MULE CROSSING: What are Mules Good for Besides Packing and Farming?

By Meredith Hodges

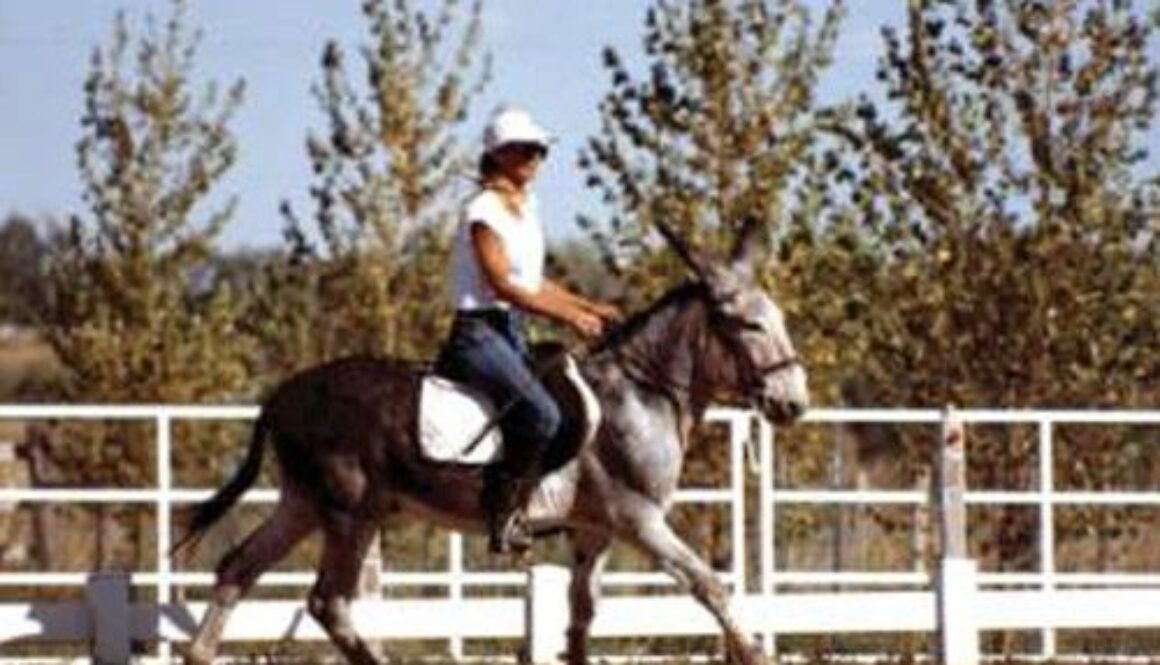

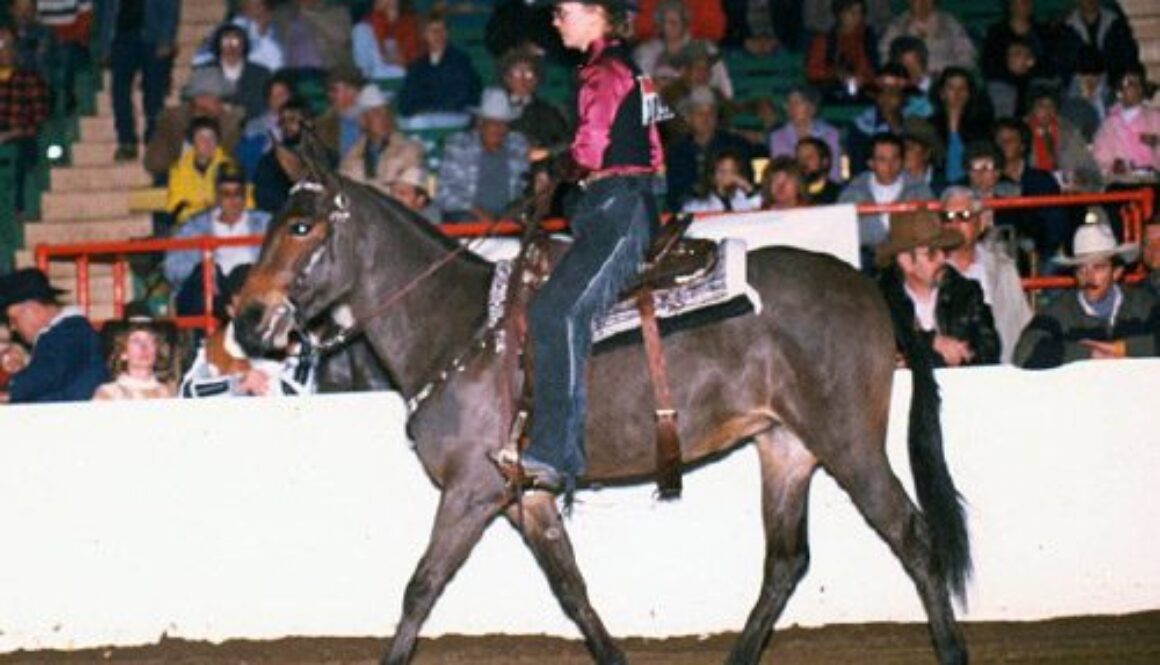

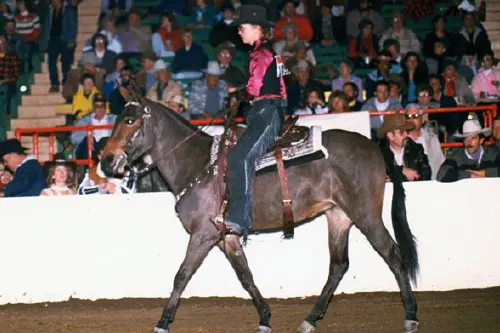

The modern contemporary mule of the late 1970s has emerged as a fine saddle, driving and pack animal. No longer does he come from exclusively low grade mares. With the upgrading of mule breeding, the mule is a new, gentle and versatile animal capable of performing well in all forms of equine athletics. He can do cow work, work and pleasure driving, packing, jumping and is better suited for long trails, yet he still possesses all the traits that have made mules popular throughout the centuries: a willingness to work, an easy keeper, more resistance to parasites and disease, extremely surefooted and his indubitable intelligence that is often confused with stubbornness.

The modern contemporary mule of the late 1970s has emerged as a fine saddle, driving and pack animal. No longer does he come from exclusively low grade mares. With the upgrading of mule breeding, the mule is a new, gentle and versatile animal capable of performing well in all forms of equine athletics. He can do cow work, work and pleasure driving, packing, jumping and is better suited for long trails, yet he still possesses all the traits that have made mules popular throughout the centuries: a willingness to work, an easy keeper, more resistance to parasites and disease, extremely surefooted and his indubitable intelligence that is often confused with stubbornness.

Mules are capable of being used for as many different things as are all breeds of horses put together. Since a mule gets most of his ability from the mare, one need only scout a mule out of a  particular kind of horse to match the desired ability. A mule out of any breed of horse will be stronger and more durable than the horse out of which he came.

particular kind of horse to match the desired ability. A mule out of any breed of horse will be stronger and more durable than the horse out of which he came.

Mules played an important role in our country during the Reconstruction Period: they patiently worked the fields, packed necessary artillery for the army, and served as a durable riding and driving animal in the westward movement.

With the coming of the industrial age, their uses were minimized and they were faced with the possibility of extinction in the march of progress. Today, through the persistent determination of mule enthusiasts, mules are once again emerging as a conceivable asset to our economy and a unique form of athletic achievement and entertainment.

With the coming of the industrial age, their uses were minimized and they were faced with the possibility of extinction in the march of progress. Today, through the persistent determination of mule enthusiasts, mules are once again emerging as a conceivable asset to our economy and a unique form of athletic achievement and entertainment.

With new and improved training techniques, the mules of today are known for their beauty and outstanding athletic ability, their durability and their intelligence. Their uses are limited only to the imaginations of their owners. It is now commonly known that with proper training, a mule can perform better than the horse it was bred from. Subsequently, mules are not only competing in mule shows, but horse shows as well—in events from cutting to dressage. Cattle ranchers have discovered the mule to be an important asset in their business. He can go all day without tiring and can cover terrain that might discourage a horse, not to mention that the ride is much more comfortable.

