MULE CROSSING: The Hourglass Pattern & The Elbow Pull

(A SELF-CORRECTING POSTURAL AID FOR EQUINES)

Concept Developed by Richard Shrake and Specific Design by Meredith Hodges

(Trademarked & Published in TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE 2003)

In my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the SPECIAL FEATURES of my EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), I talk about using a postural aid called the “Elbow Pull.” In the EQUUS REVISITED DVD, we teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. If you have our video series, in DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), we talk about using the “Elbow Pull.” We teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. The “Elbow Pull” puts your animal into your equine’s ideal posture. He will have full range of motion in every direction when it is adjusted correctly. He will just not be able to raise his head so high that he hollows his neck and back.

In my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the SPECIAL FEATURES of my EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), I talk about using a postural aid called the “Elbow Pull.” In the EQUUS REVISITED DVD, we teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. If you have our video series, in DVD #2, in the TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE manual (2003) and in the EQUUS REVISITED DVD (2009), we talk about using the “Elbow Pull.” We teach you how to measure it for your individual equine and how to make it. The “Elbow Pull” puts your animal into your equine’s ideal posture. He will have full range of motion in every direction when it is adjusted correctly. He will just not be able to raise his head so high that he hollows his neck and back.

He will be able to balance and adjust his body position, encourage the hind quarters to come underneath his body when he is walked, or driven forward. Allowing the equine take short steps, front and back, would let the back sag (swayback-Lordosis) and does not engage the abdominal muscles. The “Elbow Pull” encourages the equine to stretch his spine, round his back and neck upwards (not “hump” it!) and elevates the shoulders when he steps  underneath his body. The elevation (or suspension) in the shoulders allows him to increase the “reach” in his front legs. I use the “Elbow Pull” for Leading Training, Ground Driving and when he is ready, Lunging in the Round Pen. The Leading Training on flat ground through our HOURGLASS PATTERN positively affects his overall postural balance, and Leading through Obstacles adds coordination. You know that he is ready to go on to each stage of Leading Training on flat ground (and then through obstacles) when you can throw the lead rope over his neck and do the exercises with verbal commands, hand signals and body language alone. This is building a new habitual way of traveling is all in preparation for Lunging correctly…keeping his body erect and in a symmetrical balance while he bends to the arc of the circle through his torso without leaning like a motorcycle. It will prevent muscle compromises throughout his body that could cause soreness and compromise organ function.

underneath his body. The elevation (or suspension) in the shoulders allows him to increase the “reach” in his front legs. I use the “Elbow Pull” for Leading Training, Ground Driving and when he is ready, Lunging in the Round Pen. The Leading Training on flat ground through our HOURGLASS PATTERN positively affects his overall postural balance, and Leading through Obstacles adds coordination. You know that he is ready to go on to each stage of Leading Training on flat ground (and then through obstacles) when you can throw the lead rope over his neck and do the exercises with verbal commands, hand signals and body language alone. This is building a new habitual way of traveling is all in preparation for Lunging correctly…keeping his body erect and in a symmetrical balance while he bends to the arc of the circle through his torso without leaning like a motorcycle. It will prevent muscle compromises throughout his body that could cause soreness and compromise organ function.

I continue to use the “Elbow Pull” with each new stage of training to help him maintain his good posture throughout the different tasks. It is a supportive device and when he has problems with his posture, it will become tight. He can “lean” against it for a few strides without going totally out of good posture which gives him relief from the stress of trying to hold his good posture for long periods of time, which is often difficult in the beginning.

When he is again able to hold his good posture, the aid becomes loose all over. The equine is in complete control of this postural aid. Even people have problems maintaining good posture without the occasional reminder of their own good posture until it becomes more habitual.

None of us were born in good posture. It is something that must be taught. If we are allowed to “slouch” in our posture, it WILL create soreness and physical problems over time, especially when we get much older. After Lunging in good posture for several months, the equine’s habitual way of going will be changed. He will begin to travel in good posture automatically.

None of us were born in good posture. It is something that must be taught. If we are allowed to “slouch” in our posture, it WILL create soreness and physical problems over time, especially when we get much older. After Lunging in good posture for several months, the equine’s habitual way of going will be changed. He will begin to travel in good posture automatically.

Changing habits takes a long time of repetitive behavior to evolve into a new habitual way of acting. As you teach your body through these stages to stay in sync with your equine’s steps, YOUR body becomes more in tune with his way of going and prepares you to be a better rider. This is all a matter or re-programming brain-muscle impulses. The equine will be Ground Driven in the “Elbow Pull” as he adjusts to learning rein cues, and when the weight of the rider is finally added, it is advisable to ride in the “Elbow Pull” until it remains loose all the time. When it does, you can be sure he is strong in his core balance and truly ready to support the rider in any kind of athletic pursuit. The equine learns to carry the rider on top of an upward arc in their spine with the abdominal muscles engaged. This is the same as teaching people to use their whole body correctly and lift with  their legs and not their backs. These kinds of exercises make sure that the animal travels symmetrically, allowing the joints to work as they were designed to do (according to the laws of physics) with no compromises, and promotes optimum function of their internal organs.

their legs and not their backs. These kinds of exercises make sure that the animal travels symmetrically, allowing the joints to work as they were designed to do (according to the laws of physics) with no compromises, and promotes optimum function of their internal organs.

With an equine that is over 2 years old and that has not had the benefit of developing core strength in good posture, it is advisable to first use the “Elbow Pull” during detailed and extensive Leading Lessons, both on the flat ground and later over obstacles. An equine under two years of age will not need the “Elbow Pull” support while working on his way of going since repetitive habits have not yet been fully established.

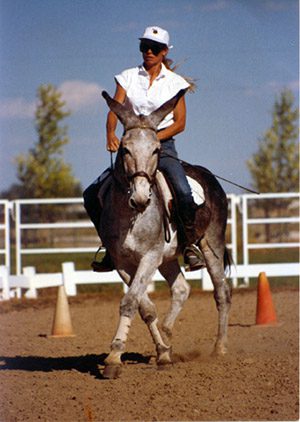

Lunge the equine in the Round Pen for several months until the animal habitually exhibits an erect posture with equal weight over all four feet and balanced self-body carriage. When you finally begin riding, you should use the “Elbow Pull” while you are riding our Hourglass Pattern under saddle as he adjusts to the added weight and new balance. When the “Elbow Pull” is adjusted correctly and the equine is in good posture, it will not put any pressure on the animal at all. When he is out of good posture, it puts pressure on the poll, the bit rings, behind the forearms and over the back. He will go back to his good posture as soon as he is able in order to release the pressure points.

Lunge the equine in the Round Pen for several months until the animal habitually exhibits an erect posture with equal weight over all four feet and balanced self-body carriage. When you finally begin riding, you should use the “Elbow Pull” while you are riding our Hourglass Pattern under saddle as he adjusts to the added weight and new balance. When the “Elbow Pull” is adjusted correctly and the equine is in good posture, it will not put any pressure on the animal at all. When he is out of good posture, it puts pressure on the poll, the bit rings, behind the forearms and over the back. He will go back to his good posture as soon as he is able in order to release the pressure points.

Place the “Elbow Pull” over the poll, through the snaffle bit rings, between the animal’s front legs and over the back, then snap the two ends to a surcingle D-ring or D-rings, on the saddle you are using. It should be adjusted so he can only raise his head approximately 3-4 inches above the level of the withers (just before he hollows his neck and back). The “Elbow Pull” needs to be adjusted loosely enough so that he can relieve the pressure at the poll, bit rings, elbows and back without having to drop his head below the withers.

Place the “Elbow Pull” over the poll, through the snaffle bit rings, between the animal’s front legs and over the back, then snap the two ends to a surcingle D-ring or D-rings, on the saddle you are using. It should be adjusted so he can only raise his head approximately 3-4 inches above the level of the withers (just before he hollows his neck and back). The “Elbow Pull” needs to be adjusted loosely enough so that he can relieve the pressure at the poll, bit rings, elbows and back without having to drop his head below the withers.

