MULE CROSSING: Mules and Dressage

By Meredith Hodges

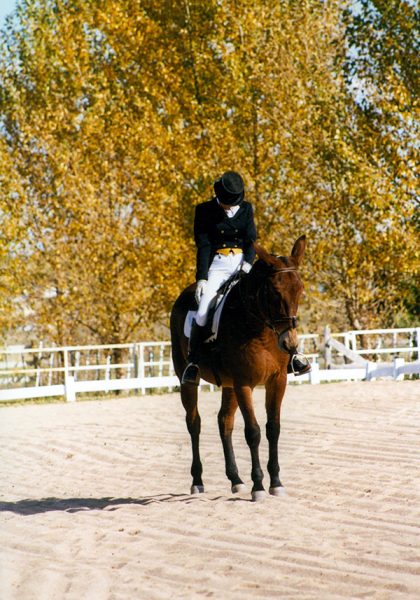

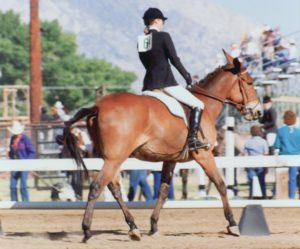

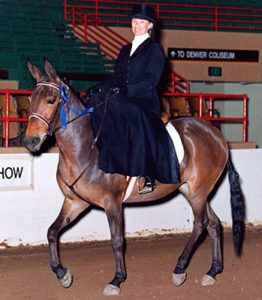

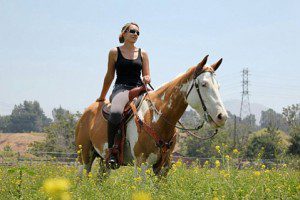

It is no secret that the popularity of mules in this country is on the rise and their uses are quite varied. Many people believed that mules were used solely for packing and pulling, but modern-day mule lovers have competed successfully with mules in all areas of equine athletics, exhibiting the mules’ true abilities and versatility. Western style riders were the first to catch on to mules, but English riders soon followed suit. Perhaps the most elite form of English riding, Dressage was avoided for many years. There could have been any number of reasons for this, however, an adventurous lady from Montana chose to train her more than 16 hand mule, Baby Huey, for Dressage and competed successfully in many shows. This opened still another door for mules.

It is no secret that the popularity of mules in this country is on the rise and their uses are quite varied. Many people believed that mules were used solely for packing and pulling, but modern-day mule lovers have competed successfully with mules in all areas of equine athletics, exhibiting the mules’ true abilities and versatility. Western style riders were the first to catch on to mules, but English riders soon followed suit. Perhaps the most elite form of English riding, Dressage was avoided for many years. There could have been any number of reasons for this, however, an adventurous lady from Montana chose to train her more than 16 hand mule, Baby Huey, for Dressage and competed successfully in many shows. This opened still another door for mules.

The object of Dressage is “the harmonious development of the physique and ability of the horse. As a result, it makes the horse calm, supple, loose, and flexible, but also confident, attentive and keen, thus achieving perfect understanding with his rider.” In Dressage, one is not concerned with time in training. Rather, it is measured in progress from one step to another. Dressage requires a discipline of the mind and body. This slow and methodical way of training lends itself nicely to mules.

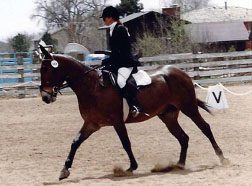

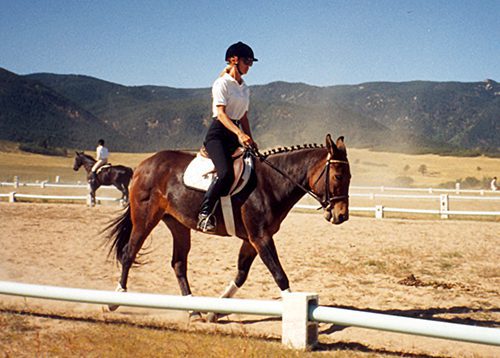

One of the basic differences between training mules and training horses is the essential maintenance of a calm attitude by the trainer. Mules will not respond positively to a bad temper. The calmer and more deliberate the trainer, the more responsive the mule. Training in this manner will reveal the true abilities of the animal. His paces will be free and regular and his movements will be harmonious, light, and easy. Impulsion from the hindquarters is reflected by lightness on the forehand with quiet acceptance of the bridle with no tenseness or resistance. An animal trained in Dressage will appear to be doing of his own accord what is required with an air of confidence and always attentive. The walk is regular and free, and unconstrained. The trot is free, supple, regular, sustained and active. The canter is united, light and cadenced. These all reflect active and animation of the four quarters. He is never sluggish. He will respond to the slightest cue from the rider and thereby, give life and spirit to rest of his body. In all his work, a Dressage animal will be “on the bit” with a light, soft contact and submissiveness throughout. Many good trainers use these basic principles in turning out their best-trained animals. It just doesn’t always get labeled as “Dressage”.

One of the basic differences between training mules and training horses is the essential maintenance of a calm attitude by the trainer. Mules will not respond positively to a bad temper. The calmer and more deliberate the trainer, the more responsive the mule. Training in this manner will reveal the true abilities of the animal. His paces will be free and regular and his movements will be harmonious, light, and easy. Impulsion from the hindquarters is reflected by lightness on the forehand with quiet acceptance of the bridle with no tenseness or resistance. An animal trained in Dressage will appear to be doing of his own accord what is required with an air of confidence and always attentive. The walk is regular and free, and unconstrained. The trot is free, supple, regular, sustained and active. The canter is united, light and cadenced. These all reflect active and animation of the four quarters. He is never sluggish. He will respond to the slightest cue from the rider and thereby, give life and spirit to rest of his body. In all his work, a Dressage animal will be “on the bit” with a light, soft contact and submissiveness throughout. Many good trainers use these basic principles in turning out their best-trained animals. It just doesn’t always get labeled as “Dressage”.

