LTR Training Tip #7: Feeding Time – Pasture Grazing

Meredith gets a lot of letters and emails from people with training questions about their equines. Here, she discusses how to best utilize pasture time for a happy and healthy equine.

Meredith gets a lot of letters and emails from people with training questions about their equines. Here, she discusses how to best utilize pasture time for a happy and healthy equine.

Augie and Spuds have been very patient with me for the past year when I did not have time to do anything but grooming once a week and turnout. They were so thrilled to be able to go on another ADVENTURE! Today, we are going to inspect a new project, the false-front town of ASSPEN!

We thought this would be a really nice way to spruce up the big, brown boring wall behind the Lucky Three Eclipse statue and make things even more! Going through the construction zone gives them a chance to practice their good manners and earn their rewards! Although, Spuds is in the lead out of the barn, he prefers it when Augie leads over and through obstacles.

Whatever works best…it’s always negotiable!

“Hey, Augie! What’s this?!”

“I don’t know, Spuds. It looks very interesting though.”

Augie surveys the situation, “Hmmm…a new obstacle course, maybe?!”

“I’m not sure about this, Augie!”

“It’s really easy, Spuds…and kind of fun!”

“Hey, Boys! Welcome to ASSPEN Town!”

“Here’s the Burro Bank, the ASSPEN Sheriff’s Office & Jail, the Chaney Church and the Okie Dokey Undertaker”

“And concrete, Augie!”

“This must be the boardwalk sidewalk, eh Augie?!”

“Yup, but no boards yet! It would be easier with boards!”

“This is the best part, Spuds!”

“You bet! It’s good to be good!”

“And here’s the Half-Ass General Store, L.J.’s Barber Shop and the Crazy Ass Saloon!”

“It’s a little tight going between the boards and the fence, eh, Augie?!”

“No sweat, Spuds! Just pay attention to where you are going!”

“Did she build all this just for US, Augie?!”

“No, Spuds, I think it is for the people that come for tours, but we get to check it out first.”

“Well, it sure makes for a fun obstacle course, Augie!”

“It sure does and it’s great to be able to get out for a walk!”

“Now we have to pose for the camera, Spuds! Try to look nice!”

“Do I really have to?!!!”

“Thanks, Mom! That was fun!!!”

“Yeah, Augie, I like the oats and the ‘snuggles’ afterwards best!”

“I always like our BIG adventures, Spuds!”

“Me, too, Augie!”

To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook, YouTube and Twitter.

© 2016, 2017 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

I hope all of our friends and fans will enjoy yet another translated historical Longears article written by Elke Stadler, originally printed in German in the SWISS BULLETIN that comes to us from Switzerland. More articles to follow!

By Elke Stadler

The French national stud farm had a collection of different documents compiled to determine the profile of mules in ancient times. One particular difficulty was that the historical evidence was all too often misinterpreted. Often the mules were confused with their parents, horse or donkey, or generalized as such. Furthermore, the term “lumenti” (beast of burden) was often used, which was then understood as “mare” or “horse”. Therefore, a large quantity of historical, iconographic and archaeological data had to be examined in order can clearly define the physical characteristics.

Historical sources

The agricultural and veterinary studies of the ancient authors, from Columella, Pliny, Palladius to Vegetus, show how accurate the knowledge of the mule was, from breeding to handling, and they highlight all its advantages. Historians like Suetonius, the Roman poet Martial or the Greek Aesop show the widespread use of the mule in their fables.

Iconographic sources

Iconography (the science of the interpretation of motives in works of art) has collected numerous proofs of the existence of mules since the earliest antiquity. These are engravings, drawings, illustrations on vessels, reliefs and figures, which can be seen on buildings and monuments in various countries or are exhibited in museums. Bones and teeth have been found and analyzed during excavations. Some of the interesting mule representations and archaeological finds are presented here:

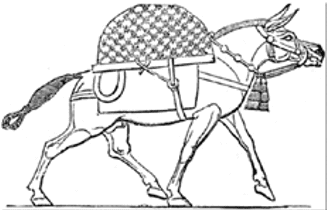

A depiction of an engraved mule from the Assyrian period shows that mules already wore richly decorated harness with metal or textile ornaments (pompons) in this period. (in: John Clark Ridpath Cyclopedia of Universal History Cincinnati: The Jones Brothers Publishing CO., 1885).