Hunters caught in the heavy snows of the Rocky Mountains praise their mules for carrying out heavy game and blazing trails through treacherous snowy ground, leading them and their horses to safety. Sales persons are grateful to both mules and donkeys for their humorous contributions in advertising and children appreciate the companionship and affection that mules can offer.

Even the army has conceded that mules could make their contribution to the economy through their use in mountain light infantry divisions. The only problem that arises is educating people on mule psychology so that they can train them properly.

Even the army has conceded that mules could make their contribution to the economy through their use in mountain light infantry divisions. The only problem that arises is educating people on mule psychology so that they can train them properly.

Though we are still a busy society, with the help of technology we are more able to give the mule the time and appreciation he deserves. Consequently, we are continually discovering new uses for the much-maligned mule, enjoying him more, and in the process, we’re putting the old wives’ tales to rest.

Yesterday’s mules sturdy and strong

Yesterday’s mules sturdy and strong

The days in the fields were often quite long

The man with the whip sometimes evened the score

With a jolt to the head by a stout two-by-four.

“Understanding” a word not common for slaves

Caused many good mules to go to their graves

“Stubborn and cranky are mules,” said most men

Who used and abused them then were kicked or bitten.

When industry triumphed, the mules quickly faded

But the tales remained and were often quite jaded

Twas never the man with the stout two-by-four

Who was wrong from the start to push mules way too far

But the folks who were ignorant knew only what’s said

And since mules cannot talk, their reputation was dead

They’re known to be pushy, vengeful, and cross

So man abandoned the mule for his exquisite horse.

But even after the industrial revolution, mules exhibited their versatility and once again defined their use for the new age. The military dispersed their cavalries and sold most of their mules in lieu of motorized all-terrain vehicles. However, when they got up into the Rocky Mountains, they still found some areas impenetrable and had to resort to the use of pack mules yet again. In California, there is still a Military Mountain Mule Training Camp. And just recently…

INTERNET

Mules are being used to carry supplies into Western North Carolina

The animals are being used to carry water, diapers and other much-needed essentials into communities isolated after Helene.

Author: James Brierton (WCNC)

Published: 3:29 PM EDT October 1, 2024

Updated: 3:29 PM EDT October 1, 2024

Facebook

WEAVERVILLE, N.C. — After Helene isolated western North Carolina communities with landslides, flash flooding and road damage good Samaritans have had to find creative ways to bring in much-needed supplies.

WEAVERVILLE, N.C. — After Helene isolated western North Carolina communities with landslides, flash flooding and road damage good Samaritans have had to find creative ways to bring in much-needed supplies.

In addition to aircraft drops by military and civilian pilots, mule packers are using the animals to walk supplies into mountainous communities.

“Mules and equipment are loaded, and the first big batch of supplies has been purchased and loaded,” the Mountain Mule Packer Ranch posted on Facebook Monday. “We have two fully loaded trucks and 20′ stock trailers heading to WNC for assistance!”

Later Monday, the ranchers posted pictures of the animals and supply cargo to social media.

“We will be setting up a staging area and beginning to assist this afternoon,” they wrote on Monday, “and will be bringing up additional loads of supplies once mules are in place!”

“We will be setting up a staging area and beginning to assist this afternoon,” they wrote on Monday, “and will be bringing up additional loads of supplies once mules are in place!”

Mountain Mule Packer Ranch is based out of Mount Ulla, which is located between Lake Norman and Salisbury in North Carolina. They have been using their Facebook page to announce when they will be at the Food Lion, located at 11745 Statesville Blvd. in Cleveland, NC, to collect donations.

Mountain Mule Packer Ranch is based out of Mount Ulla, which is located between Lake Norman and Salisbury in North Carolina. They have been using their Facebook page to announce when they will be at the Food Lion, located at 11745 Statesville Blvd. in Cleveland, NC, to collect donations.

Busy morning as we loaded lots of equipment, supplies, and MULES, to leave for WNC! Please know that we appreciate EVERY kind word, gesture of support, and all that are partnering with us to HELP all that we can! We will be setting up a staging area and beginning to assist this afternoon and will be bringing up additional loads of supplies once mules are in place! #prayingforthoseaffectedbyhelene #mulepower #StrongerTogether #mountainmulepackers #militarymules

The Mountain Mule Packer Ranch partnered with the Cajun Navy, another group of civilian volunteers, to deliver insulin to a family on Monday, according to their Facebook posts.

The Mountain Mule Packer Ranch partnered with the Cajun Navy, another group of civilian volunteers, to deliver insulin to a family on Monday, according to their Facebook posts.

The ranchers have setup their staging area in Montreat on Tuesday. They were planning to make trips into Black Mountain.

Mountain Mule Packer Ranch

October 1, 6:31 a.m.

8:30am update 10/1/24 Mike and the mule team made it to their staging area in Montreat yesterday and have already been helpful to families in need! They will be doing all they can in Black Mountain today. Thankful to Five 11’s Livestock Hauling for offering help in hauling mules so we could bring more supplies up! And appreciate being able to help support Cajun Navy 2016 on their efforts as well!

8:30am update 10/1/24 Mike and the mule team made it to their staging area in Montreat yesterday and have already been helpful to families in need! They will be doing all they can in Black Mountain today. Thankful to Five 11’s Livestock Hauling for offering help in hauling mules so we could bring more supplies up! And appreciate being able to help support Cajun Navy 2016 on their efforts as well!

The team here at the ranch will be shopping for more supplies today, to restock them tomorrow! We appreciate the huge outpouring of requests on how to get supplies to us. Because of the conditions in the mountains and the way the team will be moving around, that is hard to coordinate. I will bring a trailer to the Food Lion Shopping Center this afternoon at approximately 4pm if there is anyone in the area that wants to add to the supplies we are bringing! Please let me know if this is something you’d like to do, and we can be there between 4-5pm today to collect what you have!! God bless you all, and thank you for keeping prayers lifted up!!

The team here at the ranch will be shopping for more supplies today, to restock them tomorrow! We appreciate the huge outpouring of requests on how to get supplies to us. Because of the conditions in the mountains and the way the team will be moving around, that is hard to coordinate. I will bring a trailer to the Food Lion Shopping Center this afternoon at approximately 4pm if there is anyone in the area that wants to add to the supplies we are bringing! Please let me know if this is something you’d like to do, and we can be there between 4-5pm today to collect what you have!! God bless you all, and thank you for keeping prayers lifted up!!

Food Lion 11745 Statesville Blvd., Cleveland, NC

EQUUS MAGAZINE

Horse, mule groups aid NC storm victims

Much-needed supplies are being packed and airlifted into affected areas

October 3, 2024

⎯ Edited Press Release

NOTE: This is a developing story that will be updated periodically.

A force of nature called Helene made landfall as a deadly category 4 hurricane late on the evening of September 26, 2024, along the Florida Gulf Coast. One day later, as Helene weakened to a tropical storm, it unleashed damaging winds, unprecedented rainfall and torrential flooding across the southeast U.S., with Georgia and the Carolinas particularly hard hit. Donated hay/Sandhills Pony Club social media.

In some cases, entire inland communities have been wiped out in scenes described as “apocalyptic.” The degree of destruction is staggering, and the death toll continues to rise, with rescue operations in full swing and hundreds of people still believed missing at this writing. In the wake of the devastation, groups such as the Mountain Mule Packer Ranch in Mount Ulla, North Carolina, and the Sandhills Pony Club of Pinebluff, North Carolina, have mobilized to help victims of Helene in that state’s western mountains, many of whom have been stranded for days without food, water, cell power, electricity and passable roads.

Their targets include not only the people in these locations, but their animals, as well.

Packing it in

In the case of the Mountain Mule Packer Ranch, a business that offers training in tactical mule packing, the objective is getting much-needed supplies in by pack mule strings to especially hard-to-reach mountain locations. The mules and supplies are being hauled to local staging areas from which they are being deployed. According to reports, each of the mules can carry 200 pounds of supplies, everything from food and water to diapers and medical needs like insulin.

In a recent Facebook post, the Mountain Mule Packer Ranch asked that anyone who wants to donate to their mission or who knows of “specific needs and areas” where mule-string help might be warranted please reach out to them at (910) 885-1402. “We can bring supplies or pack in what your group has acquired already,” the post reads. There have also been reports of vital supplies being carried into the mountains by individuals on horseback.