One need only try to bully a mule once to find out that it simply doesn’t work. The mule, with the strength of the jack, can crook his neck so that no amount of pull can cause him to bend and the wide opening of the mouth leaves you pulling on virtual “rubber!” Consequently, you are left doing primarily what he wants. Slow and methodical training in Dressage can unite a mule and rider in a beautiful, flawless picture. Communication between equine and rider is, after all, what Dressage is all about.

One need only try to bully a mule once to find out that it simply doesn’t work. The mule, with the strength of the jack, can crook his neck so that no amount of pull can cause him to bend and the wide opening of the mouth leaves you pulling on virtual “rubber!” Consequently, you are left doing primarily what he wants. Slow and methodical training in Dressage can unite a mule and rider in a beautiful, flawless picture. Communication between equine and rider is, after all, what Dressage is all about.

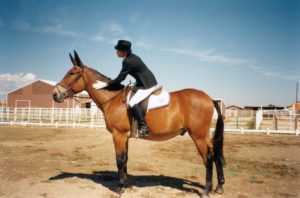

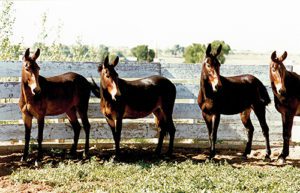

O.K., you say. So the mule lends itself well to this type of training, but what of his tendency toward possessing naturally attractive gaits and a smooth way of moving? That’s simple. A mule is always better than the horse out of which he came. Should you desire a particular kind of action, seek a mule out of a mare that possesses that particular trait. The primarily smooth muscling of the mule allows him to be somewhat of a ballet dancer among equines. His gait is generally smoother than most horses anyway, with the strength to control his movements as is exhibited by his unique ability to jump from a standstill. Certainly, he could conceivably perform the more intricate movements of advanced Dressage.

There are those who believe that mules are just not as pretty as horses, and therefore, could not be as beautiful to watch in Dressage. Naturally, there are mules that would not be suitable for this form of training for the show ring, but so there are also unsuitable horses. With selective breeding, there have emerged mules that do possess a certain beauty with their grace and agility. In some cases, it is difficult to distinguish them from fine horses.

The mule, as anything but a packing and pulling animal, has not been tried too much in the past. This is why they have not been seen in many places of equine athletics. Mule lovers today are trying mules in all areas of equine sports and are exhibiting that mules can do it all! With the intense training and showing of more mules, more of the uneducated public is able to see that there is far more to mules than was portrayed in the past. Horsemen are continually surprised and amazed… and in some cases, even converted to mules!

The mule, as anything but a packing and pulling animal, has not been tried too much in the past. This is why they have not been seen in many places of equine athletics. Mule lovers today are trying mules in all areas of equine sports and are exhibiting that mules can do it all! With the intense training and showing of more mules, more of the uneducated public is able to see that there is far more to mules than was portrayed in the past. Horsemen are continually surprised and amazed… and in some cases, even converted to mules!

As more is discovered about these marvelous animals, more people become attracted to them. Discovering mules is something like exploring unchartered territory: the possibilities are endless. As in any new venture, it takes a while for the word to get out, but it is clear that in this country the word is out and the popularity of mules is increasing with each new discovery about them. Perhaps, in the future, the public will be able to witness the first mule doing a “Capriole!”

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE and EQUUS REVISITED at www.luckythreeranchstore.com.

© 1986, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

By Meredith Hodges

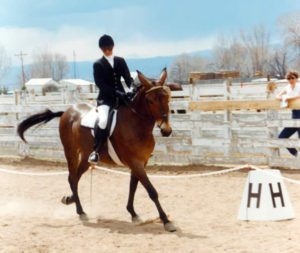

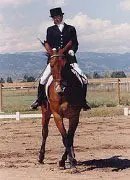

By Meredith Hodges Dressage is practiced in an arena marked by a low fence with letters at strategic intervals. A manual outlining the different “tests” tells you what to do and where to go in your marked arena. Once an animal is started under saddle, he begins dressage training at what is called Training Level. There are four tests at each level that increase ever so slightly in difficulty from one to the next. In each level there are certain objectives to be met. At Training Level, for instance, your mule should learn to travel in straight lines and to bend his body to the arc of large circles and in corners, and to make upward and downward transitions through his gaits while maintaining good balance, a steady rhythm and cadence throughout the test in an elongated and elastic frame. At the same time, the rider is also learning and conditioning his own body to react appropriately to the body of his animal. The objective of dressage training is to develop a harmonious balance and understanding between equine and rider physically and mentally.

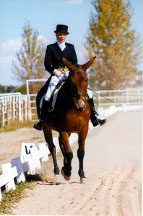

Dressage is practiced in an arena marked by a low fence with letters at strategic intervals. A manual outlining the different “tests” tells you what to do and where to go in your marked arena. Once an animal is started under saddle, he begins dressage training at what is called Training Level. There are four tests at each level that increase ever so slightly in difficulty from one to the next. In each level there are certain objectives to be met. At Training Level, for instance, your mule should learn to travel in straight lines and to bend his body to the arc of large circles and in corners, and to make upward and downward transitions through his gaits while maintaining good balance, a steady rhythm and cadence throughout the test in an elongated and elastic frame. At the same time, the rider is also learning and conditioning his own body to react appropriately to the body of his animal. The objective of dressage training is to develop a harmonious balance and understanding between equine and rider physically and mentally. When your equine is strong, steady, rhythmic, and responsive at Training Level, he can then proceed to the next level, or First Level. At First Level, he learns to initiate more engagement of the hindquarters (collection) and begins to condition the muscles needed for lateral work through lengthening of the gaits and yielding from the leg. As he is better conditioned in his body, he is better able to perform and hold the balance and collection that is needed for Second Level, then Third Level, Fourth Level, and beyond. In order to gain true collection, he needs to possess incredible strength, such that he can step underneath himself with power from his hindquarters, round his back, and bring lightness and suppleness to the front end. This kind of posture makes the fancy upper level movements one usually associates with Dressage fluid and effortless with no apparent movement by the rider.