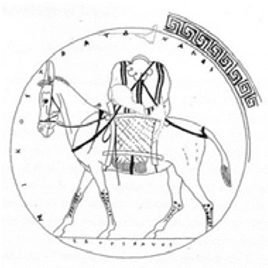

Picture on a vase with red figures representing a loaded mule. (in: P. Hartwig, Die griechischen Meisterschalen, Berlin 1883, p. 63).

Drawings that clearly show the basic equipment of a mule with military equipment: Baskets on both sides to balance the weight (the basket is deliberately drawn flatter and wider to make the contents visible) and the bridle to guide the mule.

Ladies riding mules. Greek-Persian relief, Erdemli Yörük Museum, Province Mersin, Turkey.

Mule with amphorae. Clay figures from Cyprus, from the time of the Hellenic kingdoms, around the 3rd and 2nd century BC, in the Louvre, Paris.

Mule with handmade saddle. A broken bronze votive plaque found at the height of the Gotthard pass. Archaeological Museum Bavay, France.

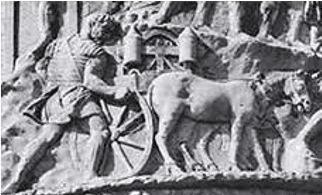

A cart pulled by mules. Scene on the Trajan Column, Relief, Archaeological Museum Strasbourg.

An honorary column erected in 112/113 AD for the Roman Emperor Trajan (98-117 AD) at his hometown Rome.

Light two-wheeled cart (open wagon for short distances) pulled by two mules. Relief picture on the reconstructed and colored “Igeler Säule”, UNESCO World Heritage Site. Tomb monument of a rich cloth merchant family, which is in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier, Germany.

Rhyton, single-cornered drinking vessel for drinking sacrifices. Red ceramic figure, ca. 475-450 BC. Pre-Roman necropolis from Casabianda, Corsica. Archaeological museum of the department of Gilort (Jérôme) Carcopino.

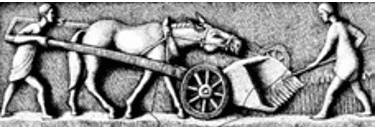

Operation of the famous harvesting machine known as the “Trevires” or “Vallus” harvester, described in particular by Plinius. Facsimile of a fragmentary relief found in Buzenol, Belgium.

Drawing that brings together two different fragments from the collections of Arlon and Buzenol, showing the farm workers and the mule harvesting spelt with the harvesting machine.

Some numismatic finds: the mule is depicted on many Roman coins, often pulling a two-wheeled carriage (Carpentum). Below: grazing mules, behind them the two shafts of a wagon with reins.

Source:

We hope you enjoy Part 2 of the translated historical Longears article written by Elke Stadler, originally printed in German in the SWISS BULLETIN that comes to us from Switzerland. More articles to follow!

By Elke Stadler

Further evidence of mules in ancient times is shown by finds from various archaeological excavations. The identification of hybrids is more and more illuminated by archaeological research. The finds of mule bones on civil and military sites are scattered throughout Europe.

In Pompeii

Pompeii was an ancient city located in the modern commune of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pompeii

In the stable of the house of “Casa Amanti” the remains of equine skeletons were found, five in total, including four donkeys between 4 and 9 years old and one male mule between 8 and 9 years old. The equines were probably used as pack animals for the transport of pastries. An analysis of the food remains in the stable was also taken.