When lunging, if the “Elbow Pull” is correctly adjusted and he still wants to carry his nose to the ground, encouraging him with the whip to speed him up a bit. This will encourage him to engage his hindquarters and raise his head into the correct position. The only way he can really go forward with his nose to the ground is if the hind quarters are not engaged. As soon as the hindquarters are engaged, he will have to raise his head to the correct position to maintain his balance. When being led in the “Elbow Pull,” lowering the head is not a problem because you will have control of the lead rope attached a ring underneath his noseband or a halter (not attached to the bit!). Doing stretching-down exercises during leading training helps to stretch the spine and alleviate any soreness that could be developing with the new postural position. Breaking old habitual muscle positions can cause soreness to begin with, but as the better posture becomes more evolved, it also becomes much more comfortable (as it does in humans). Stay away from medications as much as possible as he works his way to the new posture.

In the Round Pen, the “Elbow Pull” helps the animal learn to travel in good equine posture without the added weight of a rider first. In doing so, it increases his core strength and the ability for him to carry a more balanced posture of his own volition. The added weight of the rider under saddle will challenge the animal again to maintain this good posture. This will take further strengthening of the muscles. The “Elbow Pull” will keep the animal in the correct posture while carrying the rider, so he doesn’t ever build muscle out of balance and out of good equine posture. When you do this, you are changing old habitual movement into good equine posture and a balanced way of moving. This eventually (after two years) will become his habitual way of moving and playing, even during turnout.

In the Round Pen, the “Elbow Pull” helps the animal learn to travel in good equine posture without the added weight of a rider first. In doing so, it increases his core strength and the ability for him to carry a more balanced posture of his own volition. The added weight of the rider under saddle will challenge the animal again to maintain this good posture. This will take further strengthening of the muscles. The “Elbow Pull” will keep the animal in the correct posture while carrying the rider, so he doesn’t ever build muscle out of balance and out of good equine posture. When you do this, you are changing old habitual movement into good equine posture and a balanced way of moving. This eventually (after two years) will become his habitual way of moving and playing, even during turnout.

Your equine should stay in the “Elbow Pull” when working for two years to make sure that the muscles are indeed conditioned around correct equine posture through correct and consistent repetition. This means that when your year of Lunging, then Ground Driving is over, and he begins to work with a rider or while being driven, you would still use the “Elbow Pull” to help him stay in good posture for another year with the added weight of the rider on his back. If driving your equine, you should also use it during the first two years in your driving arena during training to promote good equine driving posture and engagement of the hind quarters while pulling. This assures that the muscles are becoming correctly and symmetrically strong (supporting the skeleton), over a balanced and physically aligned frame.

If you are consistent during his lessons, being in good equine posture will become his normal way of going and will not disappear when you finally ride without it.

If you are consistent during his lessons, being in good equine posture will become his normal way of going and will not disappear when you finally ride without it.

The “Elbow Pull” postural aid does not pull their head down. Rather, it gives them full range of motion (up, down, and sideways), but keeps them from raising their heads so high that they hollow their back and neck during initial training. It is a fully self-correcting restraint that gives them something to lean on when they are not yet strong enough in the core (elements that support the skeletal frame…muscles, tendons, ligaments, connective tissue and even cartilage in the joints) to maintain their ideal balance. It encourages them to step well underneath their body, round their back upward from head to tail and puts the spine in an position to allow space between the vertebrae Spinus Processes (and avoid “Kissing Spine”) and to prevent the rider from injuring their spine (according to the laws of Physics). The “Elbow Pull” provides support much like a balance bar does for a beginning ballet dancer, and the principles of good posture are the same as with humans.

and to prevent the rider from injuring their spine (according to the laws of Physics). The “Elbow Pull” provides support much like a balance bar does for a beginning ballet dancer, and the principles of good posture are the same as with humans.

Repetition and consistency during training can change habitual bad posture to habitual good posture over a long period of time, usually about two years. Good posture and correct movement can enhance longevity by as much as 5-10 years, enable internal organs to operate efficiently and prevent calcification, arthritis and other compromises like locked stifles that can create soreness in the body.

There is a much different way to secure the “Elbow Pull on a horse. Horses have violent reactions to a hard tie, so  you will need to cross the rope across their back, pull it taut into the correct tension and then secure the snaps, keeping plenty of slack in the rope. You want the rope semi-knot to slip if they brace against it, but you do not want loose snaps on the ends of the rope to swing free to hit the horse anywhere on his body. With horses, you would just twist the rope over the back as shown in the photo, so the snaps are a moot point until the horse learns to give to the Elbow Pull and can be hard tied.

you will need to cross the rope across their back, pull it taut into the correct tension and then secure the snaps, keeping plenty of slack in the rope. You want the rope semi-knot to slip if they brace against it, but you do not want loose snaps on the ends of the rope to swing free to hit the horse anywhere on his body. With horses, you would just twist the rope over the back as shown in the photo, so the snaps are a moot point until the horse learns to give to the Elbow Pull and can be hard tied.

Making the “Elbow Pull”

Although the “Elbow Pull” is a very simple and straight forward aid to help keep your equine in good posture, it is also a device that needs to be custom made to fit each individual equine. Equines that approximate the same size in the front quarters will probably be able to use the same one. First, you need to obtain a package of 3/8″ X 50′ nylon and polyester twisted rope. This is the way it is sold. Do not substitute any other kind of rope, or leather reins, etc. as this will have a different weight and slippage around the bridle and will not have the same effect.

Although the “Elbow Pull” is a very simple and straight forward aid to help keep your equine in good posture, it is also a device that needs to be custom made to fit each individual equine. Equines that approximate the same size in the front quarters will probably be able to use the same one. First, you need to obtain a package of 3/8″ X 50′ nylon and polyester twisted rope. This is the way it is sold. Do not substitute any other kind of rope, or leather reins, etc. as this will have a different weight and slippage around the bridle and will not have the same effect.

You will also need two snaps that are narrow, yet fairly strong that can fit easily through the D-rings on your surcingle, or Western saddle. English saddle D-rings are generally too small and in this situation, we do not attach to them, but rather attach the “Elbow Pull” to itself over the top of the spine. If the rope tends to twist and the snaps slide off to the side, you can often just snap one snap to the D-ring and the other snap snapped to the first snap, or if the “Elbow Pull” is a bit shorter, you can just snap it to the small D-ring on each side. The reason for twisted rope is so you can actually go through the D-rings and snap it into the twisted rope itself for a more exact setting. You would just untwist the rope at the setting point and snap into the middle of the rope so it won’t slide.

You will also need two snaps that are narrow, yet fairly strong that can fit easily through the D-rings on your surcingle, or Western saddle. English saddle D-rings are generally too small and in this situation, we do not attach to them, but rather attach the “Elbow Pull” to itself over the top of the spine. If the rope tends to twist and the snaps slide off to the side, you can often just snap one snap to the D-ring and the other snap snapped to the first snap, or if the “Elbow Pull” is a bit shorter, you can just snap it to the small D-ring on each side. The reason for twisted rope is so you can actually go through the D-rings and snap it into the twisted rope itself for a more exact setting. You would just untwist the rope at the setting point and snap into the middle of the rope so it won’t slide.

Have the equine stand at the hitch rail with the snaffle bridle on. To get a measurement for how long a piece of rope you will need for his “Elbow Pull,” take a length of rope from the coil. Feed the end of the rope from the inside to the outside of the snaffle bit ring, drape it over the poll of your equine and feed it from the outside of the snaffle bit ring to the inside on the opposite side of your equine. Then pull enough slack to go down through the front legs, behind the forearm, up and over the back such that it hangs one foot, or more (but not less) on the other side of the spine. Then, go back to the side on which you started and do the same on that side with the remainder of the 50″ foot length of rope and cut the rope at the 1-foot mark on the other side of the spine.