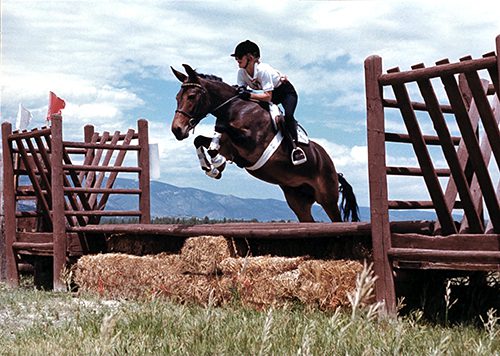

When your equine is strong, steady, rhythmic, and responsive at Training Level, he can then proceed to the next level, or First Level. At First Level, he learns to initiate more engagement of the hindquarters (collection) and begins to condition the muscles needed for lateral work through lengthening of the gaits and yielding from the leg. As he is better conditioned in his body, he is better able to perform and hold the balance and collection that is needed for Second Level, then Third Level, Fourth Level, and beyond. In order to gain true collection, he needs to possess incredible strength, such that he can step underneath himself with power from his hindquarters, round his back, and bring lightness and suppleness to the front end. This kind of posture makes the fancy upper level movements one usually associates with Dressage fluid and effortless with no apparent movement by the rider. Each level builds on the exercises from the previous level from Training through Intermediate to Prix St. George and Grand Prix. Combined Training is the addition of gymnastic-type exercises (aerobic equivalent) to the regular dressage routine. The jumping, or gymnastic, exercises can start in conjunction with the dressage tests as early as Training Level and can greatly enhance and improve their Dressage performances. It gives the equine a mental break from the repetition and intensity of the dressage tests. It allows the animal to develop better coordination and stronger forward movement. Jumping also enhances hindquarter development and the variety in routine keeps your equine’s mind fresh, alert, and willing to perform.

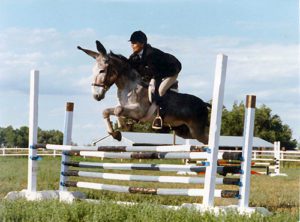

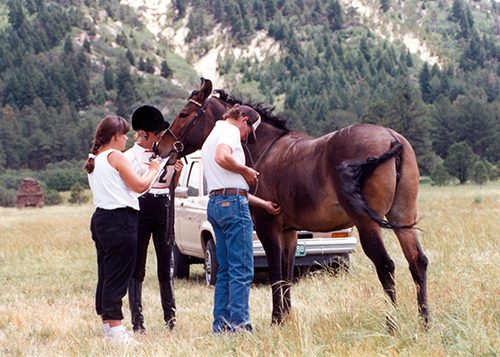

Each level builds on the exercises from the previous level from Training through Intermediate to Prix St. George and Grand Prix. Combined Training is the addition of gymnastic-type exercises (aerobic equivalent) to the regular dressage routine. The jumping, or gymnastic, exercises can start in conjunction with the dressage tests as early as Training Level and can greatly enhance and improve their Dressage performances. It gives the equine a mental break from the repetition and intensity of the dressage tests. It allows the animal to develop better coordination and stronger forward movement. Jumping also enhances hindquarter development and the variety in routine keeps your equine’s mind fresh, alert, and willing to perform. All the Lucky Three mules will attest to the success of Dressage and Combined Training, particularly Lucky Three Mae Bea C.T., who began to do exercises at the more advanced levels. Before we began dressage training, we were training for each event. With dressage training she developed an incredible responsiveness to seat, leg and rein cues and was able to perform anything easily and willingly. She did absolutely everything you would ask of her and did it all with above average quality and enthusiasm. It has made classes in which she already excelled even better! The other Lucky Three mules exhibited this same above-average attitude and performance across the board with Dressage and Combined Training. This kind of variety keeps life interesting and challenging as we find new uses and events in which we can compete our mules. They have even made their own unique contribution to the equine industry! Volunteers to help set up shows and events are often hard to find.

All the Lucky Three mules will attest to the success of Dressage and Combined Training, particularly Lucky Three Mae Bea C.T., who began to do exercises at the more advanced levels. Before we began dressage training, we were training for each event. With dressage training she developed an incredible responsiveness to seat, leg and rein cues and was able to perform anything easily and willingly. She did absolutely everything you would ask of her and did it all with above average quality and enthusiasm. It has made classes in which she already excelled even better! The other Lucky Three mules exhibited this same above-average attitude and performance across the board with Dressage and Combined Training. This kind of variety keeps life interesting and challenging as we find new uses and events in which we can compete our mules. They have even made their own unique contribution to the equine industry! Volunteers to help set up shows and events are often hard to find. The Mountain States Combined Training Association is grateful to the Lucky Three Ranch, but particularly to Mae Bea C.T. for her help in dragging logs to help build cross country jumps at Lory State Park in Fort Collins, Colorado. Mae Bea C.T., trained in Dressage and Combined Training, not only jumps those cross-country jumps, but helps to build them as well! She is a strong, healthy and willing mule thanks to the preservation of a 100-year-old or more equestrian art called Dressage!

The Mountain States Combined Training Association is grateful to the Lucky Three Ranch, but particularly to Mae Bea C.T. for her help in dragging logs to help build cross country jumps at Lory State Park in Fort Collins, Colorado. Mae Bea C.T., trained in Dressage and Combined Training, not only jumps those cross-country jumps, but helps to build them as well! She is a strong, healthy and willing mule thanks to the preservation of a 100-year-old or more equestrian art called Dressage!