Airlifting hay and animal feed

Meanwhile, members of the Sandhills Pony Club are using airlifts and ATVs to transport donated hay, feed and animal supplies into zones where horses, other livestock and pets have not been evacuated.

Recently added to the pony club’s wish list: Pet food in easily transportable sizes, roll-type temporary fencing, five-gallon jugs for water and small bags of high-performance dog food like Purina Pro-Plan and Diamond Performance (no chicken, please) for the hardworking Search and Rescue dogs.

The group is also asking for additional volunteers to help coordinate this massive relief effort. Call (615) 268-9145 or email sandhillsponyclub@gmail.com for more information.

A post on the club’s Facebook page directs those wishing to help to send donations by Venmo (@Sandhills_PonyClub) or mail a check to Sandhills Pony Club, 255 Cliffman Rd., Pinebluff, NC 28373.

Landing page image from Mountain Mule Packer Ranch social media

“With more time to our leisure the mules of today

Are treated much better and perform just that way

The love and affection the mules can now give

Makes raising and training a warm way to live.

To meet them and greet them, to own one or not

The mules of today exhibit just what they got!

We’ve banned the “Old Wives’ Tales” and made a new rule

If you aren’t too stubborn, why not ride a mule!”

Again with the devastation in North Carolina, South Caroline, Georgia, Florida, Alabama and Tennessee, mules are once again traveling far into areas that prohibit motorized vehicles from going. There are particularly remote areas in the Appalachian Mountains that can be truly difficult to navigate due to extremely steep trail and low hollers along the riverbanks as described in a book I read about the first women on mules that delivered books to these remote areas. Private citizens with their mules and horses were timely in their response and are definitely continuing to make a difference in the lives of the people who have been left homeless and floundering after this horrible disaster. Mules will always be an asset to our American way of life due to their outstanding characteristics, versatility and ability to go where not all men can go!

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com, MEREDITH HODGES PUBLIC FIGURE Facebook page, or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Pinterest, Instagram, MeWe, YouTube and Twitter.

Covered in TRAINING MULES & DONKEY: A LOGICAL APPROACH TO TRAINING, TRAINING WITHOUT RESISTANCE and EQUUS REVISITED at www.luckythreeranchstore.com.

© 1985, 2016, 2024 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

It is important to know the differences among rewards, treats, coaxing and bribing in order to correctly employ the reward system of training called Behavior Modification.

It is important to know the differences among rewards, treats, coaxing and bribing in order to correctly employ the reward system of training called Behavior Modification. Remember to give your equine a reward only after a specific task you’ve asked for has been performed—or even an assimilation of that task, which means the taking of baby steps toward completing the task. The reward should be given immediately upon completion of the task and then your equine should be allowed time to enjoy his reward before moving on to the next task. If your equine is given a food reward for only good behaviors, he will be more likely to continue to repeat only those behaviors for which he is rewarded and you can begin to “shape” his behavior in a positive way.

Remember to give your equine a reward only after a specific task you’ve asked for has been performed—or even an assimilation of that task, which means the taking of baby steps toward completing the task. The reward should be given immediately upon completion of the task and then your equine should be allowed time to enjoy his reward before moving on to the next task. If your equine is given a food reward for only good behaviors, he will be more likely to continue to repeat only those behaviors for which he is rewarded and you can begin to “shape” his behavior in a positive way. As an example of coaxing, you can extend a handful of crimped oats to lure your equine closer to an obstacle, but he should not receive the handful of oats until he completes the required task or travels enough distance toward the obstacle to deserve a reward. If your equine just won’t come all the way to an obstacle, even to get a reward, you can modify the task by asking your equine to just come closer to the obstacle and then halt (but without backing up). Then the reward can be dispensed for the partial approach and halt, because these actions still qualify as an assimilation of the bigger task that is to be completed. If he backs away at all, he should not be rewarded and you will have to go back to the beginning of the task and try again.

As an example of coaxing, you can extend a handful of crimped oats to lure your equine closer to an obstacle, but he should not receive the handful of oats until he completes the required task or travels enough distance toward the obstacle to deserve a reward. If your equine just won’t come all the way to an obstacle, even to get a reward, you can modify the task by asking your equine to just come closer to the obstacle and then halt (but without backing up). Then the reward can be dispensed for the partial approach and halt, because these actions still qualify as an assimilation of the bigger task that is to be completed. If he backs away at all, he should not be rewarded and you will have to go back to the beginning of the task and try again. Between lessons, let your equine have a day off in order to rest. When you return for the second lesson, tie him to the fence and review with him your last lesson from the very beginning. He should remember the previous lessons and be willing to follow you right away in order to be rewarded. If he seems willing to follow your lead, untie him and ask him to take a step forward just as he did before, but this time, instead of dispensing the food reward when he takes the first step forward, simply say, “Good boy” and ask him for a second step forward before you reward him with the oats. You will now be progressing from one step forward before you reward to two steps forward before you reward.

Between lessons, let your equine have a day off in order to rest. When you return for the second lesson, tie him to the fence and review with him your last lesson from the very beginning. He should remember the previous lessons and be willing to follow you right away in order to be rewarded. If he seems willing to follow your lead, untie him and ask him to take a step forward just as he did before, but this time, instead of dispensing the food reward when he takes the first step forward, simply say, “Good boy” and ask him for a second step forward before you reward him with the oats. You will now be progressing from one step forward before you reward to two steps forward before you reward. This is how you begin with leading training, and also how you should proceed with all the new things that you will be teaching your equine. In the beginning of leading training, he gets rewarded for even an assimilation of what you’re asking. For example, when you get to negotiating obstacles, your goal may be to cross over a bridge, but when your equine sees the bridge ahead, he may stop or start backing up. At this point, allow him to back until he stops. Go back and repeat the steps you did prior to approaching the obstacle. Then, asking for only one step at a time, proceed as you did during his flatwork leading training toward the bridge, rewarding each step he takes. Tell him verbally how brave he is and continue to reward any steps he takes toward the obstacle before proceeding forward. Remember to stop at any interval where he becomes tense, ask for one more step to be rewarded, and then allow him to settle and refocus before asking any more from him.

This is how you begin with leading training, and also how you should proceed with all the new things that you will be teaching your equine. In the beginning of leading training, he gets rewarded for even an assimilation of what you’re asking. For example, when you get to negotiating obstacles, your goal may be to cross over a bridge, but when your equine sees the bridge ahead, he may stop or start backing up. At this point, allow him to back until he stops. Go back and repeat the steps you did prior to approaching the obstacle. Then, asking for only one step at a time, proceed as you did during his flatwork leading training toward the bridge, rewarding each step he takes. Tell him verbally how brave he is and continue to reward any steps he takes toward the obstacle before proceeding forward. Remember to stop at any interval where he becomes tense, ask for one more step to be rewarded, and then allow him to settle and refocus before asking any more from him. Now you no longer need to reward for one foot on the bridge. This is called “fading or phasing out” the reward for a previous behavior (one step), while introducing the new behavior of walking to the bridge, halting and then putting two front feet up on the bridge. Wait for a moment for him to chew his reward and then ask him to continue onto the bridge, stop and square up with four feet on the bridge and reward. If he does not comply and won’t stop on the bridge, just go back to the beginning, approach the bridge as described and try again until he stops to be rewarded with all four feet placed squarely on the bridge

Now you no longer need to reward for one foot on the bridge. This is called “fading or phasing out” the reward for a previous behavior (one step), while introducing the new behavior of walking to the bridge, halting and then putting two front feet up on the bridge. Wait for a moment for him to chew his reward and then ask him to continue onto the bridge, stop and square up with four feet on the bridge and reward. If he does not comply and won’t stop on the bridge, just go back to the beginning, approach the bridge as described and try again until he stops to be rewarded with all four feet placed squarely on the bridge The last step over the bridge is to bring the hind feet off the bridge, stop and square up one more time before he gets rewarded. This does two things. It causes your equine to be attentive to the number of steps you are asking and it puts him in good posture at each stage so that his body will develop properly. In future lessons, the steps in the approach to the bridge no longer need to be rewarded and as he becomes more attentive, he will learn to stop any time you ask and wait for your cue to proceed. After several months of this meticulous attention to these detailed steps, he will not necessarily need to be rewarded with the food reward each time—a pat on the neck and kind words of support should be sufficient. Rewards can then be given for whole “blocks” of steps when he successfully completes them.

