it is too late to do anything about them.

Tragically, many equines are suffering from abuse every day, while they are trying to please their owners and do what is asked of them. Their owners and trainers take shortcuts that compromise the equine’s health. It could be that these owners and trainers are trying to make choices with limited knowledge and really don’t know whom to believe. But ignorance is not a valid defense and sadly, the animal is the one that ends up suffering.

Tragically, many equines are suffering from abuse every day, while they are trying to please their owners and do what is asked of them. Their owners and trainers take shortcuts that compromise the equine’s health. It could be that these owners and trainers are trying to make choices with limited knowledge and really don’t know whom to believe. But ignorance is not a valid defense and sadly, the animal is the one that ends up suffering. The Lucky Three mules have always been worked in good posture, and spend only as much time on the hot walker as it takes for them to dry after a bath. They maintain their good posture while walking and rarely let the hot walker “pull” them into bad posture.

The Lucky Three mules have always been worked in good posture, and spend only as much time on the hot walker as it takes for them to dry after a bath. They maintain their good posture while walking and rarely let the hot walker “pull” them into bad posture. Like many, I am of the belief that mechanical devices that force an equine into a rounded position do not necessarily put that equine in good posture. I would guess that many trainers think the “Elbow Pull” device that I use is guilty of developing this artificial posture. If that is their opinion, then they do not understand how it works. Rather than pulling the equine’s head down into a submissive position, when adjusted correctly, the “Elbow Pull” acts like a balance bar (like a ballet dancer would use) to help the equine to balance in good posture. It takes time to develop good posture. So, in the beginning, your equine can only sustain good posture for a certain number of measured steps, and then he must “lean” on the “Elbow Pull” in between these moments of sustaining his ideal balance on his own. The “Elbow Pull” simply prevents him from raising his head and neck so high that the neck becomes inverted and the back hollowed, but it does not actually pull his head down. The rope itself is very lightweight and puts virtually no weight on his head and neck at all. Note: Because horses react differently than mules and donkeys when hard-tied, a simple adjustment to allow the “Elbow Pull” to “slip” with a horse is necessary.

Like many, I am of the belief that mechanical devices that force an equine into a rounded position do not necessarily put that equine in good posture. I would guess that many trainers think the “Elbow Pull” device that I use is guilty of developing this artificial posture. If that is their opinion, then they do not understand how it works. Rather than pulling the equine’s head down into a submissive position, when adjusted correctly, the “Elbow Pull” acts like a balance bar (like a ballet dancer would use) to help the equine to balance in good posture. It takes time to develop good posture. So, in the beginning, your equine can only sustain good posture for a certain number of measured steps, and then he must “lean” on the “Elbow Pull” in between these moments of sustaining his ideal balance on his own. The “Elbow Pull” simply prevents him from raising his head and neck so high that the neck becomes inverted and the back hollowed, but it does not actually pull his head down. The rope itself is very lightweight and puts virtually no weight on his head and neck at all. Note: Because horses react differently than mules and donkeys when hard-tied, a simple adjustment to allow the “Elbow Pull” to “slip” with a horse is necessary.

distress and pain. This includes harsh bits, chain leads, twitches, hobbles, stocks and even medications. There are times when our equines can really be a handful, so having a little leverage when needed can be a good thing. However, deciding which equipment to use and learning how to use leverage without it becoming abusive can be a bit daunting. There are so many different types of tack, equipment and restraints that it becomes difficult to determine which would be best to use on your equine to correct a particular problem, or if you really need to use anything at all. It may only be a case of needing to be clearer in your approach, in which case, leverage equipment may not be needed. It is important to make an informed decision when using any leverage equipment to be sure that what you are using is helpful and not abusive.

distress and pain. This includes harsh bits, chain leads, twitches, hobbles, stocks and even medications. There are times when our equines can really be a handful, so having a little leverage when needed can be a good thing. However, deciding which equipment to use and learning how to use leverage without it becoming abusive can be a bit daunting. There are so many different types of tack, equipment and restraints that it becomes difficult to determine which would be best to use on your equine to correct a particular problem, or if you really need to use anything at all. It may only be a case of needing to be clearer in your approach, in which case, leverage equipment may not be needed. It is important to make an informed decision when using any leverage equipment to be sure that what you are using is helpful and not abusive. One very common behavioral problem that seems to identify the need for more leverage is the mule that bolts and runs when on the lead rope. This seems like an obvious disobedience to the handler, and the first thing that comes to mind is to use a lead shank with a chain to gain control of the mule. Normal use for a lead shank is during a Showmanship class at a show and it should rarely be used in training unless the equine will be shown at halter and/or showmanship. And then, training with the lead shank should be done only after the animal is following well through all required movements while in his halter and on a lead rope.