By Meredith Hodges

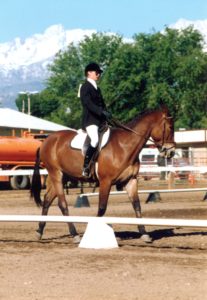

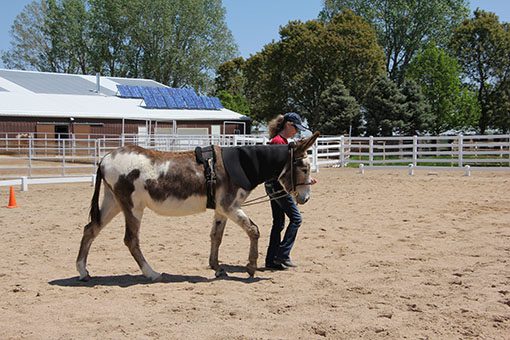

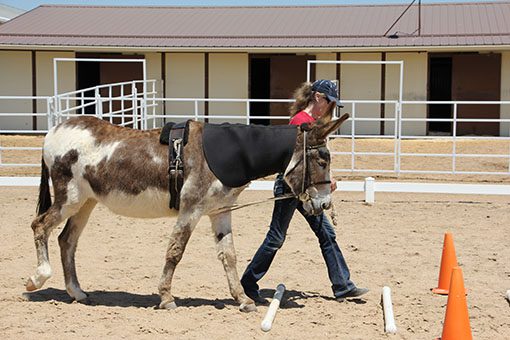

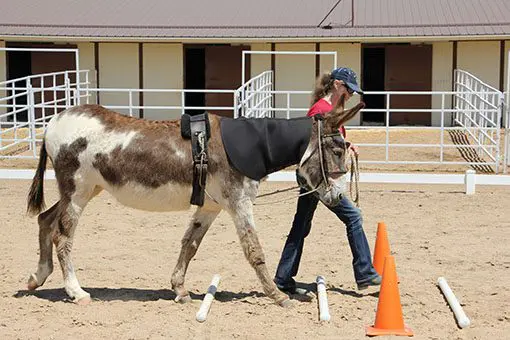

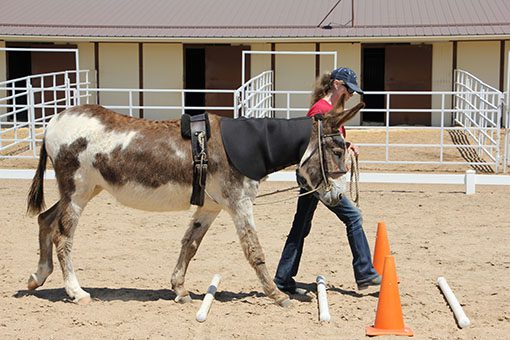

By Meredith Hodges Competitive riding requires constant discipline and dedication to lessons, clinics, shows, and practice sessions for the purpose of conditioning the bodies of mules and riders to perform what is learned. In turn, that which is put before the public is continually more impressive in the quest for perfection. As mules and riders meet new challenges, the appeal of the animal itself is broadened and becomes more positive.

Competitive riding requires constant discipline and dedication to lessons, clinics, shows, and practice sessions for the purpose of conditioning the bodies of mules and riders to perform what is learned. In turn, that which is put before the public is continually more impressive in the quest for perfection. As mules and riders meet new challenges, the appeal of the animal itself is broadened and becomes more positive. C.D.M.S meeting are held every two weeks at the Lucky Three Ranch in Loveland, Colorado. Members arrive at about noon and spend two to three hours in a video-taped group lesson and practice session after which is a supper meeting. During the meeting, our video-taped session is evaluated and critiqued and each rider is given his riding and training assignment. Club business is then discussed and the meeting adjourns.

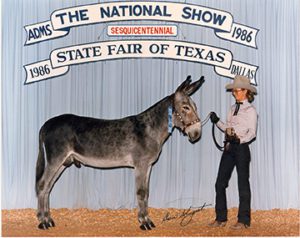

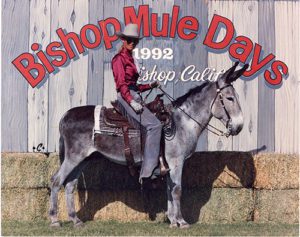

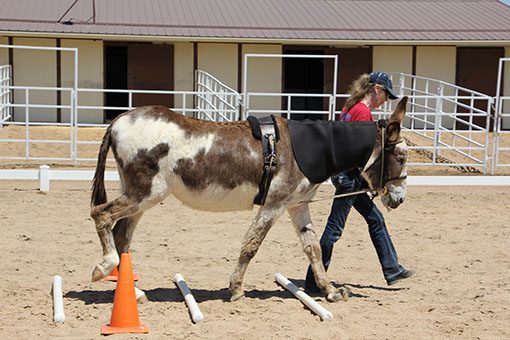

C.D.M.S meeting are held every two weeks at the Lucky Three Ranch in Loveland, Colorado. Members arrive at about noon and spend two to three hours in a video-taped group lesson and practice session after which is a supper meeting. During the meeting, our video-taped session is evaluated and critiqued and each rider is given his riding and training assignment. Club business is then discussed and the meeting adjourns. C.D.M.S. is not just for mules. We support and appreciate the donkey and his contribution to this industry. We recognize the importance of Donkey Power! We hope that as we grow as a society, we can establish an equally fun and interesting program for our donkeys. The World Champion Mule Show at Bishop, California, held in May recognized this need and a “Donkey Driving” class was added to their schedule. In Colorado, we have had limited donkey halter classes and driving classes. We hope to add to these. At the Queen City Donkey & Mule Show (July 30-Aug. 2), we added a Wild Burro Halter class. We hope this will help to promote the adoption and care of these beloved animals. The driving classes are split according to size and we hope to see more donkeys in the smaller sections. If enough donkeys show, we will be able to break off an exclusive Donkey Driving class and eventually add Donkey Trail, Pack Trail and Donkey Pleasure. Please help support our donkeys!

C.D.M.S. is not just for mules. We support and appreciate the donkey and his contribution to this industry. We recognize the importance of Donkey Power! We hope that as we grow as a society, we can establish an equally fun and interesting program for our donkeys. The World Champion Mule Show at Bishop, California, held in May recognized this need and a “Donkey Driving” class was added to their schedule. In Colorado, we have had limited donkey halter classes and driving classes. We hope to add to these. At the Queen City Donkey & Mule Show (July 30-Aug. 2), we added a Wild Burro Halter class. We hope this will help to promote the adoption and care of these beloved animals. The driving classes are split according to size and we hope to see more donkeys in the smaller sections. If enough donkeys show, we will be able to break off an exclusive Donkey Driving class and eventually add Donkey Trail, Pack Trail and Donkey Pleasure. Please help support our donkeys!