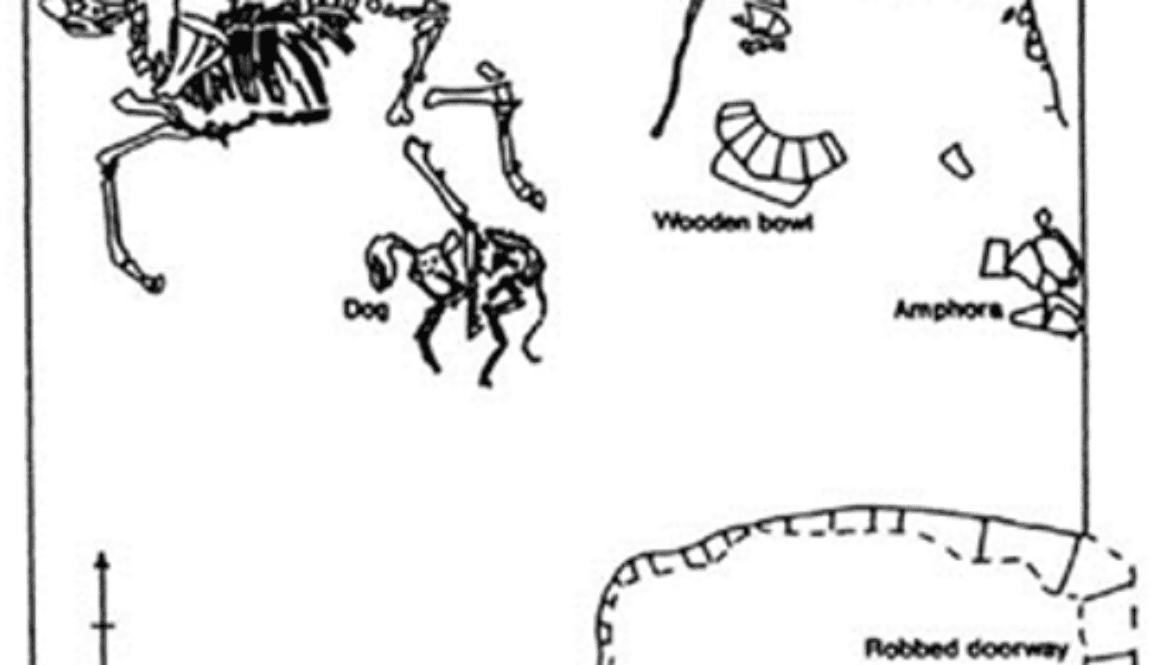

Left: Plan of a horse stable in Pompei, Anthopozoologica 31,2000, pp. 119-123.

Right: Pompeii, Casa Amanti, houses 6 and 7, Insula 12, region IX, Genovese A, Cocca T.

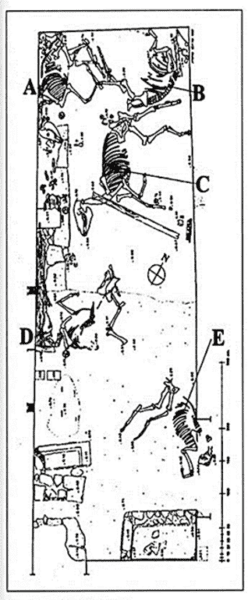

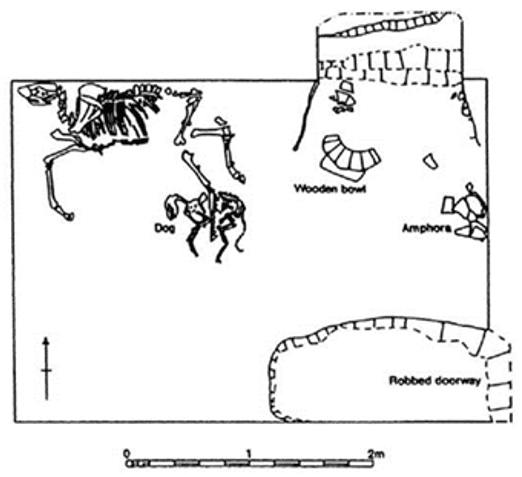

Pompeii, Insula 9, house 12, room 4, region I, (casa amarantus)

(Berry J., The conditions of domestic life in pompii in AD 79: A case study of houses 11 and 12, insula 9, region I, Papers of the British School at Rome)

In the stable on this area, probably originally a “Kubikulum” (side room), the skeletons of a mule and a dog were found. On the northern wall, remains of wood can be seen, which indicate a feeding rack. The palynological examination of the plant remains showed a variety of grasses and weeds as well as cereals, olives and nuts, indicating forage, litter and dung. Two fortified iron rings near the mule’s head suggest that it was tied up at the time of death.