One very common behavioral problem that seems to identify the need for more leverage is the mule that bolts and runs when on the lead rope. This seems like an obvious disobedience to the handler, and the first thing that comes to mind is to use a lead shank with a chain to gain control of the mule. Normal use for a lead shank is during a Showmanship class at a show and it should rarely be used in training unless the equine will be shown at halter and/or showmanship. And then, training with the lead shank should be done only after the animal is following well through all required movements while in his halter and on a lead rope. If, after you’ve employed a kind, considerate and respectful approach along with a food reward, your equine is still being uncooperative, it may be appropriate to use equipment with more leverage such as the “Quick Twist,” but not necessarily chains. Chains do need to be used in some cases, such as with work harness (and most curb bits are now fitted with chains), but when not used correctly, these chains can be abusive. The chains on the pleasure driving harness should clear the legs and heels of the driving equine, and the chin chain on a curb bit should be adjusted so that it is twisted properly and lies flat against the animal’s jaw with an allowance of two fingers between the chain and the jaw, thereby minimizing any chance of injury. If you have a generally compliant equine, it is better to use a leather chin strap on your curb bit rather than a chain.

If, after you’ve employed a kind, considerate and respectful approach along with a food reward, your equine is still being uncooperative, it may be appropriate to use equipment with more leverage such as the “Quick Twist,” but not necessarily chains. Chains do need to be used in some cases, such as with work harness (and most curb bits are now fitted with chains), but when not used correctly, these chains can be abusive. The chains on the pleasure driving harness should clear the legs and heels of the driving equine, and the chin chain on a curb bit should be adjusted so that it is twisted properly and lies flat against the animal’s jaw with an allowance of two fingers between the chain and the jaw, thereby minimizing any chance of injury. If you have a generally compliant equine, it is better to use a leather chin strap on your curb bit rather than a chain. To employ the “Quick Twist” restraint, just take your lead rope and create a loop and feed it through the noseband of your nylon halter (rope halters are too loose and do not work) from back to front and then over the mule’s nose. When you pull on the rope, it will tighten around the end of the his nose below the incisive bones and over the cartilage, making breathing just a little difficult. Don’t keep pulling—just stand quietly and hold the tension snug. Let the equine come forward to you and slacken the rope himself by coming forward and allowing a free flow of air through his nostrils. Then, if the mule does not follow, just walk a step or two, creating tension on the rope, and then stand still again. When he does come forward, stop long enough to reward him with the oats reward before you proceed forward again. Keep the lead rope short and stand still in a balanced way so he cannot get ahead of you and jerk you off your feet. If you are standing still in a balanced position, it will be difficult for him to jerk the lead rope from your hand and leave.

To employ the “Quick Twist” restraint, just take your lead rope and create a loop and feed it through the noseband of your nylon halter (rope halters are too loose and do not work) from back to front and then over the mule’s nose. When you pull on the rope, it will tighten around the end of the his nose below the incisive bones and over the cartilage, making breathing just a little difficult. Don’t keep pulling—just stand quietly and hold the tension snug. Let the equine come forward to you and slacken the rope himself by coming forward and allowing a free flow of air through his nostrils. Then, if the mule does not follow, just walk a step or two, creating tension on the rope, and then stand still again. When he does come forward, stop long enough to reward him with the oats reward before you proceed forward again. Keep the lead rope short and stand still in a balanced way so he cannot get ahead of you and jerk you off your feet. If you are standing still in a balanced position, it will be difficult for him to jerk the lead rope from your hand and leave. Restraints should not be used as a means to control your animal except for a short period of time with the purpose of showing them a correct behavior. Restraints should be used as a support and not a controlling device. Restraints should be “phased out” as soon as possible.