The last step over the bridge is to bring the hind feet off the bridge, stop and square up one more time before he gets rewarded. This does two things. It causes your equine to be attentive to the number of steps you are asking and it puts him in good posture at each stage so that his body will develop properly. In future lessons, the steps in the approach to the bridge no longer need to be rewarded and as he becomes more attentive, he will learn to stop any time you ask and wait for your cue to proceed. After several months of this meticulous attention to these detailed steps, he will not necessarily need to be rewarded with the food reward each time—a pat on the neck and kind words of support should be sufficient. Rewards can then be given for whole “blocks” of steps when he successfully completes them. In the natural progression of correct training—including during mounting training—your equine should also be getting rewarded when you’re first getting him used to your being on-board. Give him the oats reward for standing still while you attempt to mount (i.e., walking toward him, holding the left rein and reaching for the saddle horn), and then when you hang from each side of his body with a foot in the stirrup (first on one side and then on the other side), and, finally, from each side of his body while you sit on his back. When you ask him to turn his head to take the oats from your hand, you can be sure his attention will be on you because this action will force him to look at you in order to receive his oats. Then reward him again for standing still as you dismount. Consequently, by the time you actually get to the point of riding in an open arena, he’s been rewarded for having you on his back and for behaving well through all the exercises demanded from him during round pen training.

In the natural progression of correct training—including during mounting training—your equine should also be getting rewarded when you’re first getting him used to your being on-board. Give him the oats reward for standing still while you attempt to mount (i.e., walking toward him, holding the left rein and reaching for the saddle horn), and then when you hang from each side of his body with a foot in the stirrup (first on one side and then on the other side), and, finally, from each side of his body while you sit on his back. When you ask him to turn his head to take the oats from your hand, you can be sure his attention will be on you because this action will force him to look at you in order to receive his oats. Then reward him again for standing still as you dismount. Consequently, by the time you actually get to the point of riding in an open arena, he’s been rewarded for having you on his back and for behaving well through all the exercises demanded from him during round pen training.

The hinny is a somewhat slower and more meticulous mover than the mule, but a laid back mule can offer similar characteristics. The hinny inherits his way of going from the jennet as does the mule, which tends to be a little faster, more energetic and more agile—like his dam, the mare. The hinny, because of his meticulous way of going, is actually better in very steep, rocky terrain and, especially, in loose rock, and will not tire as quickly as a mule. Hinnies are the preferred equine in Mexico and Central America due to their diligence when working. Gaited hinnies are preferable in this kind of terrain where there is little opportunity to gallop because they have a smooth, more ground-covering gait and offer a smooth ride.

The hinny is a somewhat slower and more meticulous mover than the mule, but a laid back mule can offer similar characteristics. The hinny inherits his way of going from the jennet as does the mule, which tends to be a little faster, more energetic and more agile—like his dam, the mare. The hinny, because of his meticulous way of going, is actually better in very steep, rocky terrain and, especially, in loose rock, and will not tire as quickly as a mule. Hinnies are the preferred equine in Mexico and Central America due to their diligence when working. Gaited hinnies are preferable in this kind of terrain where there is little opportunity to gallop because they have a smooth, more ground-covering gait and offer a smooth ride. The hooves of a hinny tend to be more donkey-like—narrow, oval and more upright—where the hooves of a mule will look more horse-like; a little rounder (although still oval), with slightly more angle than the donkey hoof, but not as flat, round and angled as the horse’s hoof. On both hinnies and mules, the hooves should be trimmed more upright and the heels should be left longer than the hooves of the horse.

The hooves of a hinny tend to be more donkey-like—narrow, oval and more upright—where the hooves of a mule will look more horse-like; a little rounder (although still oval), with slightly more angle than the donkey hoof, but not as flat, round and angled as the horse’s hoof. On both hinnies and mules, the hooves should be trimmed more upright and the heels should be left longer than the hooves of the horse.

come in more colors than a horse, even an Appaloosa. Mule’s conformation falls somewhere in between that of the donkey and that of the horse. Mules inherit the best traits from both its sire and its dam. Mules get their athletic ability from the horse, while strength and intelligence come from the donkey. Mules today come in all shapes sizes and colors, from minis under 50 pounds to maxis over 1000 pounds, and in many different colors. Mules from Appaloosa mares produce wildly colored mules, much like their Appaloosa horse relatives, but with even wilder skewed colors. The Appaloosa color is produced by a complex of genes known as the Leopard Complex (Lp). Mares homozygous for the Lp gene bred to any color donkey will produce an Appaloosa colored mule.

come in more colors than a horse, even an Appaloosa. Mule’s conformation falls somewhere in between that of the donkey and that of the horse. Mules inherit the best traits from both its sire and its dam. Mules get their athletic ability from the horse, while strength and intelligence come from the donkey. Mules today come in all shapes sizes and colors, from minis under 50 pounds to maxis over 1000 pounds, and in many different colors. Mules from Appaloosa mares produce wildly colored mules, much like their Appaloosa horse relatives, but with even wilder skewed colors. The Appaloosa color is produced by a complex of genes known as the Leopard Complex (Lp). Mares homozygous for the Lp gene bred to any color donkey will produce an Appaloosa colored mule.

Zorse, Golden Zebra, Zebra mule, Zebrule: zebra father + horse mother

Zorse, Golden Zebra, Zebra mule, Zebrule: zebra father + horse mother

The embryo was from a Paso Fino Mare called La Querencia and the Paso Fino Donkey Cosaco XVI de Villa Luz. The pregnancy was 11 months and the delivery was normal with no complications, the mule knew exactly what to do and behaved as an expert mother even if it was her first time! The baby is a female and it was called “La bien querida” (The much loved).

The embryo was from a Paso Fino Mare called La Querencia and the Paso Fino Donkey Cosaco XVI de Villa Luz. The pregnancy was 11 months and the delivery was normal with no complications, the mule knew exactly what to do and behaved as an expert mother even if it was her first time! The baby is a female and it was called “La bien querida” (The much loved). Even if most mules are sterile, they have a maternal instinct, we had a case in our Farm where the mule La Rosa de Villa Luz, fell in love with a foal of a mare and tried to steal it, she kept very close to it for weeks, showing angry signs to the mare and a maternal attitude to the foal; when the mare and the foal were transferred to another pasture, the mule brayed for days. We have also been told of another case where an orphan foal was adopted by a mule and after two days the mule started producing milk!

Even if most mules are sterile, they have a maternal instinct, we had a case in our Farm where the mule La Rosa de Villa Luz, fell in love with a foal of a mare and tried to steal it, she kept very close to it for weeks, showing angry signs to the mare and a maternal attitude to the foal; when the mare and the foal were transferred to another pasture, the mule brayed for days. We have also been told of another case where an orphan foal was adopted by a mule and after two days the mule started producing milk! In Morocco, a mare mule produced a male foal that was 75 percent donkey and 25 percent horse (i.e., she passed on a mixture of genes instead of passing on her maternal chromosomes in the expected way). Miracle mule ‘confirmed’ DNA tests have confirmed that a Moroccan mule did give birth to a foal. Veterinary experts say the foal’s father was a donkey and its mother a true mule. “The foal inherited a mixture of horse and donkey chromosomes via the mother’s ovum ”

In Morocco, a mare mule produced a male foal that was 75 percent donkey and 25 percent horse (i.e., she passed on a mixture of genes instead of passing on her maternal chromosomes in the expected way). Miracle mule ‘confirmed’ DNA tests have confirmed that a Moroccan mule did give birth to a foal. Veterinary experts say the foal’s father was a donkey and its mother a true mule. “The foal inherited a mixture of horse and donkey chromosomes via the mother’s ovum ”

In 1995, a group from the Federal University of Minas Gerais described a female mule that was pregnant for a seventh time, having previously produced two donkey sires, two foals with the typical 63 chromosomes of mules, and several horse stallions that had produced four foals. The three of the latter available for testing each bore 64 horse-like chromosomes. These foals phenotypically resembled horses, though they bore markings absent from the sire’s known lineages, and one had ears noticeably longer than those typical of her sire’s breed. The elder two horse-like foals had proved fertile at the time of publication, with their progeny being typical of horses.