Have the equine stand at the hitch rail with the snaffle bridle on. To get a measurement for how long a piece of rope you will need for his “Elbow Pull,” take a length of rope from the coil. Feed the end of the rope from the inside to the outside of the snaffle bit ring, drape it over the poll of your equine and feed it from the outside of the snaffle bit ring to the inside on the opposite side of your equine. Then pull enough slack to go down through the front legs, behind the forearm, up and over the back such that it hangs one foot, or more (but not less) on the other side of the spine. Then, go back to the side on which you started and do the same on that side with the remainder of the 50″ foot length of rope and cut the rope at the 1-foot mark on the other side of the spine.

Once you have the proper length of rope for your equine, you will need to unravel 3” – 4″ of one end of the rope and loop it through the ring on your first snap. Then you will braid the rope back into itself. First, pick the loose strand that is on top as you lay the rope across your hand, bend it around the end of the snap and feed it under a twist of the rope such that it creates a loop around the end of your snap and pull it snug. Then take the next loose strand (which would be the middle of the three strands) and feed it under the next twist down from the one you just did. Then do the same with the third loose strand under the third twist in the rope. Take all three strands in your hand, hold the rope so it doesn’t twist and pull all three strands snug. They should all line up.

Once you have the proper length of rope for your equine, you will need to unravel 3” – 4″ of one end of the rope and loop it through the ring on your first snap. Then you will braid the rope back into itself. First, pick the loose strand that is on top as you lay the rope across your hand, bend it around the end of the snap and feed it under a twist of the rope such that it creates a loop around the end of your snap and pull it snug. Then take the next loose strand (which would be the middle of the three strands) and feed it under the next twist down from the one you just did. Then do the same with the third loose strand under the third twist in the rope. Take all three strands in your hand, hold the rope so it doesn’t twist and pull all three strands snug. They should all line up.

Next, turn the rope over so you can see where the angled lines of the twisted rope begins again and feed the first strand under the first twist, the second under the second twist and the third under the third twist. Pull all three strands snug at the same time, turn the rope over, locate the first twist in the line and repeat until you have all 3” – 4″ braided into the twisted rope.

Next, turn the rope over so you can see where the angled lines of the twisted rope begins again and feed the first strand under the first twist, the second under the second twist and the third under the third twist. Pull all three strands snug at the same time, turn the rope over, locate the first twist in the line and repeat until you have all 3” – 4″ braided into the twisted rope.

You will have some loose ends sticking out and nylon rope can slip back out of the braid, so you now need to take a lighter and burn all these ends until they are melted together into the rope, so they will not slip. Be sure that you burn them so they are smooth and without bumps, or it will be difficult to feed the ends through the D-rings. Do the same with your second snap on the other end of the rope. Now you have your own custom made “Elbow Pull!”

You will have some loose ends sticking out and nylon rope can slip back out of the braid, so you now need to take a lighter and burn all these ends until they are melted together into the rope, so they will not slip. Be sure that you burn them so they are smooth and without bumps, or it will be difficult to feed the ends through the D-rings. Do the same with your second snap on the other end of the rope. Now you have your own custom made “Elbow Pull!”

THE HOURGLASS PATTERN

(Core Strength Leading Training)

Tack up your animal in a surcingle (or lightweight saddle), a snaffle bridle with a drop noseband (and a ring  underneath to attach to the lead rope) and our “Elbow Pull” self-correcting postural restraint. The bridle with the drop nose band will encourage your equine to take proper contact with the bit and not get in the habit of “waving” his tongue over the bit. Adjust it so it is taut enough to keep his head from going so high that he inverts his neck and back, and not so tight that it pulls his head too low. Stand in front of him once you have secured the “Elbow Pull” on the near side and rock his head from the poll to make sure the tension is correct.

underneath to attach to the lead rope) and our “Elbow Pull” self-correcting postural restraint. The bridle with the drop nose band will encourage your equine to take proper contact with the bit and not get in the habit of “waving” his tongue over the bit. Adjust it so it is taut enough to keep his head from going so high that he inverts his neck and back, and not so tight that it pulls his head too low. Stand in front of him once you have secured the “Elbow Pull” on the near side and rock his head from the poll to make sure the tension is correct.

Begin the “Hourglass Pattern” without doing circles at the cones. Lead your animal with the lead rope in your left hand from the left side with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking left, and lead your animal with the lead rope in your right hand with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking right. Point your left hand (or right hand) in the direction of travel and look where you are going. Say the animal’s name and give the command to “Walk on.” Then look down to see what leg he is leading with and match your steps with his.

Begin the “Hourglass Pattern” without doing circles at the cones. Lead your animal with the lead rope in your left hand from the left side with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking left, and lead your animal with the lead rope in your right hand with your equine’s head at your shoulder when tracking right. Point your left hand (or right hand) in the direction of travel and look where you are going. Say the animal’s name and give the command to “Walk on.” Then look down to see what leg he is leading with and match your steps with his.

When you stop, say “And…Whoa” and stop with your feet together. Square him up with both hind legs together and then put both front legs together with equal weight over all four feet and reward from a fanny pack of oats around your waist. Stand quietly until he has finished chewing, change sides (and leading position) after every halt so you are always leading from the “inside” of the arc on which you are traveling, and give the command to “Walk on.” You can add circles at the cones and ground rails once he is consistently walking at your shoulder and prompt with the commands.

You can set up your Hourglass Pattern as pictured above so you can do Leading Training, Obstacle Training, Lunging off and on the Lunge Line, Ground Driving Training and Riding Training without having to move things around. Putting ground rails between the two center cones will encourage your equine to use his hind quarters by stepping well underneath his center of gravity below his torso. This will elevate his front end and produce more action in his joints.

You can set up your Hourglass Pattern as pictured above so you can do Leading Training, Obstacle Training, Lunging off and on the Lunge Line, Ground Driving Training and Riding Training without having to move things around. Putting ground rails between the two center cones will encourage your equine to use his hind quarters by stepping well underneath his center of gravity below his torso. This will elevate his front end and produce more action in his joints.

I work multiple animals, up to four at a time by working one in the arena (with and without the lead rope) with the others tied at the hitch rail just outside the arena by the gate. This enables me to get multiple equines done in a short amount of time and reduces the incidence of animals pacing the fence while others are being worked. Using your facility efficiently can greatly reduce time spent on training.

First he will get proficient on the lead rope in the Hourglass Pattern, and then obstacles will be added at the end of each lesson to facilitate coordination and further increase his postural core strength. During lunging training in good posture, he will be able to sustain equal weight over all four feet and won’t lean from one side to the other. His hind feet will fall into the footprints of the front feet. He will be able to stay in good balance with a consistent rhythm and cadence to all his gaits.

First he will get proficient on the lead rope in the Hourglass Pattern, and then obstacles will be added at the end of each lesson to facilitate coordination and further increase his postural core strength. During lunging training in good posture, he will be able to sustain equal weight over all four feet and won’t lean from one side to the other. His hind feet will fall into the footprints of the front feet. He will be able to stay in good balance with a consistent rhythm and cadence to all his gaits.

Remember, when engaging in the Hourglass Pattern exercises, do not DRILL. You will only need to work your equine first one direction through the pattern with the designated halts between the cones, cross the diagonal and work in the other direction. Once around the pattern each way is enough to do the job. Work your equine a minimum of once a week and a maximum of once every other day. Be sure to leave a day of rest in between for the best results. Your equine will look forward to his time with you, so make the MOST of it!!

Remember, when engaging in the Hourglass Pattern exercises, do not DRILL. You will only need to work your equine first one direction through the pattern with the designated halts between the cones, cross the diagonal and work in the other direction. Once around the pattern each way is enough to do the job. Work your equine a minimum of once a week and a maximum of once every other day. Be sure to leave a day of rest in between for the best results. Your equine will look forward to his time with you, so make the MOST of it!!

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe and Twitter.