The large number of amphorae in the “Impluvium” (water collection basin) of the nearby atrium (Roman dwelling house), as well as the remains of a broken amphora in the stable, indicate that the mule was intended to transport amphorae to the city. The remains of a dilapidated “Caupona” (bar, sales room) in the adjacent Insula 11 indicate commercial activity. An inscription on the western front (AMARANTUS POMPEIANUS ROG (AT) and three painted inscriptions, one on the neck (EX POMPEI AMARANTI) and two on the belly of several amphorae found in the building, indicate that Amarantus was a wine merchant, which required the keeping of a mule to transport the amphorae.

Great Britain, London

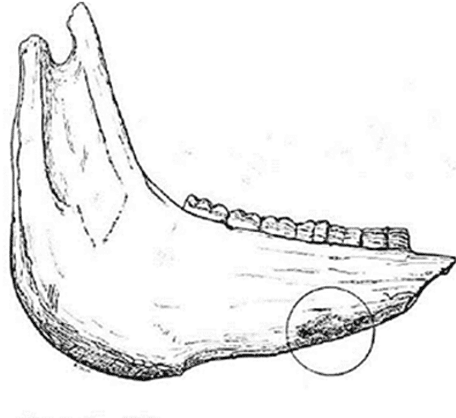

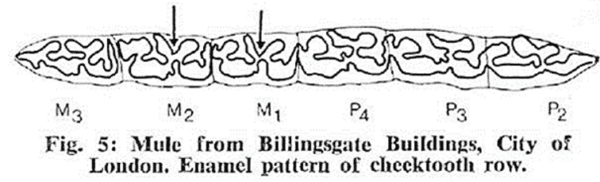

The mule jaw was found in a landfill. It dates from the Roman period (period II, phase 3) around 125-160 A.D. Age at death of the animal: more than 5 years, perhaps between 11 and 14 years.

The age determination is inaccurate, as the jaw is broken at the level of the incisors. The age can only be determined more accurately on the basis of the wear and tear of the incisors. It was also not possible to determine the sex because of the missing canines, the sex index. They are more developed in males than in females. The pronounced wear in an area of the jawbone (circle) is probably the result of the damaging pressure from a halter or muzzle.

Examination of the molar profile of the jaw made it possible to determine the London jaw more reliably than mule jaws. It has a very accentuated “V” shape of the lateral cavities of the first molars (cheek teeth). The comparison with the lower jaw of another mule (Dangstetten) shows a strong similarity.

According to Armitage P, Chapman C, Roman Mules, The London Archaeologist, 3/13,1979, S. 339-359)

Kalkriese, Niedersachsen, Germany

The finding region Kalkriese is an area in northwest of Germany, where large quantities of Roman archaeological finds were made. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalkriese

Archaeologists have identified the bones of eight horses and about thirty mules on the site of the Battle of Kalkriese, which took place in 9 A.D., including two skeletons in good condition at the trenches dug by the Germans to capture the Roman vanguard. The first mule was found in the trench, its bones (head, neck and shoulders) and its harnesses are in adequate position. The animal was therefore not completely exposed to natural decay (which explains the good osteological and anatomical preservation conditions).

The mule had an iron bridle and harness with metal elements and stones, and a bronze bell with iron clapper. The inside of the bell was stuffed with oat straw wrapped around the clapper so that the bells were not heard in enemy territory. The growth of the roots on the stems indicated late summer – early autumn, which made it possible to determine the date of the ambush around September.