In 1995, a group from the Federal University of Minas Gerais described a female mule that was pregnant for a seventh time, having previously produced two donkey sires, two foals with the typical 63 chromosomes of mules, and several horse stallions that had produced four foals. The three of the latter available for testing each bore 64 horse-like chromosomes. These foals phenotypically resembled horses, though they bore markings absent from the sire’s known lineages, and one had ears noticeably longer than those typical of her sire’s breed. The elder two horse-like foals had proved fertile at the time of publication, with their progeny being typical of horses. Blood samples and other “technical testing” have verified that Blue Moon is indeed the first scientifically verified mule colt foaled from a molly mule. In mid-August, the Sylvesters received word from Dr. Benirschke with the big news: Krause is a true molly mule with 63 chromosomes and her new son Blue Moon is also a mule with 63 chromosomes. The father and grandfather is a verified jackass with 62 chromosomes, and the grandmother a true female horse with 64 chromosomes.

Blood samples and other “technical testing” have verified that Blue Moon is indeed the first scientifically verified mule colt foaled from a molly mule. In mid-August, the Sylvesters received word from Dr. Benirschke with the big news: Krause is a true molly mule with 63 chromosomes and her new son Blue Moon is also a mule with 63 chromosomes. The father and grandfather is a verified jackass with 62 chromosomes, and the grandmother a true female horse with 64 chromosomes. SPOKANE – Two weeks after announcing the birth of the first cloned mule, the same research team said a second cloned mule with identical DNA has been born. The mule, named Utah Pioneer, was born natural and unassisted Monday morning. The male foal joined his brother, Idaho Gem, whose birth was announced May 29, as the only equine clones in the world. The clones are the result of work by researchers Gordon Woods and Dirk Vanderwall from the

SPOKANE – Two weeks after announcing the birth of the first cloned mule, the same research team said a second cloned mule with identical DNA has been born. The mule, named Utah Pioneer, was born natural and unassisted Monday morning. The male foal joined his brother, Idaho Gem, whose birth was announced May 29, as the only equine clones in the world. The clones are the result of work by researchers Gordon Woods and Dirk Vanderwall from the

dominance in a non-threatening manner. This is accomplished through the use of a great deal of positive reinforcement early on, including gentle touches, a reassuring voice and lots of rewards for good behavior. Expressions of disapproval should be kept to a minimum and the negative reinforcement for bad behavior should be clear, concise and limited.

dominance in a non-threatening manner. This is accomplished through the use of a great deal of positive reinforcement early on, including gentle touches, a reassuring voice and lots of rewards for good behavior. Expressions of disapproval should be kept to a minimum and the negative reinforcement for bad behavior should be clear, concise and limited. mischievous? Has he been calm and accepting of most things until now? And, most important, is my own body language causing this to occur? Once I was willing to spend more time with regard to balance on the lead rope exercises and proceeded to the round pen to learn to balance on the circle, I soon discovered that developing good balance and posture was critical to a mule’s training. The reason my mule was pulling on the lunge line so hard was because he just could not balance his own body on a circle. Once I reviewed the leading exercises with him—keeping balance, posture and coordination in mind—and then went to the round pen to learn to balance on the circle, I noticed there was a lot less resistance to everything he was doing. I introduced the lunge line in the round pen and taught him how to circle with slack in the line. After that, lunging in the open arena on the lunge line was much easier and he did maintain the slack in the line while circling me.

mischievous? Has he been calm and accepting of most things until now? And, most important, is my own body language causing this to occur? Once I was willing to spend more time with regard to balance on the lead rope exercises and proceeded to the round pen to learn to balance on the circle, I soon discovered that developing good balance and posture was critical to a mule’s training. The reason my mule was pulling on the lunge line so hard was because he just could not balance his own body on a circle. Once I reviewed the leading exercises with him—keeping balance, posture and coordination in mind—and then went to the round pen to learn to balance on the circle, I noticed there was a lot less resistance to everything he was doing. I introduced the lunge line in the round pen and taught him how to circle with slack in the line. After that, lunging in the open arena on the lunge line was much easier and he did maintain the slack in the line while circling me. beginning to get your own body to assimilate correctness. In the beginning, a rider cannot “feel” the hind legs coming under his seat, so he needs to learn by watching the front legs moving forward along with his hands. With practice, the rider will develop the “feel” and will no longer need to watch the front legs moving forward. Remember, we all perceive things a little differently, and our perception depends on how we are introduced to something and on whether or not we can understand or perform a task.

beginning to get your own body to assimilate correctness. In the beginning, a rider cannot “feel” the hind legs coming under his seat, so he needs to learn by watching the front legs moving forward along with his hands. With practice, the rider will develop the “feel” and will no longer need to watch the front legs moving forward. Remember, we all perceive things a little differently, and our perception depends on how we are introduced to something and on whether or not we can understand or perform a task. Achieving balance and harmony with your mule requires more than just balancing and conditioning your mule’s body. As you begin to finish-train your mule, you should shift your awareness more toward your own body. Your mule should already be moving forward fairly steadily and in a longer frame, and basically be obedient to your aids. The objective of finish-training is to build the muscles in your own body, which will cause your aids to become more effective and clearly defined. This involves shedding old habits and building new ones, which takes a lot of time and should not be approached with any impatience. Remember: there are no shortcuts. In order to stabilize your hands and upper body, you need to establish a firm base in your seat and legs. Ideally, you should be able to drop a plumb line from your ear to your shoulder, down through your hips, through your heels and to the ground. To maintain this plumb line, work to make your joints and muscles in your body more supple and flexible by using them correctly. Always look where you are going to keep your head in line with the rest of your body.

Achieving balance and harmony with your mule requires more than just balancing and conditioning your mule’s body. As you begin to finish-train your mule, you should shift your awareness more toward your own body. Your mule should already be moving forward fairly steadily and in a longer frame, and basically be obedient to your aids. The objective of finish-training is to build the muscles in your own body, which will cause your aids to become more effective and clearly defined. This involves shedding old habits and building new ones, which takes a lot of time and should not be approached with any impatience. Remember: there are no shortcuts. In order to stabilize your hands and upper body, you need to establish a firm base in your seat and legs. Ideally, you should be able to drop a plumb line from your ear to your shoulder, down through your hips, through your heels and to the ground. To maintain this plumb line, work to make your joints and muscles in your body more supple and flexible by using them correctly. Always look where you are going to keep your head in line with the rest of your body. upper body to the seat and legs, you can do a simple exercise: Put your mule on the rail at an active working walk. On the long side, drop your reins on his neck and feel your lower body connect with his body as you move along. You will need to tip your pelvis forward and stretch your abdominal muscles with each step in order to maintain your shoulder to hip plumb line. If your lower leg remains in the correct position, your thigh muscles will be stretched on the front of your leg from your hip to your knee. There is also a slight side-to-side motion as your mule moves forward that will cause your seat bones to move independently and alternately forward. There is no doubt that you can probably do this fairly easily right from the start, but to maintain this rhythm and body position without thinking about it takes time and repetition.

upper body to the seat and legs, you can do a simple exercise: Put your mule on the rail at an active working walk. On the long side, drop your reins on his neck and feel your lower body connect with his body as you move along. You will need to tip your pelvis forward and stretch your abdominal muscles with each step in order to maintain your shoulder to hip plumb line. If your lower leg remains in the correct position, your thigh muscles will be stretched on the front of your leg from your hip to your knee. There is also a slight side-to-side motion as your mule moves forward that will cause your seat bones to move independently and alternately forward. There is no doubt that you can probably do this fairly easily right from the start, but to maintain this rhythm and body position without thinking about it takes time and repetition. When you and your mule have become adept at the walk and the trot, add the canter. At the canter, however, keep your arms out to the side and rotate them in small backward circles in rhythm with the canter. Be sure to sit back and allow only your pelvis, your seat and your thighs to stretch forward with the canter stride. Keep your upper body erect and your lower leg stable from the knee down. Once your mule has learned to differentiate seat and leg aids in each gait and through the transitions on the large circle, you can begin to work on directional changes through the cones.