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE, EQUUS REVISITED, my TRAINING MULES & DONKEYS DVD SERIES and A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES at www.luckythreeranchstore.com

© 2013, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

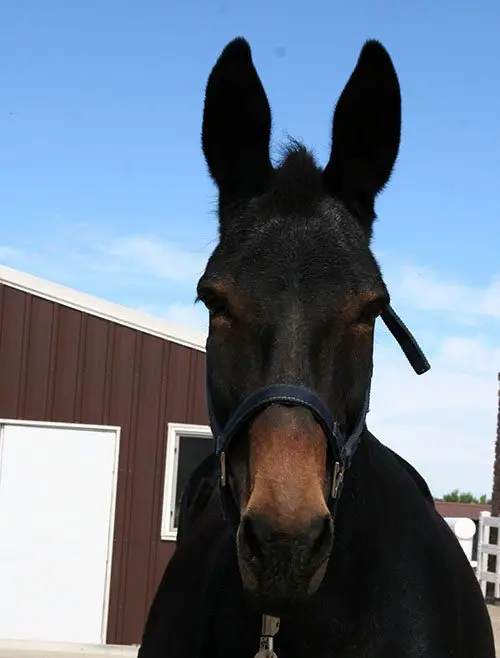

Long before the Founding Fathers drafted our constitution, America began as a religious nation under God, and the mule has his roots in religion just as does the country he has helped to build. The mule of today’s ancestor is the donkey, mentioned in the Bible numerous times as an animal respected by God and blessed by Jesus Christ. The donkey was even chosen to bring Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem and, later, acted as the mount Jesus himself used for his ride into the city of Jerusalem.

Long before the Founding Fathers drafted our constitution, America began as a religious nation under God, and the mule has his roots in religion just as does the country he has helped to build. The mule of today’s ancestor is the donkey, mentioned in the Bible numerous times as an animal respected by God and blessed by Jesus Christ. The donkey was even chosen to bring Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem and, later, acted as the mount Jesus himself used for his ride into the city of Jerusalem. Mules are the true professionals of slapstick humor and professional psychotherapy! When you get into an altercation with a mule, you will seldom get hurt, but you will surely be set straight in a most humiliating way.

Mules are the true professionals of slapstick humor and professional psychotherapy! When you get into an altercation with a mule, you will seldom get hurt, but you will surely be set straight in a most humiliating way.

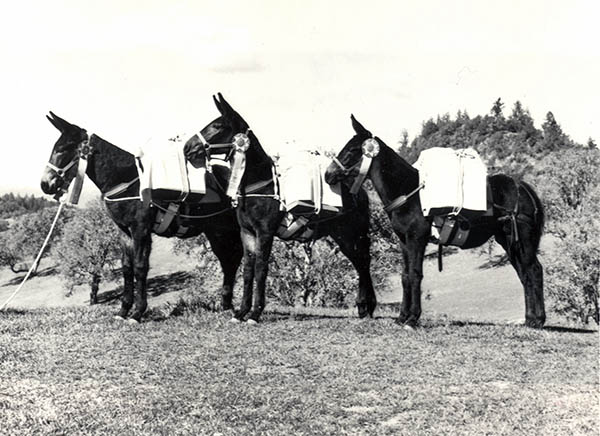

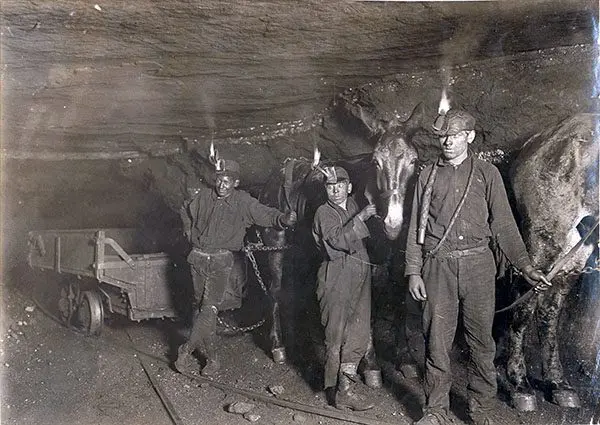

“Mules are the living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West. Mules were the pack animals of Spanish padres and grizzled prospectors. These animals have a dominant place in frontier history. From 1883 to 1889, the 20-mule teams moved 20 million pounds of borax out of Death Valley, California, to Mojave—165 miles away—traveling 15 to 18 miles a day. The 20-mule teams, the dramatic solution of a transportation problem, soon became a world-famous symbol, the trademark first of the Pacific Borax Company and, today, of the many products made by U.S. Borax.” 2 So began the mule’s vital contributions to industry and the economy.

“Mules are the living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West. Mules were the pack animals of Spanish padres and grizzled prospectors. These animals have a dominant place in frontier history. From 1883 to 1889, the 20-mule teams moved 20 million pounds of borax out of Death Valley, California, to Mojave—165 miles away—traveling 15 to 18 miles a day. The 20-mule teams, the dramatic solution of a transportation problem, soon became a world-famous symbol, the trademark first of the Pacific Borax Company and, today, of the many products made by U.S. Borax.” 2 So began the mule’s vital contributions to industry and the economy.

I was born LOVING horses in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1950. I got a pair of chaps and a “bouncing” horse when I was six years old. My Grandmother was always teaching me about Good Posture and Good Manners. She once wanted to take me on a shopping trip to the local mall and requested that I put on one of my frilly dresses. She told me that all the little girls would be wearing them and I flatly refused! You don’t ride horses in frilly dresses! I was a Tom-Boy all the way through! I didn’t want to be a boy, I just wanted to be READY TO RIDE! So, my Grandmother conceded and let me wear my pants! When we got back, she said, “See, I told you all the pretty little girls would be wearing dresses. Now don’t you wish you had worn yours?” “Nope,” I replied and she just shrugged! I still wore my dresses to church!

I was born LOVING horses in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1950. I got a pair of chaps and a “bouncing” horse when I was six years old. My Grandmother was always teaching me about Good Posture and Good Manners. She once wanted to take me on a shopping trip to the local mall and requested that I put on one of my frilly dresses. She told me that all the little girls would be wearing them and I flatly refused! You don’t ride horses in frilly dresses! I was a Tom-Boy all the way through! I didn’t want to be a boy, I just wanted to be READY TO RIDE! So, my Grandmother conceded and let me wear my pants! When we got back, she said, “See, I told you all the pretty little girls would be wearing dresses. Now don’t you wish you had worn yours?” “Nope,” I replied and she just shrugged! I still wore my dresses to church! We moved to California in 1958 when I finally got my first horse, Duchess! I was still very much a Tom Boy now…cleaning stalls, doing chores on the ranch and riding my horse. In 1961, I even joined 4-H and got 4 Hereford cattle. Now I was a REAL Cowgirl!

We moved to California in 1958 when I finally got my first horse, Duchess! I was still very much a Tom Boy now…cleaning stalls, doing chores on the ranch and riding my horse. In 1961, I even joined 4-H and got 4 Hereford cattle. Now I was a REAL Cowgirl!

As we improved our skills, I had seven different mules to school, so I would not just practice one thing over and over. I practiced different disciplines on different days during the week. I never “drilled” on anything, but spent limited time teaching the things I had learned slowly, sequentially and logically. The mules really loved this approach, enjoyed the diversity of the lessons and learned quickly.

As we improved our skills, I had seven different mules to school, so I would not just practice one thing over and over. I practiced different disciplines on different days during the week. I never “drilled” on anything, but spent limited time teaching the things I had learned slowly, sequentially and logically. The mules really loved this approach, enjoyed the diversity of the lessons and learned quickly. Today, the concept of elegance has been greatly compromised by the fast pace of our progressive society. Few of us have neither the time nor the inclination to do what is necessary to cultivate this concept as a major part of our lives. Women today have far too many jobs and responsibilities with which to cope without worrying about being elegant,unless she lives in a densely populated urban area. There are just not a lot of places where a woman can practice being elegant. One of the places she can, however, is in the growing number of Side Saddle classes offered at many of the different Breed Shows across the country. The equestrian art of Side Saddle is currently being revitalized among the different breeds and one of the most enthusiastic groups is our own Longears lovers! But, elegance is not necessarily the only reason our Longears Ladies are riding aside. The lady equestrians of today like to get a more well-rounded education in the art of Horsemanship riding astride,and the perfection of their balanced seat when riding aside only enhances their existing abilities.