Restraints should not be used as a means to control your animal except for a short period of time with the purpose of showing them a correct behavior. Restraints should be used as a support and not a controlling device. Restraints should be “phased out” as soon as possible. Do not try to bully him into it or he will just pull back. This should be done while he is standing parallel to the hitch rail so that when you pull the rope tight, it pulls his head tightly sideways to the hitch rail. This will keep him from being able to swing his rear end around to block you. Reward him with oats and let him quiet down in this restraint before approaching with your shot. If he manages to keep you off the clear side, you can always go to the other side of the hitch rail and give him the shot from that side without fear of injury. You can do this along a stout fence provided the rails are sturdy. If you do this correctly, it will simply restrain him in a safe manner and keep you out of the line of fire. Each new time that you give shots, try to do it with the rope a little looser each time to fade out the restraint. They will usually just come to expect and go for their position along the hitch rail or fence and will lean into it like they do when you first gave the shots like this. He will soon learn to quiet down immediately when his face is being tied and at best will seem to be saying, “Dang, do we have to do this again?!” But, he will learn to comply.

Do not try to bully him into it or he will just pull back. This should be done while he is standing parallel to the hitch rail so that when you pull the rope tight, it pulls his head tightly sideways to the hitch rail. This will keep him from being able to swing his rear end around to block you. Reward him with oats and let him quiet down in this restraint before approaching with your shot. If he manages to keep you off the clear side, you can always go to the other side of the hitch rail and give him the shot from that side without fear of injury. You can do this along a stout fence provided the rails are sturdy. If you do this correctly, it will simply restrain him in a safe manner and keep you out of the line of fire. Each new time that you give shots, try to do it with the rope a little looser each time to fade out the restraint. They will usually just come to expect and go for their position along the hitch rail or fence and will lean into it like they do when you first gave the shots like this. He will soon learn to quiet down immediately when his face is being tied and at best will seem to be saying, “Dang, do we have to do this again?!” But, he will learn to comply. This is a humane restraint for mules and donkeys, but do not try this with a horse! This is a good restraint to use (and fade out) for any Longears that is difficult to worm, give shots, take blood, clip bridle paths and to use for those that are difficult to bridle. When using the Face Tie for bridling training (or clipping the bridle path), you will only need to go through the noseband and hitch rail (and not through the throatlatch unless you need to prevent them from turning into you). Just make sure when you put on the bridle that you “protect” their sensitive ears with your hands as it goes on and they will learn to trust you. Put the bridle on over the halter for the lessons until they don’t mind the bridling process.

This is a humane restraint for mules and donkeys, but do not try this with a horse! This is a good restraint to use (and fade out) for any Longears that is difficult to worm, give shots, take blood, clip bridle paths and to use for those that are difficult to bridle. When using the Face Tie for bridling training (or clipping the bridle path), you will only need to go through the noseband and hitch rail (and not through the throatlatch unless you need to prevent them from turning into you). Just make sure when you put on the bridle that you “protect” their sensitive ears with your hands as it goes on and they will learn to trust you. Put the bridle on over the halter for the lessons until they don’t mind the bridling process. Your Longears will only need the kicking training covered in

Your Longears will only need the kicking training covered in  the hind foot, around the pastern and let it lay on the floor. Next time, you won’t have to use it at all. Your goal is to phase out the restraint entirely.

the hind foot, around the pastern and let it lay on the floor. Next time, you won’t have to use it at all. Your goal is to phase out the restraint entirely. Hobbles are another form of leverage equipment and there are many different kinds of hobbles for different purposes. The hobbles that have chains on them should be avoided, as the equine can become entangled and the chains can do damage to their legs. Thin leather hobbles or coarse rope can chafe the hair right off the skin around the pastern and can cause severe abrasions that may never heal. Thick leather hobbles are best, as they will break when under extreme stress, releasing before damage to the equine is done. If so inclined, all mules and some horses can gallop in hobbles, so hobbles really aren’t all that effective for leverage. Tying onto a hyline (a rope suspended high between two trees that acts as a hitching line for overnighting equines in the mountains) is a better choice, and if the horses are tied, then the mules should not have to be tied or hobbled because they will generally stay with the horses. Personally, I only use hobbles in a controlled situation at the work station when body clipping my equine’s legs for show.