In 1999 the fragmentary remains of a second 4-year-old mule were found. It carried a smaller bronze bell and an iron bridle. The animal died of a broken neck, probably while trying to climb the German wall in the general panic of the fight.

According to: Rost A, Wilbers -Rost S; Waffen auf dem Schlachtfeld von Kalkriese, Gladius XXX; 2010, pp. 117-135 and Harnecker J, Franzius G, Kalkriese 4th Catalogue of Roman Finds from the Oberesch. Die Schnitte 1 bis 22; Römisch-Germanische Forschungen vol. 66. 2008 and Wells P.S., Die Schlacht, die Rom stoppte, Kaiser Augustus, Arminius und das Abschlachten der Legionen im Teutoburger Wald, 2003)

Carnuntum, Austria

It is the most important and most extensively researched ancient excavation site in Austria 28 mi east of Vienna. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carnuntum

Horses and mule bones were discovered in the outer ditch and in pits on the edge of the first ditch of this Roman legionary camp. Four mules could be identified from the remains. The sex could be determined based on the development of the canines on the lower jaws. They were only male animals. Two of them died at the age of 6-7 years, the other two at about 15-17 years. The age is estimated on the basis of the abrasion of the teeth. Since mule teeth are harder than those of horses, the age had been underestimated and had to be reassessed.

The height at the withers was determined in relation to the length of the bones found. It was approximately between not less than 140 cm and maximum 155 cm. Apart from one mule, the other three suffered from diseases of the limbs and/or the spine caused by frequent heavy loading. A pathological change in the spinal column of a mule also indicates this. One shows a pathology (exostosis) on the jaw, which is caused by repeated rubbing of a bit or harness.

According to: Kunst G. K., Archäozoologischer Nachweis für Equidengebrauch, Geschlechtsstruktur und Mortalität in einem neuartigen Hilfskastell (Carnuntum-Petronell, Niederösterreich), Anthropozoologica 31; Ibex J. Mt. Ecol 5.2000

Weissenburg, Bavaria, Germany, Biriciana Roman Fort

The Roman fort at Weissenburg, called Biriciana in ancient times, is a former Roman Ala castellum, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located near the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biriciana

The Roman fort at Weissenburg, called Biriciana in ancient times, is a former Roman Ala castellum, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located near the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biriciana

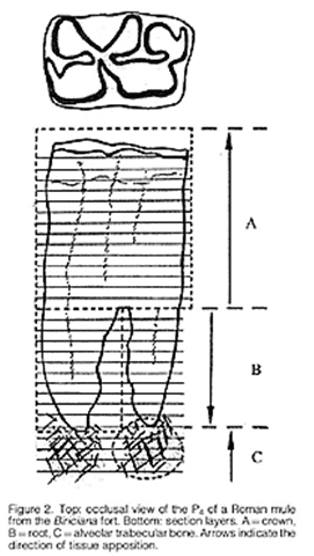

Four skeletal remains of mules were found during an excavation in this Roman camp. The age was determined to be 160 AD after the discovery of eleven coins. They were found in a bag that was left with the mules. The authors raise the question of a possible local breeding or traditional import of mules from Mediterranean countries. When examining the teeth of an 8-year-old mule, it was found that the food in the mule’s environment must have changed until the time of its death. The animal spent part of its life at high altitude, according to the proximity of the camp, probably in the Alps. The investigations show that the animal must have been born and bred in northern Italy. It must have been used for work in the Alps for a while and later on until the end of its life near Fort Weissenburg.

According to Berger T. E., Peters J., Grupe G. Life history of a mule (ca. 160 AD) from the Roman fort Biriciana/Weissenburg (Upper Bavaria), as revealed by serial stable isotope analysis of dental tissue, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Volume 20, Issue 2, March/April 2010, pp. 158-171.

Further Sources: https://leg8.fr/armee-romaine/mulet-du-ier-siecle-qui-es-tu