Today, the concept of elegance has been greatly compromised by the fast pace of our progressive society. Few of us have neither the time nor the inclination to do what is necessary to cultivate this concept as a major part of our lives. Women today have far too many jobs and responsibilities with which to cope without worrying about being elegant,unless she lives in a densely populated urban area. There are just not a lot of places where a woman can practice being elegant. One of the places she can, however, is in the growing number of Side Saddle classes offered at many of the different Breed Shows across the country. The equestrian art of Side Saddle is currently being revitalized among the different breeds and one of the most enthusiastic groups is our own Longears lovers! But, elegance is not necessarily the only reason our Longears Ladies are riding aside. The lady equestrians of today like to get a more well-rounded education in the art of Horsemanship riding astride,and the perfection of their balanced seat when riding aside only enhances their existing abilities.  Mules can be lovely, obedient and secure Side Saddle mounts when they are brought along correctly, as has been exhibited nationally by Crystal Ward and her mule, Final Legacy. I also fondly remember Ann Hathaway and her Dressage mule, Baby Huey, exhibiting Side Saddle in the Bishop Mule Days parade years ago. I judged the A.D.M.S. Nationals in Austin, Minnesota, and again, I witnessed a sprinkle of elegant Side Saddle riders on mules. In the state of Colorado, there was a surge of Longears Side Saddle riders beginning in 1983. The Side Saddle class for mules at the National Western Stock Show in Denver, Colorado previously had no less than 10 entries in its beginning in 1983, when the mule division was brought back after a long absence from the show.

Mules can be lovely, obedient and secure Side Saddle mounts when they are brought along correctly, as has been exhibited nationally by Crystal Ward and her mule, Final Legacy. I also fondly remember Ann Hathaway and her Dressage mule, Baby Huey, exhibiting Side Saddle in the Bishop Mule Days parade years ago. I judged the A.D.M.S. Nationals in Austin, Minnesota, and again, I witnessed a sprinkle of elegant Side Saddle riders on mules. In the state of Colorado, there was a surge of Longears Side Saddle riders beginning in 1983. The Side Saddle class for mules at the National Western Stock Show in Denver, Colorado previously had no less than 10 entries in its beginning in 1983, when the mule division was brought back after a long absence from the show. Generally speaking, people are quite impressed with the ladies who ride aside, and a common question often arises, “You sure look elegant, but how on earth can you stay on that way?!” We boldly reply, “Our mules teach us and WE LEARN…we are Lady Muleskinners!”

Generally speaking, people are quite impressed with the ladies who ride aside, and a common question often arises, “You sure look elegant, but how on earth can you stay on that way?!” We boldly reply, “Our mules teach us and WE LEARN…we are Lady Muleskinners!” This was demonstrated clearly at a Side Saddle clinic given by Patti Chadwick at the Bitterroot Mule Company in Bennett, Colorado on March 23rd of 1993. Six beginning Side Saddle riders of various equitation skills proved to be quite secure in their seats and no one had any real problems to speak of that day! All levels of riders were jumping cavalletti by the end of the clinic! So you see, it isn’t as insecure as one might be inclined to believe. And with an instructor like Patti Chadwick, it was a snap! The name of the game is “balance,” and whether riding aside on a horse, mule, pony or donkey, it is always a rewarding

This was demonstrated clearly at a Side Saddle clinic given by Patti Chadwick at the Bitterroot Mule Company in Bennett, Colorado on March 23rd of 1993. Six beginning Side Saddle riders of various equitation skills proved to be quite secure in their seats and no one had any real problems to speak of that day! All levels of riders were jumping cavalletti by the end of the clinic! So you see, it isn’t as insecure as one might be inclined to believe. And with an instructor like Patti Chadwick, it was a snap! The name of the game is “balance,” and whether riding aside on a horse, mule, pony or donkey, it is always a rewarding  challenge to finally be able to master this art.

challenge to finally be able to master this art. English Side Saddle is probably the best one in which to learn, since the seat is better balanced over your animal. The Period Side Saddles are the worst, since most are built and balanced incorrectly for our contemporary riders and equines. The older Side Saddles were built to fit the smaller framed riders and larger animals of yesterday, they just don’t fit the conformation of the animals and the size of the ladies of today. Although most Side Saddles today are bought used, there are saddle companies that are making them again due to increased demand. If you buy a Side Saddle, make sure it fits your equine as well as yourself to assure the best ride. There are Vintage Side Saddles from different cultures. Just make sure the tack, equipment and equine match the accessories that you wear. Since Side Saddle is rather unique and there are not a lot of people showing in Side Saddle, the ladies have learned to accept the lax rules around the classes. If they are separated at all, it is usually split into WESTERN SIDE SADDLE and ENGLISH SIDE SADDLE classes.

English Side Saddle is probably the best one in which to learn, since the seat is better balanced over your animal. The Period Side Saddles are the worst, since most are built and balanced incorrectly for our contemporary riders and equines. The older Side Saddles were built to fit the smaller framed riders and larger animals of yesterday, they just don’t fit the conformation of the animals and the size of the ladies of today. Although most Side Saddles today are bought used, there are saddle companies that are making them again due to increased demand. If you buy a Side Saddle, make sure it fits your equine as well as yourself to assure the best ride. There are Vintage Side Saddles from different cultures. Just make sure the tack, equipment and equine match the accessories that you wear. Since Side Saddle is rather unique and there are not a lot of people showing in Side Saddle, the ladies have learned to accept the lax rules around the classes. If they are separated at all, it is usually split into WESTERN SIDE SADDLE and ENGLISH SIDE SADDLE classes. Fitting the Side Saddle to your body is relatively simple. While seated on a chair, measure along the bottom of your thigh from the back of your bent knee to just beyond your hips under your tailbone. The saddle is measured from pommel to cantle and should exceed your leg measurement by no less than two inches. You can ride in a Side Saddle that is a little too large, but not in one that is too small! Consider the width of your saddle to avoid excessive overhang on each side.

Fitting the Side Saddle to your body is relatively simple. While seated on a chair, measure along the bottom of your thigh from the back of your bent knee to just beyond your hips under your tailbone. The saddle is measured from pommel to cantle and should exceed your leg measurement by no less than two inches. You can ride in a Side Saddle that is a little too large, but not in one that is too small! Consider the width of your saddle to avoid excessive overhang on each side.

Side Saddle equines that need a warm-up with a male groom will often use a rigged Two-Sided Side Saddles. He would want to ride aside like the lady would do, but he would need to alter his legs position to exercise the animal in a symmetrical and balanced way. Riding astride a Side Saddle is VERY uncomfortable!

Side Saddle equines that need a warm-up with a male groom will often use a rigged Two-Sided Side Saddles. He would want to ride aside like the lady would do, but he would need to alter his legs position to exercise the animal in a symmetrical and balanced way. Riding astride a Side Saddle is VERY uncomfortable! English Side Saddles are used with a Double Bridle or Pelham Bridles where the reins are carried in a balanced fashion on both sides. You should always have a straight line from your elbow to the bit.

English Side Saddles are used with a Double Bridle or Pelham Bridles where the reins are carried in a balanced fashion on both sides. You should always have a straight line from your elbow to the bit. Place the Side Saddle in the middle of your equine’s back such that you are sitting over the equine’s center of gravity…same as regular saddles. Breast collars are optional (do not use breeching with a Side Saddle). Always keep in mind that your rigging keeps the saddle secure on the back of your equine, so the straps should all be snugly adjusted.