When you and your mule have become adept at the walk and the trot, add the canter. At the canter, however, keep your arms out to the side and rotate them in small backward circles in rhythm with the canter. Be sure to sit back and allow only your pelvis, your seat and your thighs to stretch forward with the canter stride. Keep your upper body erect and your lower leg stable from the knee down. Once your mule has learned to differentiate seat and leg aids in each gait and through the transitions on the large circle, you can begin to work on directional changes through the cones.

Training begins with nutrition and the way your equine is fed. An equine that is fed at a specific time each day is far less stressed than those with inconsistent feeding times and will learn easier. What you feed and how is critical. The equine should ALWAYS be asked to stand still with a verbal WHOA and required to remain back when you open a door, or a gate, until they are asked to WALK ON.

Training begins with nutrition and the way your equine is fed. An equine that is fed at a specific time each day is far less stressed than those with inconsistent feeding times and will learn easier. What you feed and how is critical. The equine should ALWAYS be asked to stand still with a verbal WHOA and required to remain back when you open a door, or a gate, until they are asked to WALK ON. The Lucky Three mules willingly come off the grass pasture at any time of the day when they are beckoned. This is the result of routine management, humane training practices, with a prompt and generous reward system. Not one of our equines is herd-bound as we do not play favorites, we reward everyone for good behavior and we do not ask more than they are physically able to give. We have slowly built deep friendships with them that exceed their relationships with their equine buddies!

The Lucky Three mules willingly come off the grass pasture at any time of the day when they are beckoned. This is the result of routine management, humane training practices, with a prompt and generous reward system. Not one of our equines is herd-bound as we do not play favorites, we reward everyone for good behavior and we do not ask more than they are physically able to give. We have slowly built deep friendships with them that exceed their relationships with their equine buddies! We begin training with Leading Exercises in our postural aid we call the Elbow Pull executed in the Hourglass Pattern. The pattern has designated places where they are asked to halt, square up and are given a crimped oats reward. We wait until they finish chewing the oats before we ask for another movement. This will alleviate any anxiety and is their first real introduction to learning how to stand absolutely still upon request. They are grateful for this personal consideration which greatly improves their mental attitude. Each animal is continually assessed throughout training and the approach is modified according to their individual needs. Being fair, respectful, clear and consistent in handling practices with a carefully planned REWARD system –without bribery or indiscriminant treats – will enhance the pleasure and safety that you will experience during interaction with your equine! Anxiety and resistance is always kept to the bare minimum!

We begin training with Leading Exercises in our postural aid we call the Elbow Pull executed in the Hourglass Pattern. The pattern has designated places where they are asked to halt, square up and are given a crimped oats reward. We wait until they finish chewing the oats before we ask for another movement. This will alleviate any anxiety and is their first real introduction to learning how to stand absolutely still upon request. They are grateful for this personal consideration which greatly improves their mental attitude. Each animal is continually assessed throughout training and the approach is modified according to their individual needs. Being fair, respectful, clear and consistent in handling practices with a carefully planned REWARD system –without bribery or indiscriminant treats – will enhance the pleasure and safety that you will experience during interaction with your equine! Anxiety and resistance is always kept to the bare minimum! The next introduction to standing still will take place during their Ground Driving exercises. At first, they will again be driven through the Hourglass Pattern in the Elbow Pull postural aid with the verbal command to WHOA for all the designated halts and squaring up. You will put the lines across their rump, walk to the front, and give them their crimped oats reward. Then resume your position behind them and stand absolutely still while they chew their oats. Only allow them to go forward when you give the verbal command to WALK ON.

The next introduction to standing still will take place during their Ground Driving exercises. At first, they will again be driven through the Hourglass Pattern in the Elbow Pull postural aid with the verbal command to WHOA for all the designated halts and squaring up. You will put the lines across their rump, walk to the front, and give them their crimped oats reward. Then resume your position behind them and stand absolutely still while they chew their oats. Only allow them to go forward when you give the verbal command to WALK ON. with periodic halts, again squaring them up, rewarding and waiting for them to finish chewing before giving the command to WALK ON. Then, repeat the obstacle lessons with strategic halts in the middle of the obstacles while asking them to stand absolutely still. You will eventually be able to phase out the Elbow Pull postural aid.

with periodic halts, again squaring them up, rewarding and waiting for them to finish chewing before giving the command to WALK ON. Then, repeat the obstacle lessons with strategic halts in the middle of the obstacles while asking them to stand absolutely still. You will eventually be able to phase out the Elbow Pull postural aid. Ask your equine to stand quietly while you grasp the saddle at the horn 9Or mane at the withers) and cantle. Put your foot in the stirrup and boost yourself to a standing position at his side. Carefully, lean over his back, talking and petting him until he gets used to your new position. Be sure to reward him from his back on each side.

Ask your equine to stand quietly while you grasp the saddle at the horn 9Or mane at the withers) and cantle. Put your foot in the stirrup and boost yourself to a standing position at his side. Carefully, lean over his back, talking and petting him until he gets used to your new position. Be sure to reward him from his back on each side. Slowly get down, go to the other side and repeat the exercise. Initially, you may mount your mule, or donkey, at the work station. First mount horses in the Round Pen where there is no ceiling overhead. Your goal is to get your equine to be at ease with you putting your foot in the stirrup, and lifting yourself over his back. Get him used to weight in the stirrups, the feel of the saddle and some weight on his back.

Slowly get down, go to the other side and repeat the exercise. Initially, you may mount your mule, or donkey, at the work station. First mount horses in the Round Pen where there is no ceiling overhead. Your goal is to get your equine to be at ease with you putting your foot in the stirrup, and lifting yourself over his back. Get him used to weight in the stirrups, the feel of the saddle and some weight on his back. When he’s calm with this exercise, go to the Round Pen. I prefer to do this preliminary work in an English saddle. It is lighter, easier to handle and less intimidating to the animal.

When he’s calm with this exercise, go to the Round Pen. I prefer to do this preliminary work in an English saddle. It is lighter, easier to handle and less intimidating to the animal. the Round Pen. The stirrups are larger, it’s more stable and the saddle horn might come in handy. Choose the saddle in which you feel most secure.

the Round Pen. The stirrups are larger, it’s more stable and the saddle horn might come in handy. Choose the saddle in which you feel most secure. Your assistant will stand by for safety only and will give the illusion to your animal that he is still just to be lunged, only now with a rider.

Your assistant will stand by for safety only and will give the illusion to your animal that he is still just to be lunged, only now with a rider. rein so you don’t lose him. Have your assistant allow him slack with the line she (or he) is holding. Quietly, and firmly, ask him to “Whoa,” get organized and try it again.

rein so you don’t lose him. Have your assistant allow him slack with the line she (or he) is holding. Quietly, and firmly, ask him to “Whoa,” get organized and try it again. body. Do this on both sides. Add swinging your leg over his back. Stay low with your upper body, leaning forward on both sides. Make him pay attention to you by offering the oats reward from each side.

body. Do this on both sides. Add swinging your leg over his back. Stay low with your upper body, leaning forward on both sides. Make him pay attention to you by offering the oats reward from each side. Rock your weight from side to side and let him feel how the saddle moves on his back. Continually reassure him during this procedure by firmly, but gently, touching him all over his body (See IMPRINTING BEYOND BIRTH under TRAINING/MULE CROSSING on my website at

Rock your weight from side to side and let him feel how the saddle moves on his back. Continually reassure him during this procedure by firmly, but gently, touching him all over his body (See IMPRINTING BEYOND BIRTH under TRAINING/MULE CROSSING on my website at  Do only as much of this in any one lesson as he can easily tolerate. Always try to end your lessons on a positive note, and do not get in too much of a hurry—that’s usually where the trouble begins.

Do only as much of this in any one lesson as he can easily tolerate. Always try to end your lessons on a positive note, and do not get in too much of a hurry—that’s usually where the trouble begins. In order to keep your equine calm, and for the sake of safety, to avoid getting your foot caught in a stirrup and run the risk of having your mule drag you, each time you dismount always take both of your feet out of the stirrups.