Over the past few decades, through trial and error, we equine owners and trainers have discovered that, when communicating with our equines, harsh bits are not really necessary. Rather, it is safer and more beneficial to use milder tack and equipment, to concentrate on learning correct body language and to give clear cues with our hands, seat and legs to elicit the desired response from our equines.

Over the past few decades, through trial and error, we equine owners and trainers have discovered that, when communicating with our equines, harsh bits are not really necessary. Rather, it is safer and more beneficial to use milder tack and equipment, to concentrate on learning correct body language and to give clear cues with our hands, seat and legs to elicit the desired response from our equines. When it comes to rider/equine communication, bitless and/or brideless techniques do not work as well as the simple, direct rein action of the snaffle bit in concert with your seat and legs.Many people are under the impression that having a bit in the mouth is painful for an equine, and the seeming “nutcracker” action of the snaffle bit when it is in your hands suggests that it might pinch your animal’s tongue when you pull on the reins. The mouthpiece of the snaffle bit actually “breaks” in the middle, allowing it to slide easily across the top of your equine’s tongue. It does not pinch his tongue, but it does put pressure on the corners of his mouth. The snaffle bit is correctly defined as a bit that promotes “direct rein action,” meaning that when you pull right, you go right and when you pull left, you go left. A snaffle bit does not have a shank. If it did have a shank, it would be considered a curb bit, regardless of how short the shank really is (as is the case with a Tom Thumb bit).

When it comes to rider/equine communication, bitless and/or brideless techniques do not work as well as the simple, direct rein action of the snaffle bit in concert with your seat and legs.Many people are under the impression that having a bit in the mouth is painful for an equine, and the seeming “nutcracker” action of the snaffle bit when it is in your hands suggests that it might pinch your animal’s tongue when you pull on the reins. The mouthpiece of the snaffle bit actually “breaks” in the middle, allowing it to slide easily across the top of your equine’s tongue. It does not pinch his tongue, but it does put pressure on the corners of his mouth. The snaffle bit is correctly defined as a bit that promotes “direct rein action,” meaning that when you pull right, you go right and when you pull left, you go left. A snaffle bit does not have a shank. If it did have a shank, it would be considered a curb bit, regardless of how short the shank really is (as is the case with a Tom Thumb bit). Learning to go forward in the beginning of your equine’s training in a snaffle bridle is paramount to properly developing his body so he will learn to carry a rider in a strong and solid frame and in good equine posture. The forward training teaches him to stretch his head and neck forward, to step well underneath his body to propel himself forward, and to elongate his overall frame to keep the vertebrae in his back from becoming compressed and rigid. When he is moving correctly in a straight line, he will have more suspension and flexibility to his gait, and when he turns he will be able to bend easily through his rib cage.

Learning to go forward in the beginning of your equine’s training in a snaffle bridle is paramount to properly developing his body so he will learn to carry a rider in a strong and solid frame and in good equine posture. The forward training teaches him to stretch his head and neck forward, to step well underneath his body to propel himself forward, and to elongate his overall frame to keep the vertebrae in his back from becoming compressed and rigid. When he is moving correctly in a straight line, he will have more suspension and flexibility to his gait, and when he turns he will be able to bend easily through his rib cage. Although it would seem that a bitless bridle could achieve this same end, it has a different action on your equine’s head and neck, which inhibits proper bending through turns. The straight forward motion can be achieved with a bitless bridle. However, reins on a bosal (a type of braided rawhide noseband used with the hackamore-type headstall), bitless bridle reins, and other bitless configurations do not have the same lateral effect on the equine’s head and neck as does the snaffle bit. The equine’s head and neck form two sides of a triangle. The rope reins on a bosal, although lower on the nose of the equine than reins that come from the corners of the mouth, can cause the equine’s head to twist slightly sideways during the turn because, during any directional indication, the rawhide bosal around the nose twists through the rope reins which are both secured together underneath the jaw. The rope reins pull the underside of the bosal in the direction of the turn, but the nosepiece goes the opposite way and can cause your equine to improperly tilt his head through the turns. On bitless bridles, the reins are attached substantially higher than the corners of the equine’s mouth. When you pull on the reins attached higher on the equine’s jaw than where the bit would be as is the case with a halter or bitless bridle, the angle of pull is sharper and more abrupt, since the head side of the “triangle” is so much shorter than the length of the neck. It will cause the equine to try to turn his head too sharply from the poll, which can cause kinks and pain in his neck.

Although it would seem that a bitless bridle could achieve this same end, it has a different action on your equine’s head and neck, which inhibits proper bending through turns. The straight forward motion can be achieved with a bitless bridle. However, reins on a bosal (a type of braided rawhide noseband used with the hackamore-type headstall), bitless bridle reins, and other bitless configurations do not have the same lateral effect on the equine’s head and neck as does the snaffle bit. The equine’s head and neck form two sides of a triangle. The rope reins on a bosal, although lower on the nose of the equine than reins that come from the corners of the mouth, can cause the equine’s head to twist slightly sideways during the turn because, during any directional indication, the rawhide bosal around the nose twists through the rope reins which are both secured together underneath the jaw. The rope reins pull the underside of the bosal in the direction of the turn, but the nosepiece goes the opposite way and can cause your equine to improperly tilt his head through the turns. On bitless bridles, the reins are attached substantially higher than the corners of the equine’s mouth. When you pull on the reins attached higher on the equine’s jaw than where the bit would be as is the case with a halter or bitless bridle, the angle of pull is sharper and more abrupt, since the head side of the “triangle” is so much shorter than the length of the neck. It will cause the equine to try to turn his head too sharply from the poll, which can cause kinks and pain in his neck. To prove the point, try this experiment. Preferably using an untrained animal, take hold of the halter and gently but firmly pull on the halter in an attempt to make him bend his head and neck to the side. The higher position of the halter is like a bitless bridle and you will feel slight tension and resistance to this action before the animal finally complies. Next, gently insert two fingers into one corner of the equine’s mouth while standing at his shoulder and by squeezing and releasing your fingers, ask him to turn his head and neck to the side toward you. If done correctly, without yanking on him, he should give easily to your cue to submit and turn his head and neck. You will notice that he extends his head and neck slightly forward before turning it to the side.