Place the Side Saddle in the middle of your equine’s back such that you are sitting over the equine’s center of gravity…same as regular saddles. Breast collars are optional (do not use breeching with a Side Saddle). Always keep in mind that your rigging keeps the saddle secure on the back of your equine, so the straps should all be snugly adjusted.

Care & Reconditioning of Side Saddle & Tack:

Care & Reconditioning of Side Saddle & Tack:

There was a surge of shows in 1994 featuring mules being ridden Side Saddle in Fox Hunting, Parades, Open Horse Show classes, and Mule Shows, and they have continued to grow nationally. Mules proved their worth as Side Saddle mounts, primarily on the East Coast, California and Colorado!

There was a surge of shows in 1994 featuring mules being ridden Side Saddle in Fox Hunting, Parades, Open Horse Show classes, and Mule Shows, and they have continued to grow nationally. Mules proved their worth as Side Saddle mounts, primarily on the East Coast, California and Colorado!

Horse trainers have kept us in awe of their unique and significant talents for centuries, and now that their techniques are more public, many equine professionals will pooh-pooh those who attempt a “kinder” approach to training. Scientists who study the equine in motion—its nutrition, biomechanics, care and maintenance—have their own perceptions to offer as to what we can learn about equines. Because many of these studies and tests are done in the laboratory, scientists rarely have the opportunity to follow their subjects throughout a lifetime of activity, as well as having the opportunity to experience what it really means for you as a rider, to be in balance with your equine when you work together, whether you are leading, lunging, riding or driving. If they did, their findings would probably yield quite different results. With all this progressive scientific thought, it seems to me that common sense can often get lost in the shuffle and respect for the living creature’s physical, mental and emotional needs may not be met.

Horse trainers have kept us in awe of their unique and significant talents for centuries, and now that their techniques are more public, many equine professionals will pooh-pooh those who attempt a “kinder” approach to training. Scientists who study the equine in motion—its nutrition, biomechanics, care and maintenance—have their own perceptions to offer as to what we can learn about equines. Because many of these studies and tests are done in the laboratory, scientists rarely have the opportunity to follow their subjects throughout a lifetime of activity, as well as having the opportunity to experience what it really means for you as a rider, to be in balance with your equine when you work together, whether you are leading, lunging, riding or driving. If they did, their findings would probably yield quite different results. With all this progressive scientific thought, it seems to me that common sense can often get lost in the shuffle and respect for the living creature’s physical, mental and emotional needs may not be met. degenerative breakdown. For instance, those who get in a hurry in Dressage and do not take a full year at each level in order to develop their equine’s body slowly and methodically may discover, several years later, that their animal has developed ringbone, side bones, arthritis or some other internal malady. These types of injuries and malformations are often not outwardly exhibited until it is too late to do anything about them.

degenerative breakdown. For instance, those who get in a hurry in Dressage and do not take a full year at each level in order to develop their equine’s body slowly and methodically may discover, several years later, that their animal has developed ringbone, side bones, arthritis or some other internal malady. These types of injuries and malformations are often not outwardly exhibited until it is too late to do anything about them.

Tragically, many equines are suffering from abuse every day, while they are trying to please their owners and do what is asked of them. Their owners and trainers take shortcuts that compromise the equine’s health. It could be that these owners and trainers are trying to make choices with limited knowledge and really don’t know whom to believe. But ignorance is not a valid defense and sadly, the animal is the one that ends up suffering.

Tragically, many equines are suffering from abuse every day, while they are trying to please their owners and do what is asked of them. Their owners and trainers take shortcuts that compromise the equine’s health. It could be that these owners and trainers are trying to make choices with limited knowledge and really don’t know whom to believe. But ignorance is not a valid defense and sadly, the animal is the one that ends up suffering. The Lucky Three mules have always been worked in good posture, and spend only as much time on the hot walker as it takes for them to dry after a bath. They maintain their good posture while walking and rarely let the hot walker “pull” them into bad posture.

The Lucky Three mules have always been worked in good posture, and spend only as much time on the hot walker as it takes for them to dry after a bath. They maintain their good posture while walking and rarely let the hot walker “pull” them into bad posture. Like many, I am of the belief that mechanical devices that force an equine into a rounded position do not necessarily put that equine in good posture. I would guess that many trainers think the “Elbow Pull” device that I use is guilty of developing this artificial posture. If that is their opinion, then they do not understand how it works. Rather than pulling the equine’s head down into a submissive position, when adjusted correctly, the “Elbow Pull” acts like a balance bar (like a ballet dancer would use) to help the equine to balance in good posture. It takes time to develop good posture. So, in the beginning, your equine can only sustain good posture for a certain number of measured steps, and then he must “lean” on the “Elbow Pull” in between these moments of sustaining his ideal balance on his own. The “Elbow Pull” simply prevents him from raising his head and neck so high that the neck becomes inverted and the back hollowed, but it does not actually pull his head down. The rope itself is very lightweight and puts virtually no weight on his head and neck at all. Note: Because horses react differently than mules and donkeys when hard-tied, a simple adjustment to allow the “Elbow Pull” to “slip” with a horse is necessary.

Like many, I am of the belief that mechanical devices that force an equine into a rounded position do not necessarily put that equine in good posture. I would guess that many trainers think the “Elbow Pull” device that I use is guilty of developing this artificial posture. If that is their opinion, then they do not understand how it works. Rather than pulling the equine’s head down into a submissive position, when adjusted correctly, the “Elbow Pull” acts like a balance bar (like a ballet dancer would use) to help the equine to balance in good posture. It takes time to develop good posture. So, in the beginning, your equine can only sustain good posture for a certain number of measured steps, and then he must “lean” on the “Elbow Pull” in between these moments of sustaining his ideal balance on his own. The “Elbow Pull” simply prevents him from raising his head and neck so high that the neck becomes inverted and the back hollowed, but it does not actually pull his head down. The rope itself is very lightweight and puts virtually no weight on his head and neck at all. Note: Because horses react differently than mules and donkeys when hard-tied, a simple adjustment to allow the “Elbow Pull” to “slip” with a horse is necessary.

distress and pain. This includes harsh bits, chain leads, twitches, hobbles, stocks and even medications. There are times when our equines can really be a handful, so having a little leverage when needed can be a good thing. However, deciding which equipment to use and learning how to use leverage without it becoming abusive can be a bit daunting. There are so many different types of tack, equipment and restraints that it becomes difficult to determine which would be best to use on your equine to correct a particular problem, or if you really need to use anything at all. It may only be a case of needing to be clearer in your approach, in which case, leverage equipment may not be needed. It is important to make an informed decision when using any leverage equipment to be sure that what you are using is helpful and not abusive.

distress and pain. This includes harsh bits, chain leads, twitches, hobbles, stocks and even medications. There are times when our equines can really be a handful, so having a little leverage when needed can be a good thing. However, deciding which equipment to use and learning how to use leverage without it becoming abusive can be a bit daunting. There are so many different types of tack, equipment and restraints that it becomes difficult to determine which would be best to use on your equine to correct a particular problem, or if you really need to use anything at all. It may only be a case of needing to be clearer in your approach, in which case, leverage equipment may not be needed. It is important to make an informed decision when using any leverage equipment to be sure that what you are using is helpful and not abusive. One very common behavioral problem that seems to identify the need for more leverage is the mule that bolts and runs when on the lead rope. This seems like an obvious disobedience to the handler, and the first thing that comes to mind is to use a lead shank with a chain to gain control of the mule. Normal use for a lead shank is during a Showmanship class at a show and it should rarely be used in training unless the equine will be shown at halter and/or showmanship. And then, training with the lead shank should be done only after the animal is following well through all required movements while in his halter and on a lead rope.