Hobbles are another form of leverage equipment and there are many different kinds of hobbles for different purposes. The hobbles that have chains on them should be avoided, as the equine can become entangled and the chains can do damage to their legs. Thin leather hobbles or coarse rope can chafe the hair right off the skin around the pastern and can cause severe abrasions that may never heal. Thick leather hobbles are best, as they will break when under extreme stress, releasing before damage to the equine is done. If so inclined, all mules and some horses can gallop in hobbles, so hobbles really aren’t all that effective for leverage. Tying onto a hyline (a rope suspended high between two trees that acts as a hitching line for overnighting equines in the mountains) is a better choice, and if the horses are tied, then the mules should not have to be tied or hobbled because they will generally stay with the horses. Personally, I only use hobbles in a controlled situation at the work station when body clipping my equine’s legs for show. I do not approve of using power tools on the equine’s hooves at all. In order for the equine’s body to be properly balanced in good posture, the hooves must first be properly balanced. Power tools cannot possibly shape the hoof with proper curvature in the sole, alignment of angles and equal balance over the hoof walls with appropriate pressure to the heels and frog.

I do not approve of using power tools on the equine’s hooves at all. In order for the equine’s body to be properly balanced in good posture, the hooves must first be properly balanced. Power tools cannot possibly shape the hoof with proper curvature in the sole, alignment of angles and equal balance over the hoof walls with appropriate pressure to the heels and frog.

First, you should be sure that the trailer in which they are to ride affords safety and comfort and that the plates on both the truck and trailer are up-to-date. Before you leave, you should check over your trailer thoroughly. Make sure the hitch is secure and in good repair, and that there are no weakened welds anywhere. Check your trailer’s tires, bearings, axels and brakes for maximum performance, and make sure all the lights are in working order. Take the trailer mats out and check the floor boards for rot and other weaknesses, and replace all floor boards that are even questionable. It is always good practice to get all new tires for the trip and a new spare.

First, you should be sure that the trailer in which they are to ride affords safety and comfort and that the plates on both the truck and trailer are up-to-date. Before you leave, you should check over your trailer thoroughly. Make sure the hitch is secure and in good repair, and that there are no weakened welds anywhere. Check your trailer’s tires, bearings, axels and brakes for maximum performance, and make sure all the lights are in working order. Take the trailer mats out and check the floor boards for rot and other weaknesses, and replace all floor boards that are even questionable. It is always good practice to get all new tires for the trip and a new spare. Mules and donkeys, like horses, should be “dressed” for their trip. For their overall comfort during long trips, halters should be fleeced, at least over the noseband, to protect from excessive rubbing that can result from being tied. Shipping wraps for their legs are also advisable to prevent injuries from a loss of balance, misstep or kick from another animal in the trailer. Depending on the weather and the kind of trailer you have (either a stock trailer or enclosed trailer) you can use sheets or blankets to protect the rest of your animal’s body.

Mules and donkeys, like horses, should be “dressed” for their trip. For their overall comfort during long trips, halters should be fleeced, at least over the noseband, to protect from excessive rubbing that can result from being tied. Shipping wraps for their legs are also advisable to prevent injuries from a loss of balance, misstep or kick from another animal in the trailer. Depending on the weather and the kind of trailer you have (either a stock trailer or enclosed trailer) you can use sheets or blankets to protect the rest of your animal’s body. When loading your mules and donkeys, pay special attention to each individual’s needs. Animals that lean one way or the other generally do better in a slant load trailer rather than in an in-line trailer, but if you must use an in-line trailer, make sure that the animal that leans has a solid wall or partition on the side to which he leans. You always want to put animals next to each other that get along well, so if you must load a leaner on the wrong side, be sure to put him next to an animal that is able to tolerate his leaning without retaliating if there are no partitions. If you have an open stock trailer, another alternative is to load your animals into the trailer and tie them facing backwards. Many equines actually prefer to ride facing backwards because they find it easier to balance. Note: This alternative is not advisable in a partitioned in-line or slant-load trailer.