In order to keep your equine calm, and for the sake of safety, to avoid getting your foot caught in a stirrup and run the risk of having your mule drag you, each time you dismount always take both of your feet out of the stirrups. By the time your equine is ready for the open arena or the trail, he will clearly know the meaning of WHOA and will learn to be patient and wait for your command to WALK ON. You will be able to halt him at any time with confidence about his absolute obedience. Too many of us get in a hurry to just get on and go.

By the time your equine is ready for the open arena or the trail, he will clearly know the meaning of WHOA and will learn to be patient and wait for your command to WALK ON. You will be able to halt him at any time with confidence about his absolute obedience. Too many of us get in a hurry to just get on and go.

Cindy and I talked about the “Good Old Days” when we used to live on a ranch, had horses and could be gone all day riding with our friends! Today, our lives are so easy and require no experience to have the knowledge that you can now hold in your hand! The value of EXPERIENCE is diminished until you get hurt! There were so many things that we learned by having the full responsibility of cleaning pens, feeding, grooming, tacking up our own horses and then riding in so many different situations. One really LEARNED how to make decisions and analyze the knowledge that we gleaned. We soon learned the approaches and things that we could do SAFELY, and that kept our experiences happy and joyful! We KNEW it would cost a minimum of $5000.00/year to maintain and train our equines! Our relationships with our equines were good and they were able to teach us WELL!

Cindy and I talked about the “Good Old Days” when we used to live on a ranch, had horses and could be gone all day riding with our friends! Today, our lives are so easy and require no experience to have the knowledge that you can now hold in your hand! The value of EXPERIENCE is diminished until you get hurt! There were so many things that we learned by having the full responsibility of cleaning pens, feeding, grooming, tacking up our own horses and then riding in so many different situations. One really LEARNED how to make decisions and analyze the knowledge that we gleaned. We soon learned the approaches and things that we could do SAFELY, and that kept our experiences happy and joyful! We KNEW it would cost a minimum of $5000.00/year to maintain and train our equines! Our relationships with our equines were good and they were able to teach us WELL!

If the last resort is putting them in an auction…BEWARE! You might get stopped with your truck and trailer in the parking lot and a dealer that offers to take them off your hands right there! If you are tight for cash and looking for a convenient fix to your problem, you might think this is a great deal, but this is what KILLER BUYERS do!!!

If the last resort is putting them in an auction…BEWARE! You might get stopped with your truck and trailer in the parking lot and a dealer that offers to take them off your hands right there! If you are tight for cash and looking for a convenient fix to your problem, you might think this is a great deal, but this is what KILLER BUYERS do!!!

jack, and a female horse, called a mare. Mules can either be male or female, but they are unable to reproduce because of an odd number of chromosomes in their genetic makeup. When training mules, one needs to take into account the donkey half of the mule as well as the horse half. Horses can often be trained without the benefit of a personal relationship, but mules are different. The donkey is inherently a warm, affectionate and loving creature that thrives on close relationships with their humans. When this closeness is absent, the donkey or mule can seem stubborn and uncooperative. Thus, there is the old saying, “Stubborn as a mule!”

jack, and a female horse, called a mare. Mules can either be male or female, but they are unable to reproduce because of an odd number of chromosomes in their genetic makeup. When training mules, one needs to take into account the donkey half of the mule as well as the horse half. Horses can often be trained without the benefit of a personal relationship, but mules are different. The donkey is inherently a warm, affectionate and loving creature that thrives on close relationships with their humans. When this closeness is absent, the donkey or mule can seem stubborn and uncooperative. Thus, there is the old saying, “Stubborn as a mule!” enclosure by himself, or just with his dam.

enclosure by himself, or just with his dam. Competition is fun and exciting but can easily become a devastating experience for both of you if the focus is winning against others. Rather, the focus should be to compete against yourself. If you are doing better than the time before, then you are doing well. You don’t need a blue ribbon to mark your improvement. When you go to a show with this attitude, you gain more open communication and friendships with others who have the same interests as you do. You are able to learn from those who are more experienced; judges and officials can help you to improve. This makes the whole showing experience more enjoyable and mutually beneficial to all.

Competition is fun and exciting but can easily become a devastating experience for both of you if the focus is winning against others. Rather, the focus should be to compete against yourself. If you are doing better than the time before, then you are doing well. You don’t need a blue ribbon to mark your improvement. When you go to a show with this attitude, you gain more open communication and friendships with others who have the same interests as you do. You are able to learn from those who are more experienced; judges and officials can help you to improve. This makes the whole showing experience more enjoyable and mutually beneficial to all. Strangely enough, the gate in the trail class just didn’t appear to his mule to be like the gate at home, and the mule would go nowhere near it! He, too, was humbled and left the class with nothing.

Strangely enough, the gate in the trail class just didn’t appear to his mule to be like the gate at home, and the mule would go nowhere near it! He, too, was humbled and left the class with nothing. develop patience and consistency in training, neatness in you and your mule’s appearance, and pride in yourself and your mule.

develop patience and consistency in training, neatness in you and your mule’s appearance, and pride in yourself and your mule. more flies with honey than you can with vinegar.” I used to think in my head, “I don’t really want to catch flies and I don’t even like honey,” but I got her point and she was right. When I got frustrated that my mules were not doing exactly what I wanted them to do, I began to ask myself, “Why not?” I thought I knew everything, until I realized how much I had yet to learn. That is when I stopped trying to force things and became grateful for everything good that happened, every day! People told me that my Longears and my other equines needed a job to be worthy of my respect and support. I thought about it for awhile. Then I realized…my equines never told me they needed a job!

more flies with honey than you can with vinegar.” I used to think in my head, “I don’t really want to catch flies and I don’t even like honey,” but I got her point and she was right. When I got frustrated that my mules were not doing exactly what I wanted them to do, I began to ask myself, “Why not?” I thought I knew everything, until I realized how much I had yet to learn. That is when I stopped trying to force things and became grateful for everything good that happened, every day! People told me that my Longears and my other equines needed a job to be worthy of my respect and support. I thought about it for awhile. Then I realized…my equines never told me they needed a job! the same way toward others? When I opened my heart and my mind to my animals and others…that was when I really discovered how little I knew and how much I had yet to learn. I realized at that time that this would be an endless endeavor, but a lot of time to share and enjoy life!

the same way toward others? When I opened my heart and my mind to my animals and others…that was when I really discovered how little I knew and how much I had yet to learn. I realized at that time that this would be an endless endeavor, but a lot of time to share and enjoy life! what they gave to me…and the gifts they gave just kept coming. They were now true companions, partners, friends and our experiences together were quite literally becoming joyful!

what they gave to me…and the gifts they gave just kept coming. They were now true companions, partners, friends and our experiences together were quite literally becoming joyful! kids was denied. In response to this denial from 4-H Club Leaders, I wrote my book, A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES…for kids and beginners. No longer could the 4-H Leaders use this excuse and mules began cropping up in equine performance throughout the country!

kids was denied. In response to this denial from 4-H Club Leaders, I wrote my book, A GUIDE TO RAISING & SHOWING MULES…for kids and beginners. No longer could the 4-H Leaders use this excuse and mules began cropping up in equine performance throughout the country! entire career, but with my own stubbornness and conviction, I have been able to show folks a better approach.

entire career, but with my own stubbornness and conviction, I have been able to show folks a better approach. Longears have made their way into our society as yet another viable addition for the entertainment of the general population. More people than ever are taking on this challenge and making their mark as Mule Trainers. There is probably nothing as exciting as watching the drivers and their multiple hitches in shows and parades, the least of which is

Longears have made their way into our society as yet another viable addition for the entertainment of the general population. More people than ever are taking on this challenge and making their mark as Mule Trainers. There is probably nothing as exciting as watching the drivers and their multiple hitches in shows and parades, the least of which is  not the 20-Mule Team that is now being exhibited all over America. What a thrill to behold! People are now truly enjoying the affection and companionship these amazing equines have to offer! A light has been shown on the mules of the past! Those that thought mules could not be controlled, are now enjoying the companionship of their own leading celebrities of the equine community! So reject criticism, reject negativity and become a member of this new world of Longears and experience the joy that they have to offer! It’s quite simply…awesome!

not the 20-Mule Team that is now being exhibited all over America. What a thrill to behold! People are now truly enjoying the affection and companionship these amazing equines have to offer! A light has been shown on the mules of the past! Those that thought mules could not be controlled, are now enjoying the companionship of their own leading celebrities of the equine community! So reject criticism, reject negativity and become a member of this new world of Longears and experience the joy that they have to offer! It’s quite simply…awesome!