One very common behavioral problem that seems to identify the need for more leverage is the mule that bolts and runs when on the lead rope. This seems like an obvious disobedience to the handler, and the first thing that comes to mind is to use a lead shank with a chain to gain control of the mule. Normal use for a lead shank is during a Showmanship class at a show and it should rarely be used in training unless the equine will be shown at halter and/or showmanship. And then, training with the lead shank should be done only after the animal is following well through all required movements while in his halter and on a lead rope. If, after you’ve employed a kind, considerate and respectful approach along with a food reward, your equine is still being uncooperative, it may be appropriate to use equipment with more leverage such as the “Quick Twist,” but not necessarily chains. Chains do need to be used in some cases, such as with work harness (and most curb bits are now fitted with chains), but when not used correctly, these chains can be abusive. The chains on the pleasure driving harness should clear the legs and heels of the driving equine, and the chin chain on a curb bit should be adjusted so that it is twisted properly and lies flat against the animal’s jaw with an allowance of two fingers between the chain and the jaw, thereby minimizing any chance of injury. If you have a generally compliant equine, it is better to use a leather chin strap on your curb bit rather than a chain.

If, after you’ve employed a kind, considerate and respectful approach along with a food reward, your equine is still being uncooperative, it may be appropriate to use equipment with more leverage such as the “Quick Twist,” but not necessarily chains. Chains do need to be used in some cases, such as with work harness (and most curb bits are now fitted with chains), but when not used correctly, these chains can be abusive. The chains on the pleasure driving harness should clear the legs and heels of the driving equine, and the chin chain on a curb bit should be adjusted so that it is twisted properly and lies flat against the animal’s jaw with an allowance of two fingers between the chain and the jaw, thereby minimizing any chance of injury. If you have a generally compliant equine, it is better to use a leather chin strap on your curb bit rather than a chain. To employ the “Quick Twist” restraint, just take your lead rope and create a loop and feed it through the noseband of your nylon halter (rope halters are too loose and do not work) from back to front and then over the mule’s nose. When you pull on the rope, it will tighten around the end of the his nose below the incisive bones and over the cartilage, making breathing just a little difficult. Don’t keep pulling—just stand quietly and hold the tension snug. Let the equine come forward to you and slacken the rope himself by coming forward and allowing a free flow of air through his nostrils. Then, if the mule does not follow, just walk a step or two, creating tension on the rope, and then stand still again. When he does come forward, stop long enough to reward him with the oats reward before you proceed forward again. Keep the lead rope short and stand still in a balanced way so he cannot get ahead of you and jerk you off your feet. If you are standing still in a balanced position, it will be difficult for him to jerk the lead rope from your hand and leave.

To employ the “Quick Twist” restraint, just take your lead rope and create a loop and feed it through the noseband of your nylon halter (rope halters are too loose and do not work) from back to front and then over the mule’s nose. When you pull on the rope, it will tighten around the end of the his nose below the incisive bones and over the cartilage, making breathing just a little difficult. Don’t keep pulling—just stand quietly and hold the tension snug. Let the equine come forward to you and slacken the rope himself by coming forward and allowing a free flow of air through his nostrils. Then, if the mule does not follow, just walk a step or two, creating tension on the rope, and then stand still again. When he does come forward, stop long enough to reward him with the oats reward before you proceed forward again. Keep the lead rope short and stand still in a balanced way so he cannot get ahead of you and jerk you off your feet. If you are standing still in a balanced position, it will be difficult for him to jerk the lead rope from your hand and leave. Restraints should not be used as a means to control your animal except for a short period of time with the purpose of showing them a correct behavior. Restraints should be used as a support and not a controlling device. Restraints should be “phased out” as soon as possible.

Restraints should not be used as a means to control your animal except for a short period of time with the purpose of showing them a correct behavior. Restraints should be used as a support and not a controlling device. Restraints should be “phased out” as soon as possible. Do not try to bully him into it or he will just pull back. This should be done while he is standing parallel to the hitch rail so that when you pull the rope tight, it pulls his head tightly sideways to the hitch rail. This will keep him from being able to swing his rear end around to block you. Reward him with oats and let him quiet down in this restraint before approaching with your shot. If he manages to keep you off the clear side, you can always go to the other side of the hitch rail and give him the shot from that side without fear of injury. You can do this along a stout fence provided the rails are sturdy. If you do this correctly, it will simply restrain him in a safe manner and keep you out of the line of fire. Each new time that you give shots, try to do it with the rope a little looser each time to fade out the restraint. They will usually just come to expect and go for their position along the hitch rail or fence and will lean into it like they do when you first gave the shots like this. He will soon learn to quiet down immediately when his face is being tied and at best will seem to be saying, “Dang, do we have to do this again?!” But, he will learn to comply.

Do not try to bully him into it or he will just pull back. This should be done while he is standing parallel to the hitch rail so that when you pull the rope tight, it pulls his head tightly sideways to the hitch rail. This will keep him from being able to swing his rear end around to block you. Reward him with oats and let him quiet down in this restraint before approaching with your shot. If he manages to keep you off the clear side, you can always go to the other side of the hitch rail and give him the shot from that side without fear of injury. You can do this along a stout fence provided the rails are sturdy. If you do this correctly, it will simply restrain him in a safe manner and keep you out of the line of fire. Each new time that you give shots, try to do it with the rope a little looser each time to fade out the restraint. They will usually just come to expect and go for their position along the hitch rail or fence and will lean into it like they do when you first gave the shots like this. He will soon learn to quiet down immediately when his face is being tied and at best will seem to be saying, “Dang, do we have to do this again?!” But, he will learn to comply. This is a humane restraint for mules and donkeys, but do not try this with a horse! This is a good restraint to use (and fade out) for any Longears that is difficult to worm, give shots, take blood, clip bridle paths and to use for those that are difficult to bridle. When using the Face Tie for bridling training (or clipping the bridle path), you will only need to go through the noseband and hitch rail (and not through the throatlatch unless you need to prevent them from turning into you). Just make sure when you put on the bridle that you “protect” their sensitive ears with your hands as it goes on and they will learn to trust you. Put the bridle on over the halter for the lessons until they don’t mind the bridling process.

This is a humane restraint for mules and donkeys, but do not try this with a horse! This is a good restraint to use (and fade out) for any Longears that is difficult to worm, give shots, take blood, clip bridle paths and to use for those that are difficult to bridle. When using the Face Tie for bridling training (or clipping the bridle path), you will only need to go through the noseband and hitch rail (and not through the throatlatch unless you need to prevent them from turning into you). Just make sure when you put on the bridle that you “protect” their sensitive ears with your hands as it goes on and they will learn to trust you. Put the bridle on over the halter for the lessons until they don’t mind the bridling process. Your Longears will only need the kicking training covered in

Your Longears will only need the kicking training covered in  the hind foot, around the pastern and let it lay on the floor. Next time, you won’t have to use it at all. Your goal is to phase out the restraint entirely.

the hind foot, around the pastern and let it lay on the floor. Next time, you won’t have to use it at all. Your goal is to phase out the restraint entirely. Hobbles are another form of leverage equipment and there are many different kinds of hobbles for different purposes. The hobbles that have chains on them should be avoided, as the equine can become entangled and the chains can do damage to their legs. Thin leather hobbles or coarse rope can chafe the hair right off the skin around the pastern and can cause severe abrasions that may never heal. Thick leather hobbles are best, as they will break when under extreme stress, releasing before damage to the equine is done. If so inclined, all mules and some horses can gallop in hobbles, so hobbles really aren’t all that effective for leverage. Tying onto a hyline (a rope suspended high between two trees that acts as a hitching line for overnighting equines in the mountains) is a better choice, and if the horses are tied, then the mules should not have to be tied or hobbled because they will generally stay with the horses. Personally, I only use hobbles in a controlled situation at the work station when body clipping my equine’s legs for show.