To prove the point, try this experiment. Preferably using an untrained animal, take hold of the halter and gently but firmly pull on the halter in an attempt to make him bend his head and neck to the side. The higher position of the halter is like a bitless bridle and you will feel slight tension and resistance to this action before the animal finally complies. Next, gently insert two fingers into one corner of the equine’s mouth while standing at his shoulder and by squeezing and releasing your fingers, ask him to turn his head and neck to the side toward you. If done correctly, without yanking on him, he should give easily to your cue to submit and turn his head and neck. You will notice that he extends his head and neck slightly forward before turning it to the side. Now try this action on yourself. Stand in good posture and, without extending your neck, turn your head to the side. Do you feel the tension at the brainstem on the back of your neck? Now, stand in good posture, stretch your neck in an upward and forward arc and then look around the turn. Can you now feel the release from tension in the back of your neck? Your equine experiences the same feelings. The shorter angle of the side-pulls and bitless bridles will have a more abrupt pull and can cause some pain, while the longer angle coming from the snaffle bit at the corners of his mouth will allow a smoother and painless response. NOTE: Any bit can be painful to an animal when in the hands of an inexperienced rider who uses only the bit for control.

Now try this action on yourself. Stand in good posture and, without extending your neck, turn your head to the side. Do you feel the tension at the brainstem on the back of your neck? Now, stand in good posture, stretch your neck in an upward and forward arc and then look around the turn. Can you now feel the release from tension in the back of your neck? Your equine experiences the same feelings. The shorter angle of the side-pulls and bitless bridles will have a more abrupt pull and can cause some pain, while the longer angle coming from the snaffle bit at the corners of his mouth will allow a smoother and painless response. NOTE: Any bit can be painful to an animal when in the hands of an inexperienced rider who uses only the bit for control. The equine that has not had this kind of advanced training will possess neither genuinely good posture nor the knowledge of how to respond correctly in an abrupt and unpredictable situation. He will be more apt to be frightened and, as a result, may bolt and run, putting you and everyone around you at risk. However, the equine that is properly and conscientiously taught how to communicate through the snaffle bit will be a safer and more reliable animal to ride and to take into public places. He has learned to stop and wait for cues (communication through the bit) and is less likely to bolt and run if frightened because he understands and trusts the communication coming from his rider. He will now be more correct and solid in his good posture, yielding confidence in his attitude, and he will be a more reliable pleasure and show animal to ride.

The equine that has not had this kind of advanced training will possess neither genuinely good posture nor the knowledge of how to respond correctly in an abrupt and unpredictable situation. He will be more apt to be frightened and, as a result, may bolt and run, putting you and everyone around you at risk. However, the equine that is properly and conscientiously taught how to communicate through the snaffle bit will be a safer and more reliable animal to ride and to take into public places. He has learned to stop and wait for cues (communication through the bit) and is less likely to bolt and run if frightened because he understands and trusts the communication coming from his rider. He will now be more correct and solid in his good posture, yielding confidence in his attitude, and he will be a more reliable pleasure and show animal to ride.

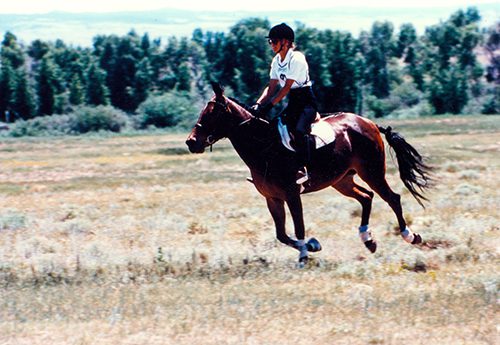

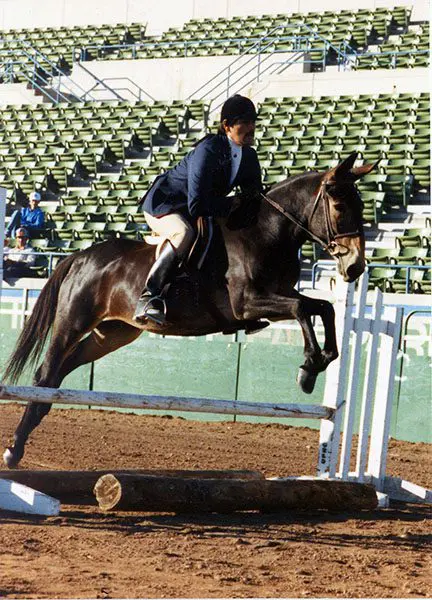

In 1986, when I first began using my mules in Dressage, you would never have convinced me that I would follow it up with jumping. I was fearful of jumping because of a few bad experiences I had with horses. However, once I took the time to learn to ride and train properly with Dressage and experienced the overall stability of a mule, my fear disappeared.

In 1986, when I first began using my mules in Dressage, you would never have convinced me that I would follow it up with jumping. I was fearful of jumping because of a few bad experiences I had with horses. However, once I took the time to learn to ride and train properly with Dressage and experienced the overall stability of a mule, my fear disappeared. If you speak to mule owners all over the world, you will hear at least one tale in ten about a mule jumping out of his pen. If they have the inclination, most mules have the ability to easily clear a fence up to and even over six feet high. The capability is certainly there, but in general, mules lack the motivation to expend the energy to actually jump out, especially when they are well managed.