When loading your mules and donkeys, pay special attention to each individual’s needs. Animals that lean one way or the other generally do better in a slant load trailer rather than in an in-line trailer, but if you must use an in-line trailer, make sure that the animal that leans has a solid wall or partition on the side to which he leans. You always want to put animals next to each other that get along well, so if you must load a leaner on the wrong side, be sure to put him next to an animal that is able to tolerate his leaning without retaliating if there are no partitions. If you have an open stock trailer, another alternative is to load your animals into the trailer and tie them facing backwards. Many equines actually prefer to ride facing backwards because they find it easier to balance. Note: This alternative is not advisable in a partitioned in-line or slant-load trailer. Long before you actually go anywhere, get your animals used to being handled inside the trailer. When unloading, always make them stand and wait. I usually remove my animals’ shipping wraps before I let them come out of the trailer, but if they are packed in pretty tightly, I just remove the leg wraps I can reach. The removal of leg wraps before unloading will add purpose to your Longears’ waiting time (which they quickly come to understand). Frequently offering water at stops gets your animals used to you moving about the trailer while they are loaded. Most equines realize that all of this is for their benefit and you should find them mostly cooperative and appreciative. Having water from home in plastic jugs makes this easy.

Long before you actually go anywhere, get your animals used to being handled inside the trailer. When unloading, always make them stand and wait. I usually remove my animals’ shipping wraps before I let them come out of the trailer, but if they are packed in pretty tightly, I just remove the leg wraps I can reach. The removal of leg wraps before unloading will add purpose to your Longears’ waiting time (which they quickly come to understand). Frequently offering water at stops gets your animals used to you moving about the trailer while they are loaded. Most equines realize that all of this is for their benefit and you should find them mostly cooperative and appreciative. Having water from home in plastic jugs makes this easy.

(NOTE: I don’t recommend riding along paved roads at all these days. Although you and your equine may be in control, motorists don’t always pay attention while they are driving—which can lead to disaster.)

(NOTE: I don’t recommend riding along paved roads at all these days. Although you and your equine may be in control, motorists don’t always pay attention while they are driving—which can lead to disaster.) Good habits are built through repetition and reward with regard to consideration for your equine. Eventually, the good habits that are being taught will become the normal way that your animal will move and react to you and to his environment. The details outlined in this article can help contribute to the behavior shaping of your animal, which will determine, as he ages, how willing and obedient he will be in all situations.

Good habits are built through repetition and reward with regard to consideration for your equine. Eventually, the good habits that are being taught will become the normal way that your animal will move and react to you and to his environment. The details outlined in this article can help contribute to the behavior shaping of your animal, which will determine, as he ages, how willing and obedient he will be in all situations.

We are fortunate to be able to share our time with such intelligent, tough and durable equines as our beloved mules. But you should also remember to do your part in the relationship. Be patient and willing to take the time to allow your relationship to grow and for training to become solid before you indulge in the challenges that trail riding can present. Plan ahead and scout the locations where you desire to ride. With the growth of urban populations, open areas that welcomed riders in the past are not as numerous as they once were. Many areas now welcome hikers and even bicycles, but not equines. Find the designated trails and camp grounds that will accept equines when planning your treks.

We are fortunate to be able to share our time with such intelligent, tough and durable equines as our beloved mules. But you should also remember to do your part in the relationship. Be patient and willing to take the time to allow your relationship to grow and for training to become solid before you indulge in the challenges that trail riding can present. Plan ahead and scout the locations where you desire to ride. With the growth of urban populations, open areas that welcomed riders in the past are not as numerous as they once were. Many areas now welcome hikers and even bicycles, but not equines. Find the designated trails and camp grounds that will accept equines when planning your treks. Even a ride that is planned to be short can turn into challenge if the weather changes suddenly, so be sure to plan for the worst case scenario. Tack up your equine in comfortable tack and equipment that fits like a glove. I like to ride with a crupper because it will hold the saddle in the correct placement when adjusted correctly and will allow for full range of movement, particularly behind when climbing uphill. If you use a breast collar, make sure it is loosely fitted so it does not pull your saddle forward and into the shoulder blades. Be sure to pack your saddle bags with the barest necessities for any ride far from home: Compass, water, rain gear, a Swiss Army knife, buck knife, hoof pick, lighter, fence pliers, Granola Bars or Trail Mix, a sleeping bag, a warm coat, Bear Spray and a First Aid Kit (at the very least Gauze, Vet Wrap and Neosporin).