Hobbles are another form of leverage equipment and there are many different kinds of hobbles for different purposes. The hobbles that have chains on them should be avoided, as the equine can become entangled and the chains can do damage to their legs. Thin leather hobbles or coarse rope can chafe the hair right off the skin around the pastern and can cause severe abrasions that may never heal. Thick leather hobbles are best, as they will break when under extreme stress, releasing before damage to the equine is done. If so inclined, all mules and some horses can gallop in hobbles, so hobbles really aren’t all that effective for leverage. Tying onto a hyline (a rope suspended high between two trees that acts as a hitching line for overnighting equines in the mountains) is a better choice, and if the horses are tied, then the mules should not have to be tied or hobbled because they will generally stay with the horses. Personally, I only use hobbles in a controlled situation at the work station when body clipping my equine’s legs for show. I do not approve of using power tools on the equine’s hooves at all. In order for the equine’s body to be properly balanced in good posture, the hooves must first be properly balanced. Power tools cannot possibly shape the hoof with proper curvature in the sole, alignment of angles and equal balance over the hoof walls with appropriate pressure to the heels and frog.

I do not approve of using power tools on the equine’s hooves at all. In order for the equine’s body to be properly balanced in good posture, the hooves must first be properly balanced. Power tools cannot possibly shape the hoof with proper curvature in the sole, alignment of angles and equal balance over the hoof walls with appropriate pressure to the heels and frog.

Since a donkey can become quite stubborn when treated poorly, it is important that you take the time to help your child and donkey get started properly. Even an untried donkey, with proper help, can be a wonderful mount for a child. In the first few weeks together, the child and donkey should simply spend quality time getting to know each other. Teach your child the correct way to handle and groom the donkey. The personal bond between them will develop on its own. This is also a good way to start with mules.

Since a donkey can become quite stubborn when treated poorly, it is important that you take the time to help your child and donkey get started properly. Even an untried donkey, with proper help, can be a wonderful mount for a child. In the first few weeks together, the child and donkey should simply spend quality time getting to know each other. Teach your child the correct way to handle and groom the donkey. The personal bond between them will develop on its own. This is also a good way to start with mules. When your child and donkey have developed confidence in each other, you can begin to teach them the fundamentals of riding. Tack up the donkey in a small saddle suitable for his size and a snaffle bridle and then take him to a small pen to work on the lunge line. Allow your child to sit astride the donkey as he walks around you. Explain to you child the basics of turning and stopping with the direct snaffle rein contact, commonly called “plow-reining.” be sure to instruct the child not to pull hard, or jerk the reins. Donkeys have very sensitive mouths and do not respond well when they are in pain.

When your child and donkey have developed confidence in each other, you can begin to teach them the fundamentals of riding. Tack up the donkey in a small saddle suitable for his size and a snaffle bridle and then take him to a small pen to work on the lunge line. Allow your child to sit astride the donkey as he walks around you. Explain to you child the basics of turning and stopping with the direct snaffle rein contact, commonly called “plow-reining.” be sure to instruct the child not to pull hard, or jerk the reins. Donkeys have very sensitive mouths and do not respond well when they are in pain. Love and caresses are an excellent reward and the reward of crimped oats certainly does no harm, but tell the child to keep his hands flat so the donkey doesn’t accidently get his fingers! Donkeys are very appreciative animals. If the child and donkey are supervised correctly, it can greatly enhance the entire riding experience. The donkey will protect your child with his excellent judgment and the child will learn to be a patient and understanding person through the interaction with his donkey. The reason is simple: donkeys will not respond unless treated fairly. Many an equestrian in Great Britain has spent his early years astride a donkey and have become better riders because of it! So, if your child expresses an interest in riding, consider starting him with a donkey gelding, or maybe even a jennet. Besides being patient with children, his size is more suitable, he has ample strength to carry children and is an easy keeper, so feed and vet bills can usually be kept to a minimum.

Love and caresses are an excellent reward and the reward of crimped oats certainly does no harm, but tell the child to keep his hands flat so the donkey doesn’t accidently get his fingers! Donkeys are very appreciative animals. If the child and donkey are supervised correctly, it can greatly enhance the entire riding experience. The donkey will protect your child with his excellent judgment and the child will learn to be a patient and understanding person through the interaction with his donkey. The reason is simple: donkeys will not respond unless treated fairly. Many an equestrian in Great Britain has spent his early years astride a donkey and have become better riders because of it! So, if your child expresses an interest in riding, consider starting him with a donkey gelding, or maybe even a jennet. Besides being patient with children, his size is more suitable, he has ample strength to carry children and is an easy keeper, so feed and vet bills can usually be kept to a minimum. and will generally get his disposition from the mare. So, if you wish to get a mule for your child, make sure it is an individual with a quiet disposition. Then you can consider such things as size, color and other traits. Be advised that mini mules can be very strong and hyperactive with alpha personalities. IN some cases it might be better to get a larger, quieter mule for your child. The right mule can be just as good a babysitter as the right donkey, and usually more reliable than any horse!

and will generally get his disposition from the mare. So, if you wish to get a mule for your child, make sure it is an individual with a quiet disposition. Then you can consider such things as size, color and other traits. Be advised that mini mules can be very strong and hyperactive with alpha personalities. IN some cases it might be better to get a larger, quieter mule for your child. The right mule can be just as good a babysitter as the right donkey, and usually more reliable than any horse! When you are tacking up your equine, stay in close to put on the saddle and bridle, but when walking around and behind them, give them a wide berth out of kicking range. Give the child detailed lessons on how to bridle and saddle the equine without hurting him, around the ears, eyes, etc. and never use the ears to hold his head still! Teach the child to WALK around equines and not run, or be abrupt, in their movements. Get your child a saddle that they can feel secure in, that has stirrups that will adjust to their short legs, or an alternate set of stirrups that will fit onto an adult saddle for them.

When you are tacking up your equine, stay in close to put on the saddle and bridle, but when walking around and behind them, give them a wide berth out of kicking range. Give the child detailed lessons on how to bridle and saddle the equine without hurting him, around the ears, eyes, etc. and never use the ears to hold his head still! Teach the child to WALK around equines and not run, or be abrupt, in their movements. Get your child a saddle that they can feel secure in, that has stirrups that will adjust to their short legs, or an alternate set of stirrups that will fit onto an adult saddle for them. Children and donkeys, or mules, have not been together much in this country in the recent past. Perhaps it is because we have not given children a chance to show their Longears publicly. Realizing this need, as in horse shows, youth classes have been included in the Longears shows of today to encourage our youth to take an active interest in the promotion of Longears. The jobs these “kids” are dong with their mules and donkeys are wonderful and their contributions are extensive. The values learned by children when dealing with donkeys and mules will stand them in good stead throughout their lives, not to mention the joy they will discover in having such an interactive and affectionate companion.

Children and donkeys, or mules, have not been together much in this country in the recent past. Perhaps it is because we have not given children a chance to show their Longears publicly. Realizing this need, as in horse shows, youth classes have been included in the Longears shows of today to encourage our youth to take an active interest in the promotion of Longears. The jobs these “kids” are dong with their mules and donkeys are wonderful and their contributions are extensive. The values learned by children when dealing with donkeys and mules will stand them in good stead throughout their lives, not to mention the joy they will discover in having such an interactive and affectionate companion.

With the introduction of the automobile came decreased interest in horse-drawn vehicles. Tractors replaced equine-driven vehicles in the fields. It seemed as if equines had been put out of a job! But, as with any change, this was only temporary. Modern society still has need of equine participation, especially from donkeys and mules. The well-schooled driving donkey or mule is much safer and more reliable than any horse. The reason for this is the donkey and mules’ natural sensibility and their positive response to verbal communication. Once they have learned the parameters of their job, if treated fairly, they will calmly and diligently go about their business, flicking their ears back and forth toward the driver, always listening for verbal reinforcement of their behavior. In a pinch, they can more often be prevented from “freaking out” with a few calm and reassuring words. Their strength and durability enables them to work longer and harder hours than can a horse and their variety of sizes and colors provides them as suitable driving animals for a number of driving-related activities.