“Mules separate crude trainers from artistic trainers.” The mule handled by a crude trainer will generally epitomize the traditional belief that mules are stubborn and ornery. The mule handled by an artistic trainer will not.

“Mules separate crude trainers from artistic trainers.” The mule handled by a crude trainer will generally epitomize the traditional belief that mules are stubborn and ornery. The mule handled by an artistic trainer will not.

Horse training trends have evolved from Buck Branaman, Pat Parelli, Clinton Anderson, etc. and their Round Pen training techniques using ropes on the equines. Natural Horsemanship rose from these methods, using less restraint on the equine.

Horse training trends have evolved from Buck Branaman, Pat Parelli, Clinton Anderson, etc. and their Round Pen training techniques using ropes on the equines. Natural Horsemanship rose from these methods, using less restraint on the equine.

This gave way to the new trend of teaching them to lie down. Equines do not lie down easily, so it wasn’t always used as an easy way to mount. It really shouldn’t be used that way because of the added stress put on the equine’s body that can cause arthritis and other problems with the hooves, and joints, as they age.

This gave way to the new trend of teaching them to lie down. Equines do not lie down easily, so it wasn’t always used as an easy way to mount. It really shouldn’t be used that way because of the added stress put on the equine’s body that can cause arthritis and other problems with the hooves, and joints, as they age. I saw a horse being exhibited at the WEG that was forced to bow with ropes. I thought it could be beneficial to find out how long it would take for an equine to learn to bow of his accord with his own muscle strength. Lance learned to do it by himself with only slight encouragement from me in 18 months.

I saw a horse being exhibited at the WEG that was forced to bow with ropes. I thought it could be beneficial to find out how long it would take for an equine to learn to bow of his accord with his own muscle strength. Lance learned to do it by himself with only slight encouragement from me in 18 months. If the argument is that amounting block can’t be brought along for trail riding, it makes more sense to simply acquire a shorter animal.

If the argument is that amounting block can’t be brought along for trail riding, it makes more sense to simply acquire a shorter animal. If you find restraints are not sufficient to help with your equine, you may be dealing with an outlaw, in which case it is best to put him out of his misery before he injures someone. Be careful however about blaming the animal for his response to an inhumane trainer. Some can be rehabilitated, some cannot, but you will need to know what you are doing. Kindness alone is not the answer.

If you find restraints are not sufficient to help with your equine, you may be dealing with an outlaw, in which case it is best to put him out of his misery before he injures someone. Be careful however about blaming the animal for his response to an inhumane trainer. Some can be rehabilitated, some cannot, but you will need to know what you are doing. Kindness alone is not the answer. Today good mule trainers apply the basic techniques of Behavior Modification (reward system training) in their programs. That is, getting the desired response through positive reinforcement and ignoring, as much as possible, the undesired behavior. Negative reinforcement, or punishment, is used sparingly, is never severe and is only used to set boundaries to behavior.

Today good mule trainers apply the basic techniques of Behavior Modification (reward system training) in their programs. That is, getting the desired response through positive reinforcement and ignoring, as much as possible, the undesired behavior. Negative reinforcement, or punishment, is used sparingly, is never severe and is only used to set boundaries to behavior.

By Meredith Hodges

By Meredith Hodges Once the heavier coat is eliminated, a weekly grooming will keep his coat nicely maintained. Daily grooming before a show, or every other day, is even better. Each time you groom him before riding, check and clip as needed the muzzle hairs, around the eyes and ears, and around the coronet bands. Leave the hairs inside the ears to prevent irritation from bugs and flies, but trim the outside edges and backs of the ears. An ounce of corn oil in his feed daily will assure a healthy sheen in his coat on show day without the use of artificial highlighters. Trimming, or shoeing, your mule on a regular six-eight week schedule will assure that his feet will not need attending at the last minute. A routine vaccination, deworming, Coggins testing and a permanent brand inspection will make sure he is ready for transport to any show anywhere at any time. Then, all that remains to be done right before the show is minor clipping, bathing, and polishing hooves.

Once the heavier coat is eliminated, a weekly grooming will keep his coat nicely maintained. Daily grooming before a show, or every other day, is even better. Each time you groom him before riding, check and clip as needed the muzzle hairs, around the eyes and ears, and around the coronet bands. Leave the hairs inside the ears to prevent irritation from bugs and flies, but trim the outside edges and backs of the ears. An ounce of corn oil in his feed daily will assure a healthy sheen in his coat on show day without the use of artificial highlighters. Trimming, or shoeing, your mule on a regular six-eight week schedule will assure that his feet will not need attending at the last minute. A routine vaccination, deworming, Coggins testing and a permanent brand inspection will make sure he is ready for transport to any show anywhere at any time. Then, all that remains to be done right before the show is minor clipping, bathing, and polishing hooves. Then, tack up your animal, checking each piece of equipment to make sure that it is in working order. Go ahead and practice the class. Then, as you unpack your mule, set the tack aside from the rest in your tack room for cleaning later. Do this for each animal in each class. Your animals will do better at the show if they get plenty of rest before the show, so it is wise to spend the day before the show cleaning your tack, clothes, and equipment. Before you begin to clean, load all the items into your trailer that are all ready to go without cleaning. Then, as you clean the remaining items, load them directly into the trailer as you finish them.

Then, tack up your animal, checking each piece of equipment to make sure that it is in working order. Go ahead and practice the class. Then, as you unpack your mule, set the tack aside from the rest in your tack room for cleaning later. Do this for each animal in each class. Your animals will do better at the show if they get plenty of rest before the show, so it is wise to spend the day before the show cleaning your tack, clothes, and equipment. Before you begin to clean, load all the items into your trailer that are all ready to go without cleaning. Then, as you clean the remaining items, load them directly into the trailer as you finish them. can be left until morning, or last minute, provided that you put them in a highly visible spot with a list of what is to be put in attached. Do not try to rely on your memory, as it will be clouded by the excitement and anticipation of the show.

can be left until morning, or last minute, provided that you put them in a highly visible spot with a list of what is to be put in attached. Do not try to rely on your memory, as it will be clouded by the excitement and anticipation of the show. If classes are spaced fairly close together and you are using more than one animal, it is wise to tack up the other animals ahead of time so they are ready to go. If you are using only one saddle for more than one animal, the other animals can still be bridled with the halter slipped over it, so they can be tied and waiting. Be sure to tie up the reins so they will not be chewed or stepped on. If you are using the same mule throughout the show, tacking and stripping should not be too time-consuming if your equipment is well organized.

If classes are spaced fairly close together and you are using more than one animal, it is wise to tack up the other animals ahead of time so they are ready to go. If you are using only one saddle for more than one animal, the other animals can still be bridled with the halter slipped over it, so they can be tied and waiting. Be sure to tie up the reins so they will not be chewed or stepped on. If you are using the same mule throughout the show, tacking and stripping should not be too time-consuming if your equipment is well organized.

Miniature mules and horses settle into their lunging lessons very well, but miniature donkeys (and donkeys in general) really don’t like to be lunged. They just don’t seem to see much purpose in it unless you make it fun for them. If you have a mini donkey, when teaching him to lunge it is helpful if you employ the aid of another type of equine of comparative size (such as a miniature horse or mule) to help “lead” your mini donkey through the lessons. Before I first began lunging my two mini donkeys, Augie and Spuds, I introduced them to Franklin the mini mule, Francis the mini molly mule and Mirage the mini horse by putting them altogether in the larger indoor arena space, and then I put them all in the round pen together. Before I began giving any of them specific instructions, they were all allowed some time to investigate each other and establish their pecking order. Before long all five were lunging cooperatively together, although Spuds did feel the need to kick at Mirage a few times so Mirage would allow him enough space to perform. (Mirage can be a bully sometimes and needed to be put in his place.)