Even a ride that is planned to be short can turn into challenge if the weather changes suddenly, so be sure to plan for the worst case scenario. Tack up your equine in comfortable tack and equipment that fits like a glove. I like to ride with a crupper because it will hold the saddle in the correct placement when adjusted correctly and will allow for full range of movement, particularly behind when climbing uphill. If you use a breast collar, make sure it is loosely fitted so it does not pull your saddle forward and into the shoulder blades. Be sure to pack your saddle bags with the barest necessities for any ride far from home: Compass, water, rain gear, a Swiss Army knife, buck knife, hoof pick, lighter, fence pliers, Granola Bars or Trail Mix, a sleeping bag, a warm coat, Bear Spray and a First Aid Kit (at the very least Gauze, Vet Wrap and Neosporin). If planning an overnight trip, you will probably need a pack mule, or horse, to carry the extra food and additional necessities you will need like tents, blankets, sleeping bags, more food, extra clothes, High Lines and extra halters, and food for your equines. Lots of places will not allow your equines to graze in the parks, but some do. I do not like using picket lines where the equine is tied low with a halter, or with a rope around a foot. I do not like to use hobbles either (Mules can run off in hobbles with no trouble at all!). It is too easy for equines to get tangled up or injure themselves when they are restricted this way. They can get sprained tendons and ligaments, or severe rope burns that will leave them scarred for life. I prefer to bring their favorite horse “friend” along and tie the horse, and mules that tend to wander, to a High Line. Most of the mules can be allowed to run free and won’t leave your camp with the horse there, but do not leave halters on them. Again, they could become tangled up and injure themselves. If you have spent adequate time during training to build a solid relationship with your mules, they are much less likely to wander off and get lost. They will choose to stay near you.

If planning an overnight trip, you will probably need a pack mule, or horse, to carry the extra food and additional necessities you will need like tents, blankets, sleeping bags, more food, extra clothes, High Lines and extra halters, and food for your equines. Lots of places will not allow your equines to graze in the parks, but some do. I do not like using picket lines where the equine is tied low with a halter, or with a rope around a foot. I do not like to use hobbles either (Mules can run off in hobbles with no trouble at all!). It is too easy for equines to get tangled up or injure themselves when they are restricted this way. They can get sprained tendons and ligaments, or severe rope burns that will leave them scarred for life. I prefer to bring their favorite horse “friend” along and tie the horse, and mules that tend to wander, to a High Line. Most of the mules can be allowed to run free and won’t leave your camp with the horse there, but do not leave halters on them. Again, they could become tangled up and injure themselves. If you have spent adequate time during training to build a solid relationship with your mules, they are much less likely to wander off and get lost. They will choose to stay near you. If you can, choose a place where you can establish a base and park your truck and trailer. You can then tie them on a High Line during the evening and put them back into the trailer for the night. This might be better if you are an area where there are a lot of large predators. Just don’t leave the truck and trailer windows open so a predator can get in. Stock trailers are the best for this purpose since they also have more room in them and are fully enclosed. Any food that could be attractive to predators should be mounted high in a tree, at least 50-100 yards away from your camp and your equines.

If you can, choose a place where you can establish a base and park your truck and trailer. You can then tie them on a High Line during the evening and put them back into the trailer for the night. This might be better if you are an area where there are a lot of large predators. Just don’t leave the truck and trailer windows open so a predator can get in. Stock trailers are the best for this purpose since they also have more room in them and are fully enclosed. Any food that could be attractive to predators should be mounted high in a tree, at least 50-100 yards away from your camp and your equines.

Once your equine has mastered tying and leading in the small pen, he can then move on to a designated work station where he will not only be groomed, but will also learn to accept tack in preparation for the round pen. This should be a place that has a good stout hitch rail and easy access to your tack and grooming equipment.