Sybil Ludington: The Female Paul Revere

This article is a repost of Valerie DeBenedette‘s article at Mental Floss.

“… the midnight ride of Paul Revere, On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five: Hardly a man is now alive …”

Yes, the famed Paul Revere set out on horseback on this day in 1775 to raise the alarm that British troops were on their way from Boston to Lexington.

Revere rode about 20 miles through what is now Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Massachusetts, knocking on doors to raise people to defend Lexington. Another rider, William Dawes, was sent by another route to do the same thing. A third, Samuel Prescott, was also pressed into service. Only Prescott completed the night’s work and reached Concord; Revere was captured and Dawes was thrown from his horse while evading British soldiers, forcing him to walk back to Lexington.

Revere rode about 20 miles through what is now Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Massachusetts, knocking on doors to raise people to defend Lexington. Another rider, William Dawes, was sent by another route to do the same thing. A third, Samuel Prescott, was also pressed into service. Only Prescott completed the night’s work and reached Concord; Revere was captured and Dawes was thrown from his horse while evading British soldiers, forcing him to walk back to Lexington.

It was a good ride for Revere, and it was good for the revolution. But a little over two years later, a 16-year-old girl did the midnight riders one better. Sybil Ludington rode twice as far as Revere did, by herself, over bad roads, and in an area roamed by outlaws, to raise Patriot troops to fight in the Battle of Danbury and the Battle of Ridgefield in Connecticut. And did we mention it was raining?

Sybil was the eldest of 12 children of Col. Henry Ludington, the commander of the militia in Dutchess County, New York. Ludington’s farm was a receiving center for information collected by spies for the American cause.

In April 1777, Colonel Ludington and the members of his militia were at their homes because it was planting season. But about 9 p.m. on the evening of April 26, he received word that the British were burning Danbury. The man who brought the news had worn out his horse and he didn’t know the area. Ludington needed to stay where he was to help arrange the troops as they arrived.

Who could he send? He turned to his daughter, who knew the area and knew where members of the militia lived. Sybil rode her horse from her father’s farm in Kent, which was then called Frederick. She first headed south to the village of Carmel and then down to Mahopac. She turned west to Mahopac Falls and then north to Kent Cliffs and Farmers Mills. From there, she rode further north to Stormville, where she turned south to head back to her family’s farm. All told, she rode nearly 40 miles through what was then southern Dutchess County (which is now mostly Putnam County).

Sybil spent the night traveling down narrow dirt roads in the rain with nothing but a stick as protection. To add another element of danger, there were many British loyalists in the area and more than a few “Skinners,” a word generally used then to describe an outlaw or ruffian who had no real loyalties to either side in the war. One account of her ride says that Sybil used her stick to pound on a Skinner who accosted her.

Sybil spent the night traveling down narrow dirt roads in the rain with nothing but a stick as protection. To add another element of danger, there were many British loyalists in the area and more than a few “Skinners,” a word generally used then to describe an outlaw or ruffian who had no real loyalties to either side in the war. One account of her ride says that Sybil used her stick to pound on a Skinner who accosted her.

By dawn, Sybil had made it back to her family farm where the militia men were gathering with her father. By this time, the British had gone south from Danbury to Ridgefield. The militia of Dutchess County, led by Colonel Ludington, marched 17 miles to Ridgefield and took part in the battle there, which some considered a strategic victory for the American forces.

Sybil’s hard riding earned her the congratulations of General George Washington, but it seems she got little recognition for her feat after that. She married another revolutionary, Edmond Ogden, in 1784 and had a child. At one point she and her husband ran a tavern in Catskill, New York, but she spent the last 40 years of her life as a widow until her death in 1839. She is buried near the route of her ride in Patterson, New York, with a headstone that spells her first name as Sibbell.

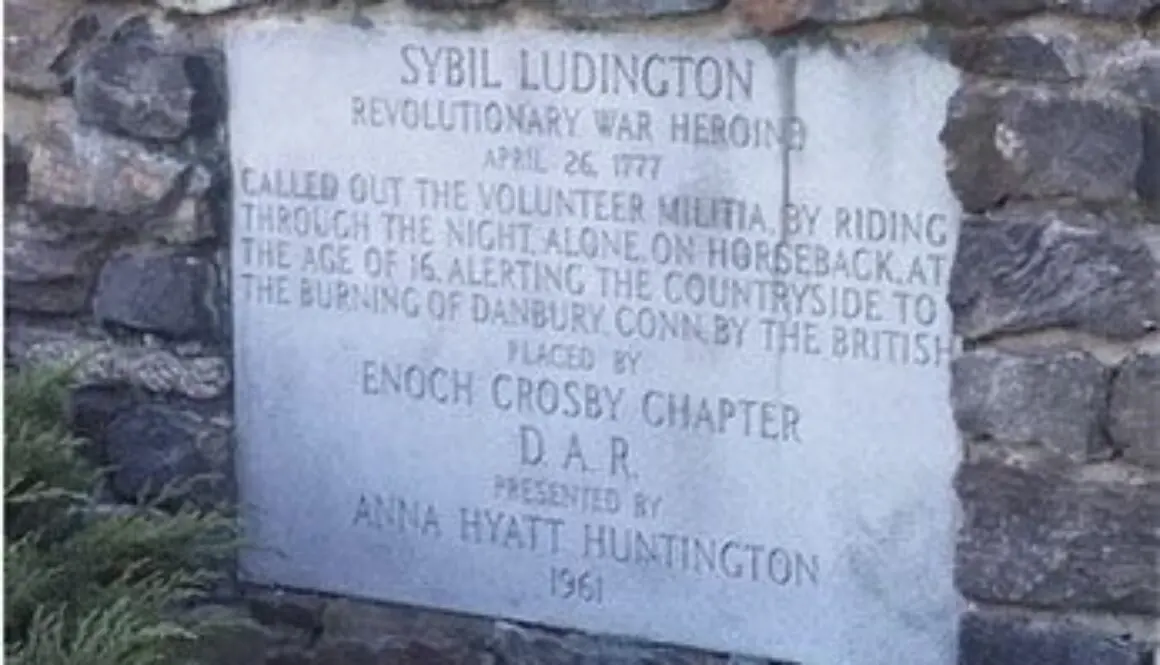

So why do we all learn about Paul Revere in our American history courses and not Sybil Ludington? In more recent times, Sybil has received a bit more acclaim for the ride that she made—there have been books written about her, a postage stamp near the bicentennial honoring her, and even a board game where players follow her overnight path. And in 1961, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a larger-than-life statue of her on her horse in Carmel, New York.

Revere, of course, is justly honored as a man who served the Revolution in many capacities, including as a messenger and engraver (by trade, he was a fine silversmith). Perhaps his place in history was secured because he had Henry Wadsworth Longfellow serving as his publicist, with Longfellow’s famous (and famously inaccurate) poem—it leaves out both Dawes and Prescott—turning Revere into a legend. Sybil has no such fabled poem, no “one if by land, two if by sea” catchphrase. But perhaps as children we all should hear of the midnight ride of a teen with no fear.

All images courtesy Valerie DeBenedette.