If you speak to mule owners all over the world, you will hear at least one tale in ten about a mule jumping out of his pen. If they have the inclination, most mules have the ability to easily clear a fence up to and even over six feet high. The capability is certainly there, but in general, mules lack the motivation to expend the energy to actually jump out, especially when they are well managed. of a ballet dancer and that of a a weight lifter. A mule’s muscle structure (like that of a ballet dancer’s) is comprised of longer, smoother muscle with less bulky areas, a trait inherited from the donkey. This gives him a slightly more

of a ballet dancer and that of a a weight lifter. A mule’s muscle structure (like that of a ballet dancer’s) is comprised of longer, smoother muscle with less bulky areas, a trait inherited from the donkey. This gives him a slightly more  streamlined appearance than that of a horse. And like a ballet dancer, a mule can spring his body effortlessly into the air using the muscles in his hindquarters, giving him the ability to jump either from a standstill or while in motion. For the weight lifter or the horse, this maneuver is not as easy due to their particular muscle structure. So when selecting a horse for advanced jumping, it is wise to select a breed or type of horse that has less bulk muscle and more smooth muscle, like the mule., and both need the thickness o bone to absorb the concussion on the landings.

streamlined appearance than that of a horse. And like a ballet dancer, a mule can spring his body effortlessly into the air using the muscles in his hindquarters, giving him the ability to jump either from a standstill or while in motion. For the weight lifter or the horse, this maneuver is not as easy due to their particular muscle structure. So when selecting a horse for advanced jumping, it is wise to select a breed or type of horse that has less bulk muscle and more smooth muscle, like the mule., and both need the thickness o bone to absorb the concussion on the landings. Regardless of the mule’s inherent strength and endurance, in the beginning of jumping training, he will lack the muscle development and stamina required to negotiate a course of jumps effortlessly and in stride. Like any other living creature, he can only strengthen the muscles that he uses, so it is up to you to make sure he is doing specific exercises that pinpoint the correct sets of muscles so he can do his job over the jumps, between the jumps, before and after the jumps.

Regardless of the mule’s inherent strength and endurance, in the beginning of jumping training, he will lack the muscle development and stamina required to negotiate a course of jumps effortlessly and in stride. Like any other living creature, he can only strengthen the muscles that he uses, so it is up to you to make sure he is doing specific exercises that pinpoint the correct sets of muscles so he can do his job over the jumps, between the jumps, before and after the jumps. These three tasks require different postures that need to be supported by different muscle groups, so work on training and strengthening the specific exercises as outlined in DVD #7 of my Training Mules and Donkeys series. A proper conditioning program of exercises for your mule ro donkey will strengthen the muscles needed for jumping and will prepare him for a more polished performance. This is also a good opportunity to fine-tune all the muscles in your own body as you fine-tune those of your mule or any other equine.

These three tasks require different postures that need to be supported by different muscle groups, so work on training and strengthening the specific exercises as outlined in DVD #7 of my Training Mules and Donkeys series. A proper conditioning program of exercises for your mule ro donkey will strengthen the muscles needed for jumping and will prepare him for a more polished performance. This is also a good opportunity to fine-tune all the muscles in your own body as you fine-tune those of your mule or any other equine. While training your equine to jump, you must ask yourself some very important questions. Does my animal possess the strength of body to carry him from the hindquarters with sufficient impulsion, rhythm and balance? Can he readily lengthen or shorten his stride to accommodate the distance to his fences? Are these adjustments easily made, or does my equine tend to throw his weight onto his forehand during transitions between gaits and over fences? Remember, the animal that is well schooled in jumping will carry his body with ease and make smooth transitions from an uphill balance.

While training your equine to jump, you must ask yourself some very important questions. Does my animal possess the strength of body to carry him from the hindquarters with sufficient impulsion, rhythm and balance? Can he readily lengthen or shorten his stride to accommodate the distance to his fences? Are these adjustments easily made, or does my equine tend to throw his weight onto his forehand during transitions between gaits and over fences? Remember, the animal that is well schooled in jumping will carry his body with ease and make smooth transitions from an uphill balance. There are a series of exercises that will help to build your prospect into a beautiful, stylish and exciting jumper, but it will take time and patience— there just aren’t any shortcuts. Taking the time and exercising your patience will produce not only an animal that jumps properly, but one that is also strong and confident in his abilities. This can come in mighty handy later on when you find yourself in more demanding jumping situations. Having taught your equine to jump safely, you will have a more pleasurable and stress-free ride.

There are a series of exercises that will help to build your prospect into a beautiful, stylish and exciting jumper, but it will take time and patience— there just aren’t any shortcuts. Taking the time and exercising your patience will produce not only an animal that jumps properly, but one that is also strong and confident in his abilities. This can come in mighty handy later on when you find yourself in more demanding jumping situations. Having taught your equine to jump safely, you will have a more pleasurable and stress-free ride. more sure and stable. To me, a mule seems more balanced and stronger throughout than does a horse, and so the chance of taking a misstep or crashing a jump is lessened. Should a loss of balance or error occur, the mule is usually able to more quickly recover than the horse, making for a safer ride.

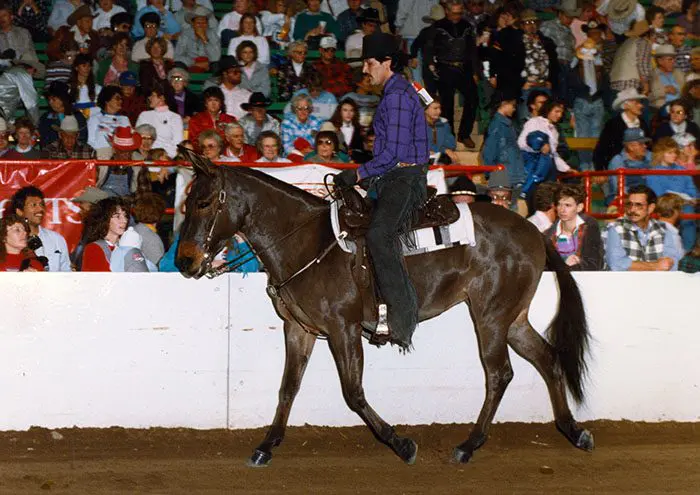

more sure and stable. To me, a mule seems more balanced and stronger throughout than does a horse, and so the chance of taking a misstep or crashing a jump is lessened. Should a loss of balance or error occur, the mule is usually able to more quickly recover than the horse, making for a safer ride. Today, mules are jumped in all kinds of events, from Combined Training to Hunter/Jumper classes. Jumping mules adds excitement and variety to training events and events where mules jump in competition under saddle against each other, and even against horses. Coon hunters often display the mule’s natural ability to jump from a standstill by jumping them in-hand over fences, either on hunts or at shows, and some mule owners even try their luck at Fox Hunting.

Today, mules are jumped in all kinds of events, from Combined Training to Hunter/Jumper classes. Jumping mules adds excitement and variety to training events and events where mules jump in competition under saddle against each other, and even against horses. Coon hunters often display the mule’s natural ability to jump from a standstill by jumping them in-hand over fences, either on hunts or at shows, and some mule owners even try their luck at Fox Hunting. other side of the fence and ask the mule to jump it. When this is a class at a show, it is staged very much the same way, but you will see more larger mules on display. By any standards, the mule’s capacity to jump is unquestionable, and there is no doubt he will continue to climb the ladder of equine success. The mule will often exceed people’s expectations, but in most cases he will out-perform his horse counterparts. Hambone proved this to be true when he jumped so well, won against the competition and got mules banned from competing against the horses again!

other side of the fence and ask the mule to jump it. When this is a class at a show, it is staged very much the same way, but you will see more larger mules on display. By any standards, the mule’s capacity to jump is unquestionable, and there is no doubt he will continue to climb the ladder of equine success. The mule will often exceed people’s expectations, but in most cases he will out-perform his horse counterparts. Hambone proved this to be true when he jumped so well, won against the competition and got mules banned from competing against the horses again!

Instead of going on the road to do clinics, I thought long and hard and decided to do an equestrian correspondence training course instead. I opted for this after considering that when I went to clinics as a student, I was one of 20 people and only got limited attention during those clinics. When I put into practice at home what I had learned at the clinics, I realized that I had only received the highlights of training and it was full of holes! When I tried to contact the clinicians to ask a question, I was either answered by someone in the office, or not answered at all. The clinicians were most often too busy and out of touch. The one thing I didn’t realize by making this decision was the incredible learning opportunity I had opened up for myself that I could, in turn, pass on to my clients.

Instead of going on the road to do clinics, I thought long and hard and decided to do an equestrian correspondence training course instead. I opted for this after considering that when I went to clinics as a student, I was one of 20 people and only got limited attention during those clinics. When I put into practice at home what I had learned at the clinics, I realized that I had only received the highlights of training and it was full of holes! When I tried to contact the clinicians to ask a question, I was either answered by someone in the office, or not answered at all. The clinicians were most often too busy and out of touch. The one thing I didn’t realize by making this decision was the incredible learning opportunity I had opened up for myself that I could, in turn, pass on to my clients. When they told me mules would not work well in a snaffle bit, I learned how to make that work. When they said they were not suitable for Dressage, I based my entire training program on those principles. When they told me not to give food rewards, I paid my mules for their efforts with a generous reward of crimped oats. When they told me not to talk to my equines, I spoke three languages to them: verbal language, body language and “touch” language. I can truthfully say that today I realize that it wasn’t the mules that were so stubborn, but rather…it was me! This positive kind of stubbornness did pay off, as I was to soon discover.

When they told me mules would not work well in a snaffle bit, I learned how to make that work. When they said they were not suitable for Dressage, I based my entire training program on those principles. When they told me not to give food rewards, I paid my mules for their efforts with a generous reward of crimped oats. When they told me not to talk to my equines, I spoke three languages to them: verbal language, body language and “touch” language. I can truthfully say that today I realize that it wasn’t the mules that were so stubborn, but rather…it was me! This positive kind of stubbornness did pay off, as I was to soon discover. Little Jack Horner had gone through my entire training series right along with my mules and had learned everything that I taught them. He may not have made it to Fourth Level Dressage, but he made it to Second Level Dressage with gait lengthening and lateral work. He overcame his “donkey” behaviors and gave a phenomenal performance, jumping four feet in exhibition at Bishop Mule Days. His Reining was accurate though somewhat limited by his donkey conformation. Still, he could always elicit a supportive laugh and a wide grin! He competed successfully at dressage driving shows and won world championships in driving at Bishop Mule Days.

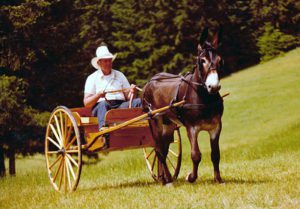

Little Jack Horner had gone through my entire training series right along with my mules and had learned everything that I taught them. He may not have made it to Fourth Level Dressage, but he made it to Second Level Dressage with gait lengthening and lateral work. He overcame his “donkey” behaviors and gave a phenomenal performance, jumping four feet in exhibition at Bishop Mule Days. His Reining was accurate though somewhat limited by his donkey conformation. Still, he could always elicit a supportive laugh and a wide grin! He competed successfully at dressage driving shows and won world championships in driving at Bishop Mule Days. It was during this experience that I realized that Little Jack Horner had become deaf and could not hear one word of what I was saying, even when I was yelling. I was sitting in the Meadowbrook cart, he had blinders on his harness bridle and could not see me, so verbal language and body language were of no help to him at all. Lucky for us, we still had the “touch” language that we had developed between us and we thoroughly enjoyed the experience of driving yet again.

It was during this experience that I realized that Little Jack Horner had become deaf and could not hear one word of what I was saying, even when I was yelling. I was sitting in the Meadowbrook cart, he had blinders on his harness bridle and could not see me, so verbal language and body language were of no help to him at all. Lucky for us, we still had the “touch” language that we had developed between us and we thoroughly enjoyed the experience of driving yet again.